Texas State Senator Paul Bettencourt, (R-Houston) poked the bear when he filed Senate Bills 1750 and 1751, which would allow the Teachers Retirement System of Texas (TRS) and Employee Retirement System of Texas (ERS) to study, and possibly implement, changes in their public pensions. Change would mean moving – in an as-yet unspecified way – from a traditional “defined benefit” to a more 401K-style “defined contribution” plan. The effect would be to shift the burden of paying for retirement, somewhat, from taxpayers to employees. The bills as written specifically would only affect newly hired employees, not existing employees or retirees.

Texas State Senator Paul Bettencourt, (R-Houston) poked the bear when he filed Senate Bills 1750 and 1751, which would allow the Teachers Retirement System of Texas (TRS) and Employee Retirement System of Texas (ERS) to study, and possibly implement, changes in their public pensions. Change would mean moving – in an as-yet unspecified way – from a traditional “defined benefit” to a more 401K-style “defined contribution” plan. The effect would be to shift the burden of paying for retirement, somewhat, from taxpayers to employees. The bills as written specifically would only affect newly hired employees, not existing employees or retirees.

The bear he poked, of course, is public school teachers.

Public school teachers in Texas face steeper challenges planning their retirement than other professionals, in part because the vast majority cannot participate in Social Security, in part because of modest pay increases throughout a full career of service, and in part due to barriers to good retirement advice.

I don’t blame teachers, their union, and groups like the Texas Public Employees Association and Texas Retired Teachers Association (TRTA) that have come out in opposition to the bills. Tim Lee, Executive Director of TRTA, told me that an estimated 120 thousand text messages had been sent to legislators regarding changes toward a hybrid plan, such as suggested in SB 1751. Lee regards a shift to a hybrid system – even for only new hires – as undermining the strength of the entire TRS. A change caused by these bills would cause his organization to rethink their strategic approach to everything, including whether to advocate for joining the Social Security system. They don’t currently, but might in the future if they thought a hybrid system weakened TRS.

And yet, (and here’s where I become a target for the next 10,000 angry text messages from teachers) Bettencourt has an important point to make, by filing these bills. “Long term, what I hope to do is start a discussion about the real cost of pensions,” Bettencourt told me.

As a finance guy, I want my public officials staying up late worried about public pensions, seeking ways to reduce their systemic risks. TRS has more than 1.5 million members, more than $130 billion in net assets, and represents the ultimate “Too Big To Fail” public pension in Texas.

As a finance guy, I want my public officials staying up late worried about public pensions, seeking ways to reduce their systemic risks. TRS has more than 1.5 million members, more than $130 billion in net assets, and represents the ultimate “Too Big To Fail” public pension in Texas.

Reasonable people can disagree on the following, but on the four biggest measurements of a pension plan’s health, the TRS according to its 2016 audit is worse off than we’d wish for, although maybe still within acceptable bounds.

- We want at least an 80 percent “Funded Ratio” – the percent of money owed to pensioners that’s covered by money already in the investment portfolio. TRS is now at 79.7 percent. Too low.

- We want less than 30 years to “amortize” or pay down, pension debts, and would prefer 15 to 20 years. TRS is at 33 years. Too long.

- We would prefer a low, or conservative, annual return assumption, compared to a national average of 7.47 percent annual return assumption in pension plans. The TRS assumes an optimistic 8 percent return. Too high.

- Finally, the unfunded liability part of the pension – money owed to retirees but not yet paid for – has grown from zero in the year 2000 to approximately $35 billion this year. Too big.

None is this spells catastrophe today, in my view. It just means the TRS is not, currently, building in room for error. As a teacher, if TRS is my main safety net, these numbers do not make me comfortable.

Actually, let me restate: Were I a young teacher, or a prospective teacher facing a new career, I would be livid about those TRS numbers. Older teachers – those close to retirement or already retired – are probably fine, and realistically won’t get benefits chopped to make up any future shortfalls. Rule changes in pensions always hurt the young ones.

In fact, one of the main flaws of the TRS design is this “generational inequity” in favor of older teachers rather than younger teachers, according to Josh McGee, who is both a pension-plan economist for the John Arnold Foundation and the Chairman of the Texas Pension Review Board. McGee has written extensively about how traditional pensions like TRS strongly favor veterans over younger teachers, especially those who change jobs or leave the system at any point in their career.

Defined benefit plans are most generous to veterans of over 20 years, but McGee cites figures that only 28 percent of teachers nationwide stay for that long. The early-departing teachers lose many of their hard-earned retirement rewards.

A defined contribution plan or hybrid plan theoretically could allow teachers the chance to self-fund part of their retirement, which could accompany them to another career or another location.

Then there’s the issue of pension plan solvency.

“When you look around the state, the Dallas [Police and Fire] Pension is a smoking crater at this point in time. Houston is not far behind,” Senator Bettencourt notes, referencing existing problems in public employee pensions in the state’s largest municipalities.

The following are my words, not Sen. Bettencourt’s, but I regard public pension plans as ticking time bombs. Not because the managers of TRS are bad, or because anyone is doing anything particularly wrong. It’s just that small decisions to underfund a public pension can, over decades, compound into giant problems. Make a few wrong assumptions – the 8 percent return assumption seems way high to me for example – and you end up with a big fiscal hole in the state.

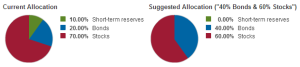

A safer approach for teachers and taxpayers might in fact be to shift, over time, some of the risks away from taxpayers. Currently 13 states have a version of a hybrid system of the type that Bettencourt’s bill would allow, while 38 states continue with a “defined benefit” plan like Texas’ current TRS.

It’s a debate worth having now, before anything bad happens.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and the Houston Chronicle.

Please see related post:

Teachers and the struggle to get good financial advice

Interview with Mint: I give ALL the answers

Post read (805) times.