Taxes form the backbone of the relationship between government and the governed, revealing most starkly what we value as a society. Spoiler alert: We value business owners and investors.

Taxes form the backbone of the relationship between government and the governed, revealing most starkly what we value as a society. Spoiler alert: We value business owners and investors.

The most dramatic proposal to emerge from “The Unified Framework For Fixing Our Broken Tax Code” announced last Wednesday from GOP leadership in Congress and President Trump is the drop in the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 20 percent. Other provisions to encourage more investment and business growth include:

- A one-time low-tax incentive for on-shoring money held by corporations overseas,

- The option for faster expensing of capital investments over the next five years, to incentivize further investment and lower corporate taxes, and

- Because 95 percent of businesses are organized as LLCs and LPs subject to “individual pass-through taxation,” paying individual (aka personal) tax rates, the proposed framework would lower top tax rates for such businesses to 25 percent, well below the proposed 35 percent top personal tax rate.

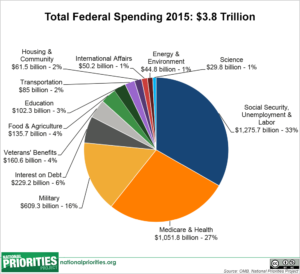

The net effect of this sweeping tax reform would dramatically lower the burden of taxes on businesses. Initial estimates of lower tax revenues as a result of the proposal cite $5 trillion less in revenue, and possibly $1.5 trillion in increased federal debt, over the next 10 years.

Do not get overly distracted by proposals regarding household or individual taxation, because the framework’s central bet is the following: If businesses are the job creators and businesses make most investments in this country, then businesses will be the engine of economic growth and national economic strength. Treat businesses well, and plentiful jobs, higher salaries, increased investment, and national prosperity will follow. That’s the guiding theory of this tax reform. If that theory turns out to be true, this reform will be hailed by future generations as a smashing success.

On the individual and household side, the proposal would reduce the need for most itemization on a tax return by doubling standard household deductions, and it proposes three individual and household tax brackets, with an option for a fourth bracket, targeted at higher earners.

Also on the individual side, the proposal would eliminate the Alternative Minimum Tax, and the estate tax, which only affects 0.2 percent of deceased’s estates. These two proposals would only benefit high earners (subject to the AMT) and the very wealthy (subject to the estate tax), respectively.

So what to think about this proposal?

First, let’s talk about simplification, a stated goal of reformers. Simplicity in a new tax code doesn’t derive from a smaller number of tax brackets, but rather from eliminating itemized deductions, loopholes, and abolishing the AMT.

Perhaps cleverly, but ominously, the framework does not specify whether and how certain deductions popular with businesses and households will survive or not. We know many targeted tax breaks (aka loopholes) must be eliminated, however, to make up revenue lost by lower corporate and household tax rates overall.

That is left, as of now, to the future sausage-making congressional committee process. The basic problem is that everybody likes to keep their own loopholes (which are job-creating and fair, naturally) while eliminating everybody else’s loopholes (which are unfair and benefit special-interests, naturally). There’s a fight to be had there.

The more sweeping the loophole-elimination, the closer we get to the Shangri-La of tax reform: tax filing on one single page, prepared in less than an hour, without hiring a tax specialist. But it’s politically challenging to eliminate loopholes to which specific powerful constituencies have become attached. Getting to simplicity, therefore, won’t be simple.

Next, let’s talk politics.

The political stakes of tax reform could not be higher for the Trump Presidency. This is his legacy moment, as well as the legacy moment for House and Senate GOP leadership.

For many, President Ronald Reagan’s signature triumph was the Tax Reform Act of 1986, forged in compromise with a Democratic House led by House Speaker Tip O’Neill. Top tax rates came down, the code was simplified, the bull market in stocks roared. We remember Reagan’s presidency as a time of increasing national prosperity. Could Trump make this his legacy too?

The political body-language between the President and the Republican leadership of Mitch McConnell in the Senate and Paul Ryan in the House has always been one of mutual wariness and uncomfortable tolerance, at best. The calculation for the fiscally-oriented wing of the Republican party, led by Ryan, is that all of it will have been worth it if they can accomplish comprehensive tax reform in 2017. If they can pull it off, the historic legacies of Paul Ryan, Mitch McConnell, and Donald Trump are dramatically bolstered.

Finally, how to react personally, to upcoming tax reform?

If you are already a business owner, this is a thrilling tax reform proposal. Like seriously, chills and fist-bumps all around. By now you’ve probably already posted on Instagram with LOLOLOL OMG <3 <3 <3 Paul Ryan 4-Eva written in red lipstick font over a selfie of you in a bro-hug with your investors.

But if you are currently a salaried employee, what’s in this reform for you? Consider this: If you are a wage earner, rather than a business owner, the framework suggests you are basically doing it wrong. The current proposal to change so-called pass-through taxation of small businesses like LLCs and LPs from top rates like 35 percent to a top rate of 25 percent means that everybody (and their mother!) should earn money only through a business like an LLC or an LP, not through a salary paid by someone else.

But if you are currently a salaried employee, what’s in this reform for you? Consider this: If you are a wage earner, rather than a business owner, the framework suggests you are basically doing it wrong. The current proposal to change so-called pass-through taxation of small businesses like LLCs and LPs from top rates like 35 percent to a top rate of 25 percent means that everybody (and their mother!) should earn money only through a business like an LLC or an LP, not through a salary paid by someone else.

I, for example, need to stop charging money personally for my writing, and rather quickly open up “The Smart Money Business Columnist Thing LLC,” a financial opinions consultancy business, and sell my columns to the newspaper as a business service. My income tax rate could be a lot lower that way, under the latest proposal. You need to do the same.

The framework says vaguely that it “contemplates that the committees will adopt measures to prevent the recharacterization of personal income into business income,” but, well, we’ll see. In the meantime, wage earners, open up your LLC and become a business owner.

Please see related posts:

Adult Conversation about Income Tax Policy

Post read (224) times.