About two months ago the Trump Administration floated the idea of a new tax break on income from capital gains, requesting a review by the US Treasury of the idea.1 The tax break would in effect protect investors from having to pay capital gains taxes that result from inflation.

The response from the lamestream media – of which I am a proud member – was swift and condemnatory. “Unilateral Tax Cut for the Rich!” said the New York Times headline. “$100 billion tax cut for the rich” wrote Vox, and “Huge Windfall For The Richest 1%” said The Washington Post. The Times followed up with an Op-Ed questioning its legality, “Trump’s Crony Capitalists Plot a New Heist.”

As a general rule, I enjoy new income tax proposals. They’re fun and instructive. That doesn’t mean I think we should frequently enact new tax laws willy nilly. I just mean that, because taxes are the means by which government leaders most clearly enact their philosophy of what makes for a good society, tax proposals are a great way of figuring out what our leaders care about, and also what we care about.

In reviewing tax proposals, generally we should ask the following questions: Is it practical and enforceable? Does it reward or discourage economic behavior that we want? Is it fiscally prudent? Finally, is it fair? I’m interested in all these questions.

So how would the tax break work?

Capital gains occur when you buy an investment – a business, a stock, some real estate – and then sell that for a gain. If you made a profit of $100,000 on buying and selling your investment, the money you make gets taxed, generally at 20 percent, or $20,000. The proposal would allow you to avoid taxes on the portion of your gains attributable to inflation. But if inflation accounted for half of that $100,000 gain then under this new proposal you’d only owe taxes on half the gain, or $10,000. So yes, this represents a potentially big tax cut.

The tax cuts would be especially beneficial under two scenarios. First, if inflation is high, and second, if the investment is held over a long period of time, such that inflation accounts for a significant portion of the gains. One theory floated by proponents of the tax cut is that wealthy people holding highly appreciated stock, for example, would be motivated to sell if they faced a lower tax bill. Texas Representative Kevin Brady, Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee is reported to favor this reform, because “I think we ought to look at not penalizing Americans for inflation.”

Beyond those ideas, what’s the main case for this tax break? If you ascribe to the idea that investment and risk-taking is the engine of the economy, then rewarding risk-taking should lead to a more revved economic engine. Lower taxes might mean higher rates of investment, which should mean more economic growth. It’s a theory.

More than a theory, it’s an axiomatic beliefs of Republican leadership, currently in charge of the executive and legislative branches. These beliefs drove the tax changes of December 2017. Larry Kudlow, the top economic advisor to the White House, favors lowering capital gains through inflation-adjustment.

Is it legal?

Critics object to the idea that the US Treasury would enact this inflation-adjustment rule, rather than have Congress pass a tax reform law. Traditionally, constitutionally, the power of taxation resides with Congress. In practice however, the executive branch often leads the charge in proposing changes to tax laws.

What has taken some commentators by surprise is the Trump administration’s proposal that they enact the tax break through executive means. Hence the claims of illegality.

Smaller-scale capital gains on home ownership, small commercial properties, and small businesses – already benefit from targeted tax breaks and tax deferrals like homeowner exemptions and Section 1031 exchanges. Middle-class owners of stocks would tend to own them through tax-protected IRA and 401(k) retirement accounts. so would not pay capital gains taxes, and would not benefit from this change. This proposal seems specifically calibrated for larger-scale investments and the wealthiest taxpayers.

So is it fair?

This is where societal context matters the most, at least to me.

This proposal, theoretically sound or not, legal or not, smacks of class warfare from above. Here’s the context.

If we started from a relatively equal society then I’d be open to the theory of juicing investment through a targeted capital gains tax break. That’s not where we are.

The trend of the last 30 years has sharply increased inequality.

An estimated 65 percent of the gains from the 2017 tax law change will go to the top 20 percent of earners, who will benefit from the drop in corporate tax rates.

The Washington Post – citing a Wharton School study – found that 86 percent of the estimated $100 billion tax cut over the next 10 years would benefit the highest earning 0.1 percent of Americans, the top one-in-a-thousand wealthiest folks. $95 billion of the $100 billion tax cut would benefit the highest earning 5 percent of Americans. So, yeah, this tax cut overwhelmingly favors the people who are already well off.

We already have an income tax system that greatly favors “capital” over “labor.” What I mean by that is that if you are well off and primarily make money from your money – from investments in stocks, businesses or real estate – you generally pay a 20 percent tax rate on the money you make each year.

When you make money from your labor, however your tax rate increases with your salary but above about $50,000 your tax rate on labor will range between 22 and 37 percent.

Finally, can we afford it?

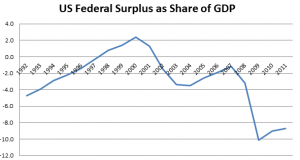

We are far from fiscally sound. The 2017 tax change is likely to increase the deficit by $1 trillion. By comparison, with a price tag of only $100 billion over ten years, this proposal is only a small bad thing, but definitely not a move in the right direction.

Post read (108) times.

- This week, President Trump floated the idea of yet another tax break, although Congress – the folks who write tax laws – claims it has no idea what he’s talking about ↩