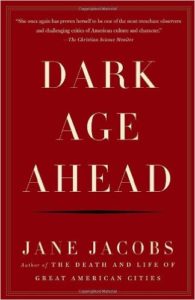

I judged this book by the arresting title Dark Age Ahead, and decided that – in my current frame of mind – I had to read it.1

I judged this book by the arresting title Dark Age Ahead, and decided that – in my current frame of mind – I had to read it.1

Jane Jacobs wrote this is 2004, and the book has a bit of the feel of a time capsule – as her current events examples stem from 2001 to 2002. Jacobs’ strength as a thinker and writer is that she can extrapolate from events in her own life, close observations, and from the newspaper, and illuminate patterns and principles of any age. She’s not academic, and she depends on telling anecdotes. Some may see that as a weakness, although I feel it’s a strength of her work. Her ‘big ideas’ tend to be right, and written in a way that an educated, but non-expert, reader can understand.

The central thesis of this book – and I tend to agree – is that invisible but essential strands of our strong society2are fraying at the edges. Her list of essential strands are not necessarily somebody else’s, but hers seem worthy of consideration, and worry. At the beginning of 2017, when the fraying seems particularly acute, its interesting to note, again, that Jacobs published her book in 2004.

So what is unraveling?

Households

Critiques of the breakdown of the nuclear family are commonly heard from the Right, but Jacobs does not mean exactly the same thing here. A main concern, she develops in the chapter, is the extreme rise in the housing prices, beyond the rise of household incomes. Now that’s interesting, since her book predates the housing crash by four years, although it was obvious to many in the early 2000s that we were on an unsustainable path brought on by low interest rates and easy credit. Her other concern – which will not surprise Jane Jacobs fans – is with the pernicious affects the automobile has had on the development of suburbs and the undermining of public transportation infrastructure.

The replacement of a true education in favor of a more “practical” set of market signals through degrees offered by institutes, community colleges and universities. The focus of educational institutions has become to offer a set of letters that indicate preparation for a specific job, rather than passion about learning or knowledge. We can only imagine how justified Jacobs would feel about the $25 million settlement made by the President-elect with respect to his fraudulent “University.”

Science Abandoned

Jacobs has a specific complaint here about the “engineers” who deal with traffic congestion – a particular obsession of hers – but we see plenty of evidence lately of the denigration of science and the scientific method. I can’t tell if the problem has gotten better or worse (probably it’s mixed) but we suffer when society fundamentally doubts scientific conclusions or discounts the need for a scientific approach.

Dumbed Down Taxes

Jacobs addresses here the problem of tax collection at the Federal level, for example, when certain problems must be solved at the local level. Or vice versa. The result is decision-making with the wrong branch or level of government. In my home state we are plagued by the problem of school funding, which is taxed at the local level, legislated at the state level, but clearly failing standards at the federal level.

Self-Policing Subverted

Specific industries sometimes do best when they self-regulate, recognizing their collective interest to seek best practices and internally police or punish wrong-doers. While acknowledging that truth, Jacobs points out examples – from architecture to police departments to accounting firms – where deeply problematic practices arise from bad self-policing.

Are these the root causes of the rest?

In her introduction, Jacobs asserts but does not prove that these five negative trends listed above over time increase the chance of a major societal breakdown. And she means “Dark Age” literally. Like, post-Roman Empire type reversion-to-chaos.

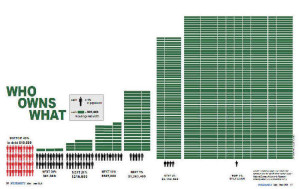

She also asserts, but does not prove, that these five are not just as consequential as a more typical list of “society-destroying trends” such as racism, environmental destruction, crime, voter apathy/distrust, and the widening gulf between rich and poor, but that they are causal. Meaning, the racism, environmental destruction, stuff etc are actually symptoms of the societal unravelling, rather than the root causes.

I don’t know if she’s right. But there’s good stuff there to chew on.

Book Review of The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs

Book Review of Cities and The Wealth of Nations by Jane Jacobs

Conflict of Interest And Moral Codes

Post read (317) times.

- My current frame of mind also has me reading Plutarch’s Fall of the Roman Republic and seeking out any signs that the center will hold, and that things will not fall apart. ↩

- Jacobs is a Canadian who lived a significant portion of her adult life in the United States, so her “strong society” comments could be considered aimed at both countries. ↩

e United States. The book also might seem to serve as an updated guide for the rest of us to make sense of the mess of race relations in the United States.

e United States. The book also might seem to serve as an updated guide for the rest of us to make sense of the mess of race relations in the United States.