I have a theory: The definition of ‘being wealthy’ links in some way to thinking about, and being cognizant of, death.

Death

Death of course gives me the willies. I actually get vertigo if I think about it in bed just before falling asleep. I suddenly feel wide awake and unsettled. The whole thing feels super unfair to me. Like, I get to stress and struggle and work and procreate and nurture and then struggle some more – and then after fifty or maybe even ninety years my time here runs out? No exceptions? Even if I promise to be really, really good? Fuck that.

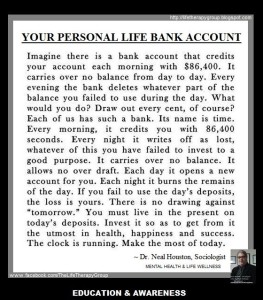

Occasionally, I rise about my selfish thoughts into moments of higher consciousness. Sometimes this happens if I’ve been to really good funeral. When surviving friends and family tell good stories about a well-lived life. That’s when thinking about death helps sharpen my ideas about how I should live. My choices about how to spend precious time that I can’t get back. The bank of time that empties out every day. The irrelevance of so much and the relevance of other stuff. The fierce urgency of now.

Sometimes in those moments I get insight into what it means to be wealthy. The earning of money and the having of money, compared to one’s limited time remaining. How much money do you need to purchase back control over your own time?

Or if death was imminent, how much money would I be willing to pay for another year of sunrises, Dairy Queen dipped cones, and snuggles with my girls? Of course I’d turn over all the money I had. And if I am lucky enough to have years and years of that ahead of me? Well then, I’m as wealthy as a king.

Money and Medicine

Gawande does not concern himself – except tangentially – with the financial consequences of end-of-life medical interventions, although we know these are an extraordinary and growing public expenditure problem.[1] He concerns himself instead with the human consequences of end-of-life medical interventions.

We know medically how to keep the human body alive. We can treat the symptoms of old age. We can often push back against former death sentences like cancer. We patch up and retool failing body systems far longer than we ever could just a generation before.

What we don’t know – and what Gawande wants us to think about – is when to say “when.” In our rush to fix failing organ systems, do we fail to ask the key questions of a dying person like “What are your goals?” and “what are your fears?”

Gawande finds that, when given a chance, some choose to spend their remaining time alive differently. We all die eventually, but we don’t live the same way, during our dying time. A few weeks in hospice care without extraordinary medical interventions (reduced pain, reduced disorientation, increased dignity) may beat months of throwing all of our latest technology at our dying body.

From what I gather, most of us (in conjunction with our families and doctors) have a hard time parsing these choices. We are a long way from asking the right questions. We forget the odds of achieving a high-quality life through additional medical procedures.

Gawande is such a good writer that he makes a hard topic into a compelling read, but this isn’t easy reading by any means. I have never read such a series of explicit descriptions of what happens to us – what will happen to all of us – if we are fortunate enough to die slowly. Gawande tells the stories of his patients, and then most poignantly, his own dying father. We learn just how excruciatingly difficult it is to NOT always choose the next medical intervention.

Back to Being Wealthy

Being wealthy has something to do with owning one’s time. I think it has something to do with understanding the relative value of a high quality life. It certainly has something to do with being able to afford high-quality medical treatment, although that probably has only mattered in the last one hundred years or so. At the end of life, the high-cost medical treatments may matter less and less, as we seek a return to the highest-quality life possible, with our remaining time.

[1] The old 80/20 problem again. Something like 75% of medical expenditures are made in the last year of someone’s life. Multiply that by an entire society, with the burden shared between private and public expenditure, and we’ve got soaring healthcare costs on trend to swallow up all of our money.

Please see related post:

Post read (167) times.