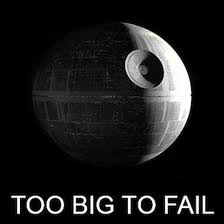

I frequently complain in this space about the Too Big To Fail (TBTF) banks in the wake of the 2008 Crisis. For me, TBTF is short-hand for the idea that large, private, for-profit enterprises – and by extension their employees and investors – enjoy an implicit government guaranty in the event of financial calamity. While small or medium sized financial institutions (or non-financial institutions) may and do regularly fail, certain companies cannot, by dint of their size and systemic importance.

As a result of the real and implied government guaranty, we widely acknowledge the risk of ‘moral hazard,’ in which executives, employees, and investors take greater risks than would otherwise be prudent, knowing there’s an invisible safety net below their high-wire activities.

The largest banks perhaps always had this implied government guaranty, although it had not really been tested until the 2008 crisis, so it was an idea talked about, in terms of moral hazard, but not necessarily believed in.

With the emergency investment of Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) funds in October 2008 into 12 systemically important financial institutions – combined with the concurrent receivership of mortgage insurers Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac, nearly unlimited liquidity provisions to AIG, and non-recourse liquidity by the US Treasury and the Federal Reserve to JP Morgan Chase and Bank of America to acquire the ailing Bear Stearns and Merrill Lynch respectively – we suddenly found out just who was TBTF and to what extent all taxpayers would have to backstop private firms, in order to ensure the financial system’s survival.

Given all of this, I have been naturally curious to read Goldman Sachs’ May 2013 research paper “Measuring The TBTF Effect on Bond Pricing.” ** I finally got around to it this week.

I enjoyed the piece and it has its strengths, which I’ll describe below. Unfortunately, the paper is also a great example of how asking the wrong set of questions allows you to completely miss the relevant point.

The TBTF GS research paper

Goldman concludes that the advantage of being TBTF is limited, mixed, and inconclusive.

In short, large banks as a group enjoyed some small advantage before the crisis, a marked clear advantage in the years 2011 and 2012, and some apparent disadvantage in 2013.

Their analysis focuses on the differential in funding costs – technically ‘yield spread’ but to keep this simple let’s say funding costs – that the biggest banks enjoy, when compared to smaller banks.

If you can fund your business more cheaply, it stands to reason that you can make more money. What their research says is that the largest banks as a group had a slight money-making advantage pre-crisis, a definite advantage during the crisis, and some measurable disadvantage now.

Unlike many who instinctively mistrust Wall Street – and in particular Goldman, the firm that weathered the financial storm the best – I expected Goldman’s research to not be derisible as entirely self-serving. And I was right. This is serious, albeit dry, analysis.

The most useful part – pointing out where others went wrong

The most useful part of their analysis is their criticism of earlier, academic, studies which found great financial advantages accrued to the TBTF banks.

The problem with some earlier studies, the GS research points out, is that they included non-bank financial institutions (REITs for example, or asset managers) which naturally have higher funding costs than large banks, thus making the large banks’ cheap funding appear more advantageous than it really was, or is.

Other studies, they point out, included a wide range of global financial institutions such as Albanian or Uzbekistani banks – which is admirable from a diversity standpoint – but probably irrelevant for analyzing the specific US problem of TBTF banks.

Finally, the GS research highlights the key point that large companies in any industry often enjoy lower funding costs, from a combination of efficiency, perceived stability, and the relative attractiveness of larger, more tradable, securities.

All of this makes sense to me and has given me a more skeptical view of studies which purport to show the ‘unfair’ funding advantages of TBTF banks.

But they asked the wrong question

On the other hand, however, it’s a terribly incomplete view of TBTF, as the authors limit their study to the pure financial effect of an implied government guaranty.

They ask the narrow question: Is there extra money to be made by TBTF banks by virtue of their TBTF status? The answer to the narrow question is not terribly interesting: Yes there was a little extra money before, and a lot of extra money during the crisis, but none now.

I appreciate the question in pure financial terms, and I can agree, but I’m afraid it misses the bigger point.

The bigger point about TBTF is that if the largest financial firms have a government backstop – which still hasn’t been removed 5 years after the crisis – then how can these firms be considered private enterprises?

What I mean by that is that if taxpayers remain on the hook, ultimately and in nearly unlimited size, for future catastrophic losses, then how do we allow the private enjoyment of profits by employees and investors?

I really do believe in private enterprise, and nothing makes me happier than the idea of successful investors, entrepreneurs, and companies enjoying profits for delivering services in the private market.[1]

But TBTF banks aren’t real private companies. It’s not about some narrowly defined ‘funding advantage’ as measure by bond yield spread. It’s about only surviving because the government saved your bacon, and you still pay yourself as if the private profits are truly earned and deserved.

TBTF represents the worst kind of hybrid between government & taxpayer subsidy – socialized debts – and privately enjoyed profits.[2] And I’m sick of it.

** Sorry, I had previously uploaded the paper and linked to SCRIBD, but SCRIBD removed it because I did not have copyright permission.

[1] Ok, a few things make me happier. But we’re not talking about Rihanna here.

[2] I’m on a bit of an obsessive kick right now about these problems of government and commercial hybrids, especially after reviewing Jane Jacobs’ book on the topic.

Post read (7675) times.