Like baseball, young love, and hay-fever, we’ve entered the high season for taxes.

New this year, however, we begin to react to changes in the tax reform law of December 2017. The point of that law was to make the world safe for businesses and their owners, who received healthy tax cuts. If you were not already a business owner, I’m sorry to say the tax reform was really not about you. But, I quipped at the time the bill was passed, you should hurry up and form your LLC or C-Corporation in order to participate in the tax reform largesse. If you are neither a business owner, nor planning to take my advice to form your own business entity, may I make another suggestion? Just go outside and forget reading today’s post about business taxes. Enjoy the day. It’s beautiful out there. I love Spring! Buh-bye.

Ok, great, now that it’s just us business owners, let’s get into the nitty-gritty details.

I’m sure you already know that traditional corporate owners – people with C-Corps – won big in December by getting tax rates on profits dropped from 35 percent to 21 percent. High Five![1] That was awesome.[2]

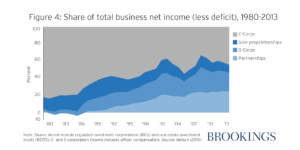

But the main thing to dig into here is not about traditional C-Corps, but rather the more flexible businesses like limited liability companies (LLC), limited liability partnerships (LLP) or sole proprietorships.

A huge range of businesses, including especially small businesses, choose this type of business structure for the greater flexibility, low costs, and ease of administration.

A huge range of businesses, including especially small businesses, choose this type of business structure for the greater flexibility, low costs, and ease of administration.

As you no doubt already know, profit from these so-called “pass-through entities” – LLCs, LPs or sole-proprietorships – has for taxation purposes generally been passed through to the owners, just as if they were salaried employees. This means that a high-earning LLC owner potentially pays high tax rates, because personal income tax rates are much higher than corporate rates. Starting in 2018, that highest personal rate is 37 percent – which is now so, so much higher than the corporate tax rate of 21 percent.

Given the massive tax cut for C-Corp owners, and the massive popularity of pass-through entities like LLC, it seems only natural that the tax reform would reward pass-through entity owners somehow. And it did! Pass-through entity owners (remember: LLC owners, LPs owners, sole-proprietors) get to take a 20 percent itemized deduction from income. Which is also awesome! Again, high five everybody. Given that deduction, the main idea is that remaining a salaried employee is really for chumps, compared to being a C-Corp or LLC owner.

So here was my logical thought, upon passage of that law. I need to start charging for finance blog posts,[3] not as an individual, but rather as, for example, “Mike’s Bankers Anonymous LLC.”[4] That should get me the 20 percent deduction off total income, saving a lot in taxes. And like, basically, everybody needs to do the same thing, selling their labor through a pass-through entity, rather than work directly as an employee. What if Mr. Bustlebee sells his librarian services to the local public library through his new business named “Shhh Quiet People are Tring to Read Here LLC?” Bada-boom! 20 percent deduction in taxable income for a librarian.

I recently ran this amazing scheme past my accountant. On your behalf, Mr. Bustlebee.

But my accountant Noah Rifkin, a principle at MBAF in New York City, quickly burst my bubble.[5] The IRS does not want my trick to work for people, or at least for people who make lots of money. It turns out, Rifkin says, my idea totally does not fly as a tax dodge.

One lesson, as always, is don’t take tax advice from a newspaper columnist or finance blogger.

One lesson, as always, is don’t take tax advice from a newspaper columnist or finance blogger.

The 20 percent deduction on income from pass-through entities, my accountant explained, can’t be claimed by huge swathes of LLCs engaged in everything from law, health, accounting, performing arts, consulting, athletics, brokerages, actuarial science, and financial services.

Rifkin describes the 20 percent deduction as claimable mostly for businesses that produce “widgets,” that catch-all accounting word used to denote anything manufactured and sold as a product. Not, in other words, a personal service, like I was hoping. The 20 percent deduction isn’t supposed to be claimed for any LLC-type business that depends on, to quote the explanatory paper my accountant sent me, “the skill and reputation of one or more employees or owners.”

Well, I intended to claim that writing a blog does not involve any skill and neither do I have a reputation! Surely you agree? If all readers would continue to vouch for that statement in writing, to both the IRS and my editors, I think this plan could still work.

Slightly more seriously, the law has created some interesting grey areas. The Wall Street Journal gives the example of two restaurants organized as LLCs. One highly profitable restaurant succeeds based on the reputation of a celebrity chef, and therefore can’t take the 20 percent deduction. The other profitable restaurant, succeeding without the celebrity chef’s reputation, might be able to take the deduction. That’s kind of an odd result.

Despite what my accountant says, and all jokes aside, my plan still might work for many people. If you make less than $315,000 as a married couple, or $157,500 as a single filer, you can still claim that 20 percent LLC income deduction, despite being in one of these disqualifying businesses like law or health or accounting or blog-writing that supposedly involve skill and a reputation.

Since 97 percent of people earn less than $157,500, I still say a great number of currently salaried workers could form an LLC, sell their labor though the entity, and potentially save on their taxes. I hope Mr. Bustlebee the librarian is currently scheming with Mrs. Busybody the teacher to form their limited partnership together.[6]

My accountant doesn’t agree with me at all. But, you know, check with yours.

[1] “High Five” is said in the Borat voice, obviously.

[2] By the way, does anybody else here hear and think of the phrase “see corpse” when talking about taxable business entities? Not so much? Nah, me neither. That’s gross.

[3] I know this is illogical, since I don’t actually charge for blog posts, but I’m just trying to suggest whatever activity you do professionally, you should charge though the business entity, not as labor.

[4] Actually I do have a single-member LLC, and when I make consulting income I charge through the LLC, so I’m already taking my own advice. But you should do the same.

[5] Rifkin is a real person, unlike Mr. Bustlebee, who is a figment of my Dickensian-naming imagination.

[6] And you have to admit, that’s hot.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Post read (359) times.