I’m always on the lookout for people who can hold diametrically opposed views in their head simultaneously. Is that why I enjoy Claire Danes in Homeland so much?[1]

I’m always on the lookout for people who can hold diametrically opposed views in their head simultaneously. Is that why I enjoy Claire Danes in Homeland so much?[1]

Gary Sernovitz, the author of The Green and the Black, brings the perfect profile for diametrically opposed thoughts about the fracking boom, which is probably what we need to explore the oil and gas revolution of the past decade. He’s a self-described New York liberal, who works as a managing director of a private equity firm focused on oil and gas.

He’s deeply immersed in industry research, and he’s a good writer with a sly sense of humor.

He covers the environmental impact, financial impact, and the geopolitical impact of the shale revolution. He also clearly appreciates the capitalists at the core of the story, although often humorously for their mistakes and faults as much as for their tremendous success.

Environmental Impact

Since any conversation about fracking inevitably leads to an environmental fight, its worth noting Sernovitz quickly distances himself from a hardcore industry perspective.

“I believe the scientific consensus that climate change is happening now because of fossil fuels. The evidence for yet more changes is overwhelming. Climate change is a serious threat to human life. While I am more hopeful than most environmentalists that we can address these issues with technology, efficiency gains, and a cleaner energy mix, I believe that continuing to consume energy as we do will have terrifying effects over the coming decades.”

One central point of Sernovitz’ book, however, is that the environmental narrative of the fracking boom isn’t as simple as it’s frequently portrayed. Neither from the opponents’ side, such as was presented in the anti-fracking documentary Gasland, nor from proponents’ side, from industry.

It’s safe to say that each side of that debate considers the other side to be morons, which is never a great place to begin a discussion. Sernovitz is neither a moron nor an ideologue. Rather, he is someone who, while profiting from the oil and gas business and fracking in particular, has spent a tremendous amount of time thinking about opponents’ views.

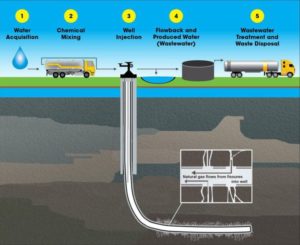

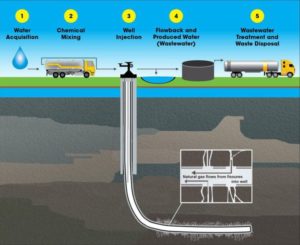

To Sernovitz’ credit, he dedicates 49 pages to what he calls “The Local Perspective,” by which he means what an economist might call the environmental externalities of fracking. The open frack-water ponds, the worries about local drinking water, the possibility of leakage, the earthquakes.[2] Gasland, he argues, presented a simplified, non-scientific and non-representative propaganda piece about dangers to the drinking water, which is probably not the real big local environmental impact of fracking anyway.

He also dedicates 34 pages to what he calls “The Global Perspective” on fracking, which he short-hands as the “the Al Gore” worry, that the boom in cheap non-renewable hydrocarbons dooms us to a warmed planet and apocalyptic results. To his credit – and in line with my own fears about the biggest environmental impact of fracking – Sernovitz allows that he worries about this too. Our short-term pleasure at being able to drive huge SUVs at affordable pump-prices will be punished by the long-term irreversible damage we do to all living things by not switching to renewable, non-polluting energy sources, and possibly quite soon.

Sernovitz’ articulated environmental hope, and one senses that he’s explored this angle deeply with concerned liberal foundation boards who want to invest with his company but also prefer not to wreck the planet, is that the ‘clean gas’ boom will be an intermediate weaning step away from dirty coal and onto the energy renewables in the future.

But he’s not such an ideologue that he’s sure:

- this will happen; or

- That the methane emissions from gas extraction wont prove, in the long run, as deadly to the planet as coal’s CO2 impact.

He concludes that we just don’t know enough yet about the methane problem to measure it against other alternatives. Meanwhile he holds out hope that gas isn’t all bad, when compared to its current alternative, coal.

Capitalist fun

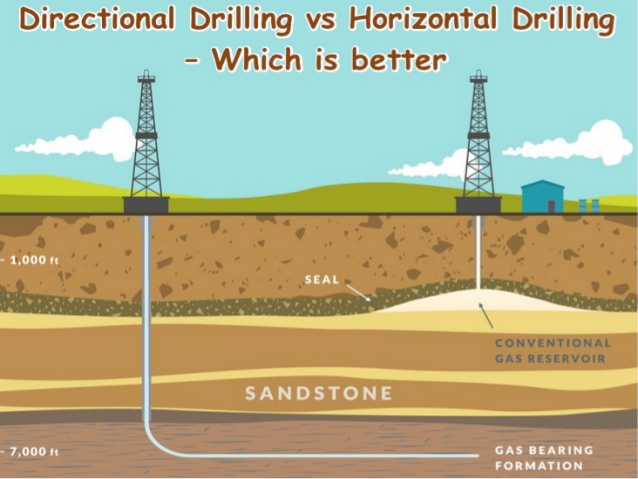

Sernovitz clearly enjoys the story of capitalism working – innovation, mistakes, risk-taking, salesmanship, fortunes lost, fortunes won, and surprising global changes wrought, where they were least expected. He admires the pioneering spirit and grit that the early frackers showed. Elements of fracking techniques, including horizontal drilling and using liquids to open up closed shale rock, had existed for decades. But as Sernovitz explains, the right combination of techniques required much trial and error.

One story of The Green and the Black is how this combination of innovations and elimination of errors transformed the US from a forgotten has-been producer of expensive oil and gas into a leading supplier and global driver of far-cheaper oil and gas.

Sernovitz does not settle for the convenient anointing of far-seeing geniuses that many business books do. Instead, he acknowledges the role of extraordinary luck, as well as a we-had-no-choice-with-our-backs-up-against-the-wall decision-making of the fracking giants Aubrey McLendon, Mark Papa, Harold Hamm, and George Mitchell – who he anoints the four members of the Mount Rushmore of Fracking.

How financially valuable?

Sernovitz tries some back-of-the-envelope calculations of the income and wealth effects of the US fracking boom. Between 2007 and 2014, he estimates, the oil and gas industry netted $150 billion in additional income due to the shale revolution. More substantially, however, is the future wealth effect of making shale deposits a viable source of oil and gas. Between usable and estimated reserves, plus ancillary investments in pipelines, gathering systems, and export terminals, the wealth effect of the fracking boom probably adds up to $2 Trillion, according to Sernovitz. Which is quite a lot.

Other facts about the fracking boom also offer a sense of scale, such as the weird one that the size of the Bakken shale in North Dakota would give – at $60 per barrel of oil – a theoretical Nation of North Dakota a per capital oil wealth between four and five times bigger than Saudi Arabia. Whoa.

In my one-time adopted state of New York, where fracking was subject to a moratorium since 2008 and effectively banned since 2015, the technique and subsequent energy boom is a kind of shorthand for capitalist evil.

Where I currently live in South Texas, fracking may not be universally celebrated but even people who did not get rich from the recent boom have a sense that it has meant a huge economic shot in the arm for the region. Criticism tends to be muted, and, politically at least, a non-issue. People don’t need to shout “Drill, Baby, Drill” in South Texas because that’s going to happen anyway and it’s in fact against state law for municipal entities to restrict it. There’s no reason to shout about an activity that the entire political structure supports.

Geopolitcs

Sernovitz would like the layperson to understand not just the financial implications of the shale boom, but also the potential geopolitical changes wrought.

Here Sernovitz strikes a mostly optimistic note. Reduced dependence on frenemies like Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, and independence from more traditional enemies or rivals like Iran and Russia, he argues, makes the shale revolution a geopolitical gamechanger for the United States.

We will have less need to prop up kleptocracies or become partisans in places like South Sudan or Libya if we’ve got options, at a reasonable price, under our own land. This won’t stop the sea from rising and swamping our coastal cities, of course, but it is one less thing to disrupt the world.

Absence of traditional blame narrative

Have you ever had a conversation with a sub-prime mortgage CDO structurer about what he thought he was doing before 2007, creating a weapon of mass financial destruction? No? If you did, you’d understand the story is a bit more complex than the journalistic narrative. The products were not designed to be as toxic as they seemed, in retrospect. For reals, and I’m not being smirky as I write this, the underlying products were designed so that people with an imperfect credit history could buy a house. That was the real product, which we seem to forget. People in the sub-prime mortgage CDO production chain all had their own narrow self-interested job to do, but the underlying idea was not evil at all.

In that spirit, I appreciate Sernovitz’s frustration:

“It sometimes seems as if environmentalists believe that the oil industry’s business is to make carbon dioxide. Our business is to make fuel. Carbon dioxide is the by-product, the vast majority of which is emitted when people consume our products – in ‘your’ wheels, not ‘ours.’”

And then he continues,

“Yes, I believe that there is a moral difference between making money by producing oil and spending money by consuming it. I do not dispute that climate change is more on my conscience that on others.’ But that moral difference is subtle, subjective…”

I also appreciate Sernovitz’ position as a New Yorker surrounded by people who casually hate his industry. He does not have the luxury of unreflective one-sidedness. On the contrary, he is an expert ambassador for the industry living deep in enemy territory.

One of the problems with forming unbiased opinions on complex business topics is that true experts tend to come from within their own industry. And in that sense, may be discounted by critics as self-interested in defending the industry. But if you don’t listen to experts from the industry, you’re probably not listening to the most important experts on the situation.

Of course, at the end, I’m jealous of Sernovitz too.

He writes humorously and from a position of deep knowledge about an important finance topic. He writes about the big picture, as well as the minutia of his industry. He continues to make money with his expertise. Did I mention he’s funny as well?

Basically, I hate him.

Maybe I’ll get up the guts to ask him to do a podcast here.

Please see related posts:

All Bankers Anonymous Book Reviews In One Place

[1] Is that why I’m still a Catholic despite the ridiculous medieval bent to the Church’s teachings?

[2] Since I finished the book a week ago, earthquakes in Oklahoma have put the “seismic activity” problem of frack-water disposal back on the front burner. Ugh.

Post read (433) times.