According to Social Security, about 2 million people are subject to something called the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) which reduces Social Security benefits in retirement. This affected 200,309 Texans receiving Social Security payments at the end of December 2021, more people affected than in any state except California.

The WEP usually hits when income over a lifetime is split partly between a public sector job with a pension and some years of contributing to Social Security.

So if you are a public sector employee with a pension – like a firefighter, police, or public school employee – you’ll want to pay attention to how the WEP may affect your Social Security payments in retirement.

In Texas, an estimated 95 percent of public school district employees do not pay into Social Security, according to the Teachers Retirement System, putting them in a relatively high likelihood of being affected by the WEP. Texas police and firefighters, as well as city or county officials may also be negatively affected if they do not participate in Social Security for most of their career.

The problem is the WEP is notoriously complicated to understand. I’ll explain who and why you might be affected, who shouldn’t worry, and what if anything you can do about it.

To further clarify, the WEP is notoriously unrelated to any song by Megan Thee Stallion. If you do not already know what I’m talking about then I implore you do not – under any circumstances – check YouTube right now to inform yourself.

The reason for the WEP

In order to understand the idea behind the WEP, you have to know a key thing about Social Security retirement benefits design. The main thing to know is that – as a welfare program – Social Security benefits nearly match earnings for the lowest paid people. Once you graduate to medium or higher pay, by contrast, your earnings only get somewhat matched by Social Security. If you make medium or high pay, you will receive a higher benefit from Social Security than a low-paid person, but only slightly higher, and not proportionate to your higher pay.

A couple of central scenarios make you subject to the WEP. The first would be if you are a salaried public employee contributing to a public pension rather than Social Security, but then you also earn some other modest amounts of money on a side hustle for which you do pay into Social Security. This could happen if you’re a teacher who takes a summer job that pays into Social Security. Or you are an owner or part owner of a business, and that business pays into Social Security. Or you work part of your career in a job that pays into Social Security, but then switch into a public pension job that does not pay into Social Security.

In each of these scenarios, the WEP is there because according to Social Security it would be unfair to accumulate a bunch of low-pay Social Security credits which then get highly matched with benefits. If you made $15,000 a year in a summer job as a teacher, but mostly make money throughout the year as a teacher with a pension, Social Security wants to more highly reward the person who actually only makes $15,000 a year total, rather than $15,000 as a side hustle. Essentially, that second person needs the welfare benefits of Social Security more than the public pensioneer teacher, according to the WEP theory.

So the WEP reduces the amount of Social Security the public pensioner receives in retirement, as a “fairness” provision relative to low-paid people who really depend on Social Security, rather than a pension.

Scale of Social Security reduction

Another key thing to know is that whatever amount you are owed by your pension, that part is safe. The WEP only reduces your Social Security benefits, not the pension benefits. But by how much?

Under the worst case scenario in 2022 the WEP can only reduce your Social Security payment by a maximum of $512 per month, according to Oscar Garcia, a former Social Security Administration employee and consultant now with Your Social Security Strategies.

That $512 maximum ceiling will shift to something higher in the future for future retirees.

Garcia used to write a regular newspaper column about Social Security and is deeply fluent in WEP.

Another limit to the WEP pain is a provision that protects people who only qualify for a small pension through their public sector career. Social Security will only reduce your benefit payment by one half the size of your pension. So if you only get $300 per month from your pension in retirement, your Social Security benefits will only be docked by $150 per month, because that’s half your pension.

What Can Be Done? Can the WEP Be Avoided?

For people who have only accumulated some Social Security benefits over a lifetime, and will receive a significant public pension, not a lot can be done.

Any public pension-eligible employee who manages to accumulate 30 full years paying into Social Security won’t be hit by the WEP. Anyone who accumulates between 21 and 30 years earning a substantial income subject to Social Security also is partially protected from the WEP, on a sliding scale as they approach 30 years. Of course, it’s hard to simultaneously work 20 to 30 years of paying into Social Security while also qualifying for a public pension, but it’s theoretically possible.

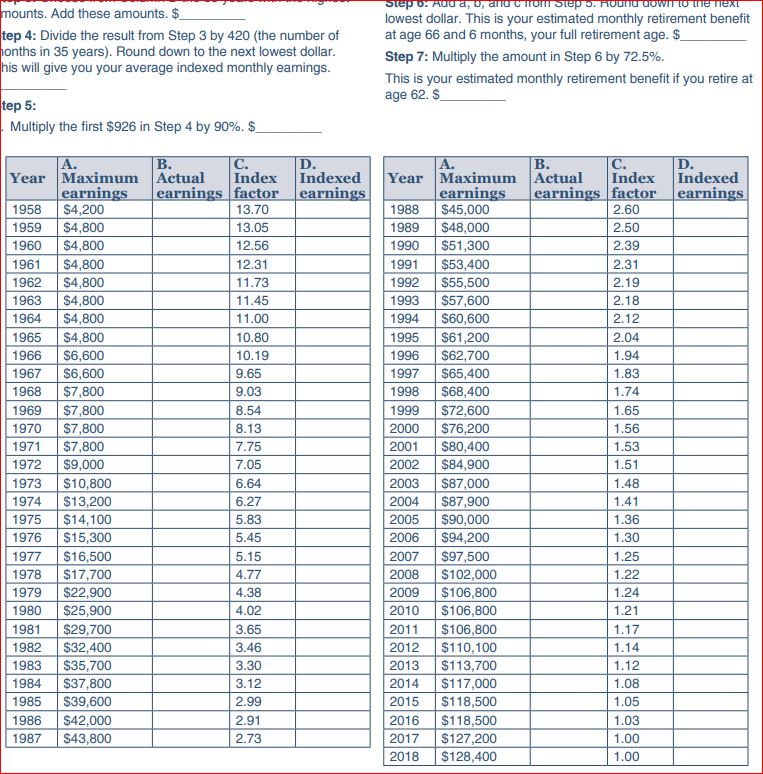

Other than that, the best defense is forewarning through knowledge, and people worried about the WEP can go to an online Social Security calculator.

To use this effectively, you would need to know all your past years of earnings, as that’s how Social Security calculates the WEP. If you haven’t previously signed up for a personalized benefits estimator through a website called MySocialSecurity, that’s also very worth doing and the best way to get your past earnings.

The WEP is generally quite unpopular with public pensioners who figure out the money they’ll not receive from Social Security, so attempts are made regularly to repeal it, so far unsuccessfully.

In July 2019, Texas Congressman Kevin Brady (now House Ways and Means Republican Leader, then Chairman) introduced the “Equal Treatment of Public Servants” bill to replace the WEP with a new proportional formula that would have raised Social Security payments for most but reduced them for others, based on average time in one’s career spent paying into Social Security. Texas Senator Ted Cruz introduced the companion bill to Brady’s bill in March 2020.

In 2021 Congressman Brady again introduced a WEP-elimination bill, with support from 15 other congress members from TX.

The Texas Lege also sent a resolution to Congress in April 2021 urging Congress to fix it.

Further attempts have been made in recent years to repeal or reform the WEP from both Republicans and Democrats, but so far the WEP lives on.

A frequently lumped-together and somewhat relatedly-hated problem, known as the Government Pension Offset (GPO to the cool kids) also can reduce Social Security spousal benefits. I’ll address that confusing story in a subsequent column.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Expresss-News and Houston Chronicle in September 2022.

Please see related posts

Social Security and the GPO

Post read (174) times.