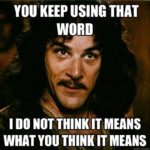

When I think about environmental action, my mind goes to the words we commonly use – particularly “sustainable” and “green.” And like the Princess Bride’s Inigo Montoya, I do not think these words mean what traditional environmentalists think they mean.

When I think about environmental action, my mind goes to the words we commonly use – particularly “sustainable” and “green.” And like the Princess Bride’s Inigo Montoya, I do not think these words mean what traditional environmentalists think they mean.

Because of my particular definitions, I am oddly excited about my city’s organic compost plan. I’ll explain why in a moment, but first, those words.

To me, an environmental plan is “green” when we make money or save money – cool, paper, greenbacks. A “sustainable” environmental plan is one that continues because everyone sees it as in his or her own personal financial self-interest. A “sustainable” environmental action, therefore, is one not easy stopped by a political change or a slight shift in market prices. If people want to do the right thing environmentally and it’s also in their interest financially, then that action will sustainably continue.

Ok, so why do I get all tingly about my city’s green organic composting barrel that showed up at the end of my driveway a few months ago?

After a little bit of research I found out that a business managing organic waste can make money – in a green, sustainable way. As it turns out, my city, and indirectly taxpayers, can save money from organic composting. The final piece – the specific financial benefit for households – is only weakly established, in my opinion. San Antonio is working on this as well, but that’s probably the part that needs the most strengthening in the years to come.

Figuring out how a private business makes money is why I visited the headquarters of New Earth, the company that has the contract with the City of San Antonio to collect organic household waste.

In theory, I’m enamored of their business model. They get paid to take in raw waste, and they get paid to sell compost. Getting paid both coming and going!

In theory, I’m enamored of their business model. They get paid to take in raw waste, and they get paid to sell compost. Getting paid both coming and going!

Organic waste dumpers – like landscapers, tree-clearing developers, and now the City of San Antonio – pay New Earth for the privilege of dropping off organic trash, the first source of the company’s revenue. New Earth then applies its processes – the art and science of industrial-scale composting – to that waste over 1 to 3 months. At the end, they produce ground cover, mulch, and compost bags for sale to landscapers, developers, and gardeners.

Of course, I’ve simplified the attractiveness of New Earth’s business model.

Like any real business, profit is not as easy as it at first seems. New Earth takes considerable financial risks.

Here’s just a sample of why it’s risky: Handling trees and brush cleared from a new construction site is relatively easy – you run the trees through a chipper and you have a relatively uniform product at the end. However, properly filtering household organic waste – produced from hundreds of thousands of sometimes careless trash-tossers like you and me – is a far more risky and manual-labor intensive process. Clayton Leonard – until recently the President of New Earth – explained to me that New Earth had to double their workforce to handle the city contract. They also had to invest in a multi-million dollar piece of equipment to sort through the waste. Leonard climbed up with me onto one of their giant sorting machines.

We watched the household waste pass through a conveyer belt while guys with rakes – some of their new hires – separated the non organic waste from the pile. Pro-tip: Neither your old iPhone case nor your plastic bags should go into organic waste. Not all households, I saw from the conveyer belt process, have gotten that memo.

We watched the household waste pass through a conveyer belt while guys with rakes – some of their new hires – separated the non organic waste from the pile. Pro-tip: Neither your old iPhone case nor your plastic bags should go into organic waste. Not all households, I saw from the conveyer belt process, have gotten that memo.

I mention all this to say that it takes significant capital and labor costs to try to make money on a citywide organic waste contract. The key point for me, however, is that New Earth is being run in my version of a green, sustainable way – to make a profit.

At the same time, the City of San Antonio has their own green, sustainable, reasons – saving money. Here’s how.

When the city hauls and dumps regular trash, it pays an average of $24 per ton to local landfills for that privilege.

When the city hauls and dumps organic waste over to New Earth it pays $16.50 per ton. The city is incentivized therefore to redirect as much volume of trash as it can to organic waste. As New Earth’s Leonard told me, “In order for us to survive, we have to be cheaper than a landfill.”

As the city fully rolls out the green barrel program – scheduled for completion in April 2017 – it hopes to get a lot of residents dumping their compostable waste into those barrels. The goal for the household organic waste program is 60,000 tons per year, according to Nick Galus, Assistant Director for the Solid Waste Management Department. At current prices, that would save an estimated $450,000 per year.

As the city fully rolls out the green barrel program – scheduled for completion in April 2017 – it hopes to get a lot of residents dumping their compostable waste into those barrels. The goal for the household organic waste program is 60,000 tons per year, according to Nick Galus, Assistant Director for the Solid Waste Management Department. At current prices, that would save an estimated $450,000 per year.

As a public entity, Galus notes, their goals are a combination of financial gains and sustainability, traditionally understood.

“Our goal is to capture the greatest amount of the waste. The cost isn’t the driving force. We’re trying to get to our goal in the most cost-conscious way,” he said.

Interestingly, San Antonio is the first major Texas city to roll out an organic recycling program city-wide. The fact that other Texas cities haven’t done the same – despite some financial incentive to do so – indicates that there are risks for a city as well. Any city, including San Antonio, has costs for rollout and household education. Other Texas cities have pursued strategies focused on yard waste, according to Galus, making it costly to switch over to a plan that also accommodates food waste.

The San Antonio goal is to have 60 percent of all waste hauled by the city be recycled, composted, or repurposed in some way by 2025. They’re at 33 percent as of 2016.

If San Antonio can show cost savings, the case becomes more compelling for other cities. If they can even figure out the household financial incentives, the whole process becomes my kind of green and sustainable.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Post read (220) times.