A recovering banker should engage in conversation about the ongoing income and wealth disparity between the very top and the rest of US society – among the top 10 important economic topics[1] for all Americans.

A recovering banker should engage in conversation about the ongoing income and wealth disparity between the very top and the rest of US society – among the top 10 important economic topics[1] for all Americans.

Chrystia Freeland takes on this topic directly with her useful analysis in Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else .

.

Freeland’s proximity to plutocrats as a business journalist for the Financial Times and more recently at Thompson Reuters – she works among them but is not of them – allows her to be close enough to recognize their humanity and real strengths, but also to critique them – and the global forces at work that led to their rise.

The Rise of the Plutocrats

Freeland uses anecdotes, academic research, and data to explore the causes and consequences of the rise of an ultra-rich global cohort. An early 21st Century phenomenon, they command the most impressive concentration of wealth at the top[2] of their respective societies since the late 19th Century Gilded Age in America.

Freeland does not concentrate on the so-called 1%, not even the top 0.1%. The plutocrats of her focus occupy an even higher Olympian perch of wealth than that.[3]

She describes how the plutocrats as a group are the “working rich,” often earning their wealth in their lifetime and typically continuing to work extraordinarily hard long after they’ve “made it,” far beyond any material requirements in their own lifetime.

Driven by ideals and ideas

The plutocrats in Freeland’s description – especially in the US – are people of ideas and ideals, motivated not by avarice but by the thrill of the big idea or the key innovation. Their status derives from philanthropy or from attending TED Talks, The World Economic Forum at Davos, or the Council on Foreign relations, more than it derives from the traditional accumulation and display of yachts, castles, and polo teams.[4]

Freeland points to two powerful forces which have facilitated the rise of the new plutocrat class. First, in what she labels the “Marshall Effect,”[5] a widespread increase in societal wealth often leads to an even great concentration of wealth among top performers. Increased wealth outside of the traditionally richer Western World, for example, has benefitted not only newly developing countries but the capitalists of the older developed countries as well.

Second, in what Freeland labels the “Rosen Effect,”[6] certain newer technologies have allowed for scale-ability in markets and therefore even greater outsized compensation for superstars. The very top performers in a given area can access a ‘personal market scale’ previously unimaginable in earlier eras.

These twin effects strike me as accurate explanations for the rise of global plutocrats, and Freeland provides myriad anecdotes from her research to flesh out the role of globalization and technology in the creation of a plutocrat class.

Freeland usefully describes the new billionaires of fast-changing Russia, China, India, and Mexico as well. Their rise, in Freeland’s telling, owes relatively more to ‘rent-seeking’ behavior than to the idea-driven technological breakthroughs of Silicon Valley. ‘Rent-seeking’ is economist-speak for capturing underserved economic advantages through non-productive and illegitimate activities such as bribing government officials or the indirect capture of regulatory bodies to achieve profitable, private monopolies.

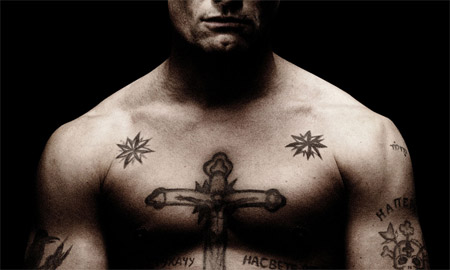

The Russian Oligarchs

Freeland’s prose strengthens when she describes the rise of the Russian oligarchs over the last 20 years, previously profiled in her book Sale of the Century: The Inside Story of the Second Russian Revolution. The similarities and differences between Russia’s plutocrats and plutocrats in, say, the United States bear exploring.

The Russian oligarchs represent a clear example of extraordinary wealth acquired by a tiny number of men through illegitimate means during the chaotic privatization of the 1990s. Whatever the oligarchs come to represent for Russians in the future, for now, at least, they indelibly stamp Russian-style capitalism as fundamentally unfair. Non-plutocratic Russians can’t help but feel the game to acquire wealth has been fundamentally rigged against the meritocratic, but unconnected, capitalist.

Later, Freeland describes quickly but convincingly how China’s financial elites owe much to their close ties to the ruling political elite,[7] the way India’s plutocrats engage in outright bribery with regularity, and why Mexico’s Carlos Slim – the world’s richest man – is the capitalist Mozart of rent-seeking behavior.

The US traditionally celebrates its plutocrats

Traditional US society has long legitimized and celebrated its plutocrats, from JP Morgan a century ago to Bill Gates over the past twenty years. Even if we could not all create the next ‘killer app,’ mainstream Americans embraced the myth that almost anyone could, with enough pluck and luck, be the next Mark Zuckerberg.

More than any other culture in the modern age, US citizens traditionally believe that the game is not fundamentally rigged against the merely meritocratic, but unconnected capitalist. Market-oriented capitalism, for all its failings, seems legitimate, to most people.

In the post-Great Recession environment of the United States, characterized by the Occupy Wall Street movement and a newfound distrust of the means of wealth acquisition among the 1% and above, however, I think Americans need to discuss the extent to which society in the United States continues to believe in the system’s legitimacy.

By anthropologically cataloguing the habits and habitats of Russia’s oligarchs, China’s new billionaires, and the US’s tycoons, Freeland suggests the question of legitimacy.

Not a conspiracy in the US, but cognitive capture

In the final two chapters Freeland offers a nuanced description of the way in which the US system, at least with respect to financial regulation, is rigged in favor of the very top.

While financial elites do not typically engage in outright bribery or transfer of wealth from public to private hands in the US, they don’t need to go that far to tilt the rules in their favor.

“Cognitive” or “systemic” capture – the way in which elites in government or regulatory roles adopted the Wall Street perspective as their own perspective – does the work in place of an outright conspiracy.

As Freeland writes:

“[T]he real story isn’t one of individual corruption. It is…about systemic capture. The vampire squid theory of the super-elite is entertaining and emotionally satisfying. It can be fun to imagine the super-elites who went to Wall Street and their Harvard classmates who became economics professors and those who became US senators participating in a grand conspiracy (hatched ideally, at the Porcellian Club) to rip off the middle class. But the impact of these networks is much less cynical, and much more subtle, though not necessarily of less consequence.”

During the 2008 Credit Crisis, the fact that then-Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson grew up professionally at Goldman Sachs, and personally knew very well all the heads of Wall Street firms as colleagues and competitors, drove the Wall Street-friendly bailouts.

You don’t need to be a conspiracy theorist, or even a believer in any outright corruption, to acknowledge that Paulson’s world view – that what was bad for Wall Street would be bad for Main Street – drove his very-few-strings-attached-just-save-them-at-all-costs generosity to the Too-Big-To-Fail Banks.

I think Freeland’s nuanced explanation of “cognitive capture” explanation goes a long way to explain the 2008 Credit Crisis and our inability to rein in the TBTF banks better than any conspiracy theory.

Some quibbles about the book

Chrystia Freeland’s Plutocrats toggles between several modes of business-writing, not all of which successfully interact.

Less usefully, but perhaps inevitably, Plutocrats offers up tidbits of voyeuristic gossip, as Freeland name-drops her elbow-rubbing and panel-facilitation with the ultra-rich in places such as Davos, Sun Valley, and Aspen. I cringed a little at reading some of this, but then again, what was I expecting? I suppose we all need to compare the contradictory clichés of “Stars! They’re just like us,” versus “The rich really are different from you and me.”

Worse, Plutocrats sometimes reads as a traditional, business-school-style “How to,” book, offering anecdotes and bromides from current plutocrats for aspiring plutocrats to emulate. We learn in Chapter 4, “Responding to Revolution” that emerging markets offer opportunities for faster growth than the traditional Western ‘developed’ countries. Further, successful wealthy entrepreneurs excel at exploiting opportunities, and the ability to guide their startups through a crucial business-direction “pivot.”

Groan.

A missing explanation for the rise of Plutocrats in the United States

Freeland leaves out an exploration of how changes in the tax code in the United States in the last 30 years – especially with respect to top marginal income tax rates, dividend taxes, capital gains taxes, carried interest taxes, and inheritance taxes – institutionally spur income and wealth inequality, especially at the 1%, level, 0.1% level, and above.[8]

Wealth at the highest level inevitably is wealth derived from equity ownership; that is to say, derived from business earnings rather than salaries. When Congress dramatically lowers top marginal income, dividend, capital gains and inheritance taxes – as has happened in the US in comparison to 1980 – it increases personal incentives for highly unequal compensation.[9]

Reasonable people, from different places on the political and economic theory spectrum, could debate the relative merits of this trend in tax policy, but I think its absence from Freeland’s discussion of the rise of massive wealth and income disparities, at least in the US, weakens her explanation.

Please see related post: All Bankers Anonymous Book Reviews in one place.

[1] I’m still working out what the other Bankers Anonymous topics should be. So far, in addition to massive income and wealth concentration at the top, I think they are: What to do about Too-Big-To-Fail banks in the US; What should every adult citizen understand about personal finance; What are the consequences of the finance industry attracting such a high proportion of elite talent (rather than technology, education, medicine, engineering, social services, etc); How not to invest; Is poverty in the US an inevitable consequence of relatively free markets, or a failure of societal empathy; and What the hell really happened in 2008? That’s what I have so far. I’m open to further suggestions from readers to round out my top 10.

[2] Freeland describes different layers of the plutocratic stratosphere, at times changing levels without prior notice. Mostly she means to describe the extraordinarily wealthy, although she never defines her ‘cut-off’ level to qualify as a plutocrat. She cites the existence in 2011 of 84,700 Ultra High New Worth Individuals (UHNWI, as coined by Credit Suisse Bank), in the world – defined as owning $50 million in assets. One can infer from her descriptions that she means to start somewhere near the low-end of “Mitt Romney wealthy” of say, an estimated $200 million, and go up from there. At times in Plutocrats, however, she downshifts to describe the habits and rise of the merely wealthy, entrepreneurs or Wall Street employees in the $50-100 million net worth range.

[3] Freeland makes the important point to distinguish gradations within the so-called 1%. According to Freeland, the top 1% of earners in 2007 reported an average income of $486,395. These, most decidedly, are not plutocrats. Further up the mountain, there were 134,888 taxpayers in the top 0.1% in the United States in 2007. Still too many. The US has 35,400 UHNWI, boasting $50 million or more in assets. Getting warmer. A smaller number, 15,000 Americans, reported average annual incomes of $23.8 million, constituting the top 0.01%. Only 412 US citizens were billionaires in 2007. The number of plutocrats seems to be somewhere between 500 and 15,000 in the US.

[4] The three plutocrats I’ve known in my own life, each from the United States, all fit Freeland’s type. They worked extraordinarily hard at creating wealth in their own lifetime. Equally striking, they dedicate extraordinary passion and energy toward their educational and medical philanthropies respectively. They are curious, generous, and personally modest in affect.

[5] 19th Century economist Alfred Marshall noted that while the 1st Industrial Revolution led to a rise of incomes broadly, certain individuals reaped outsized returns from the rising tide.

[6] 20th Century economist Sherwin Rosen pointed to technological gains to explain the concentrated success of superstars in a modern economy.

[7] One side note on China that I found (gruesomely) fascinating: Freeland cites an article that Chinese authorities executed 14 billionaires between 2003 and 2011, presumably on corruption charges. I cannot even fathom the kind of changes that would have to come about in US society to see 14 billionaires executed on corruption charges. In a related story, apparently Chinese billionaires keep a much lower public profile than their counterparts in Russia, India, Mexico, or the United States.

Post read (11257) times.