Under the terms of a settlement agreement between home buyers as represented in a class action lawsuit and four large real estate brokerages, standard rules of engagement will soon change somewhat between real estate brokers and their clients.

The conventional wisdom described in most news stories – hoped by consumers and feared by the realtor business – is that commissions on residential real estate sales will drop from a traditional 6 percent paid entirely by the seller, to some lower negotiated rate paid separately by sellers and buyers.

Lower transaction fees, especially for something as central to household wealth as real estate, seems like a win for homeowners, possibly at the expense of the realtor business. If real estate brokerage fees have been kept artificially high by an unspoken cooperation by big brokerage firms to cluster fees in the 6 percent range – which is the assertion of the original plaintiffs in the lawsuit – then this ruling and settlement may land the average fee at a much lower range, like a 3 to 4 percent range.

Possibly no change

In conversations with real estate professionals, however, their belief overall is that this settlement will likely lead to very little observable changes, especially in Texas. On the other hand, the settlement may have unintended consequences that actually hurt consumers. Mandated changes will go in effect August 14 or later, so we’re still in speculation mode.

Far from lamenting upcoming changes to her industry from this settlement, realtor Carolyn Rhodes of Kuper Sotheby’s International Realty in San Antonio told me “this is the best thing that has happened to us in 10 years.” She explained her confidence stems from two points. First, the rules of the settlement will mandate written agreements for buyer-side representation, and it will restrict certain types of commission listings by seller’s agents which might have been used to enforce – again in an unwritten way – a 6 percent standard commission. But Rhodes says reforms in Texas in the 1990s and 2000s already mandated buyer-representation contracts, and also already made commissions explicitly negotiable. Far from putting downward pressure on commissions, her theory is that new rules will lead to better disclosure and dialogue about brokers’ fees, which helps her business rather than hurts it.

Outside of Texas I heard the same thing from Nicole Webb of Realty Executives in Knoxville, TN. She doubts the settlement will have any negative impact on her business. For starters, she says she’s rarely listing a property for a full 6 percent commission (she actually said “never”) so does not think downward pressure on commissions will be any adjustment for her. Next, she’s confident that she talks to clients upfront about how commissions work, what costs they cover in terms of marketing and advertising. And finally, like Texas-based brokers, she would always have had in place a written agreement with clear rules of engagement as a buyers’ broker. (Disclosure: Webb is my wife’s first cousin, once removed).

Another real estate broker friend I spoke with who asked to remain anonymous expected very little change in her business. As a well-established broker who relies primarily on relationships and deep knowledge of her coverage area, she felt confident that future commissions would reflect value-added work in line with past commissions. Many of those were already negotiated away from the “standard” 6 percent anyway, based on the size or complexity of the transaction.

The details of the settlement

Regarding the details of the settlements over the past few months, large brokerage firms Keller Williams, Anywhere, RE/MAX, and HomeServices of America were all sued by a group of home sellers. Anywhere and RE/MAX settled before trial, paying $83.5 mm and $55mm respectively.

A jury then ruled against the industry, and a judge ordered the National Association of REALTORs (NAR), Keller Williams, and HomeServices of America to pay damages of $1.8 billion. NAR agreed to pay $418 million, and Keller Williams settled for $70 million. In April 2024 HomeServices of America, owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, finally settled for $250 million.

A central feature of the settlement is that when agents list property on the Multiple Listing Service (MLS) database of properties for sale, they’re now much more restricted in how they communicate on this listing about commissions. They can’t require a cooperative relationship between seller and buyer when it comes to commissions. They can’t filter listings by compensation. The intent is to make it more likely that seller’s agents and buyer’s agents are totally separately compensated, and they negotiate their own compensation separately with their own clients.

Risks for homebuyers

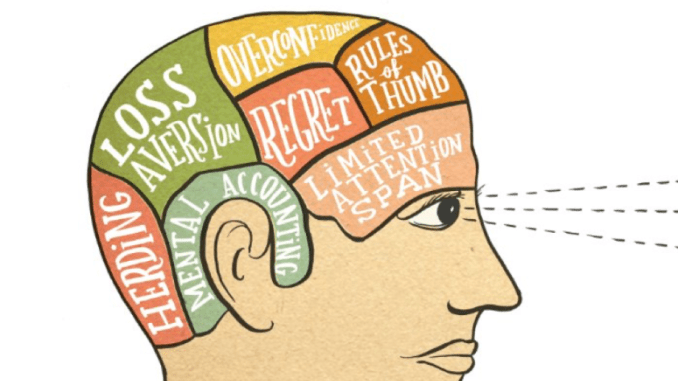

One possible unintended consequence of this settlement, commented on by a few brokers I spoke with, was the risk that some consumers may actually be harmed by the settlement.

That’s the speculative worry of J Kuper, president of Kuper Sotheby’s. In particular, homebuyers expected to pay for their own buyer’s representative face a problem. Under current rules that pre-dated this settlement, banks who offer mortgages at a real estate closing may not include buyer’s commissions in their loans. The result? Buyers may have to pay the 1 to 3 percent commission at closing, on top of the already-difficult-to-save-for down payment. If banks do not adjust their rules on mortgages in coming months, this could leave home buyers scrambling for extra cash at closing, or incentivize them to forgo representation. Neither is an outcome that will serve home buyers interests well.

Steve Yndo has been a long time broker for King William Realty and currently is a developer and commercial broker at Yndo Urban in San Antonio.

Although his bread-and-butter is not residential real estate, he also foresees complications from the settlement and new rules.

As Yndo says, “The biggest pitfall, the biggest problem might be that if the prevailing deal becomes ‘Hey sellers, you’re now expected to only pay for the seller rep’ and they’re only going to pay those guys half the current prevailing fee, then buyers are kind of on their own.

In concrete financial terms, what Yndo describes goes like this: A first-time home buyer diligently gathers her $60 thousand down payment for her $300,000 dream home. Or $30 thousand down-payment for a 10 percent, or whatever. And the new rule may require her to come up with an additional $6K to $9K at closing to compensate her buyer-side broker.

So as Yndo speculates: “What first-time buyer is able to pay that fee, unless the practice also becomes that the fee just gets rolled into the deal and as part of the mortgage? Which is more or less how it has always worked. If that doesn’t come about…[Buyers] may go unrepresented, trying to do it on their own.” Since that buyer’s fee isn’t financeable under current rules, there may be a problem in the future.

J. Kuper’s strong belief is that real estate markets depend more than anything on stability and clarity. The uncertainty around adjusting to the new settlement is what could slow down transactions, not the substance of the settlement itself, which he finds, like his colleague Rhodes, not particularly worrisome.

In May 2024 not all the details are yet known. A final agreement on new rules of engagement are still being worked out, and will not take effect for real estate transactions until August 17 2024 at the earliest or the months after, adding to uncertainty for real estate industry professionals.

A version of this ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle

Post read (92) times.