With the announcement that MF Global Trustee (and former FBI chief) Louis J. Freeh will charge Jon Corzine for failing in his duty to oversee the company, the meaning of Jon Corzine shifts once again.

With the announcement that MF Global Trustee (and former FBI chief) Louis J. Freeh will charge Jon Corzine for failing in his duty to oversee the company, the meaning of Jon Corzine shifts once again.

Prior to this announcement, I understood the meaning of Corzine primarily through the following investment aphorism:[1]

“One of the worst things that can happen to you or a client is an early investment that wins big. You will become overconfident of your abilities and proceed to lose much more in the future through imprudent decisions than you initially made on the winner.”

Corzine’s career is the epitome of this wisdom, although he combined it with an uncanny ability to “fail upwards.” A few salient points in his timeline illustrate his pattern.

The 1994 failure in Goldman’s Fixed Income department

1. He made partner as a government bond trader in the ‘80s, and later managing Goldman’s entire bond trading operation, but Corzine ramped up fixed income risk just when the wrong moment hit.

Interest rates rose sharply in 1994, prompting a bloody massacre of fixed income departments on Wall Street, including an existential threat to Goldman’s survival, due to losses.[2] Instead of firing Corzine for his astonishing imprudence, the partnership felt it had no choice but to elevate Corzine to Chief Executive, all the better to unwind the level of risk in the fixed income department. His elevation illustrated another finance aphorism:[3]

“If you owe the bank $1,000., they own you. If you owe the bank $100 million, you own them.”

Corzine, as described in William Cohan’s Money and Power, How Goldman Sachs Came to Rule the World, in a sense ‘owned the bank,’ as the partnership could not afford to lose him due to its exposure to rising interest rates. He was a massive risk taker in the lead-up to 1994, making extraordinary money in 1992 and 1993. But when it all turned bad, instead of being fired, Corzine was rewarded with the top job at Goldman, paired with Hank Paulson to temper Corzine’s risk appetite.[4]

Summer of 1998, Long Term Capital Management, and Corzine’s attempted rogue portfolio trade

2. With the August 1998 Russian ruble-bond default and Solomon Brothers’ swap desk liquidation, most of Wall Street faced major exposure to the insolvent Long Term Capital Management, the first Too-Big-To-Fail hedge fund. The New York Federal Reserve attempted a private sector “bail-in,” requiring cooperation and an infusion of capital from each of the Wall Street firms, via a Godfather-style meeting of the families, hosted by the New York Fed.

Corzine, however, nearly managed to personally blow up the whole bail-in, achieving the rare trick of pissing off not only the rest of Wall Street but the entire Goldman partnership as well.

While the Fed urged cooperation between banks, Corzine attempted a sideswipe of the portfolio out from under the rest of the Street. He secretly negotiated a purchase of Long Term Capital’s entire portfolio using Goldman’s capital[5], presumably believing the firm could make a profit by taking on the risk of the illiquid trades.

This attempt, ultimately unsuccessful, came at a delicate time for financial markets, suffering unexpectedly large losses on Russia and exposure to LTCM.

Goldman, in particular, had been planning an IPO that Fall, which Corzine’s actions undermined. The IPO was delayed by market conditions, but also by the frightening style of rogue trading risk which Corzine engendered with his move. The firm leadership of Paulson, along with deputy heads John Thain and John Thornton, engineered a coup against Corzine’s leadership as a result.

Corzine seemingly never saw a risk he didn’t try to take, which ultimately proved too much for the partnership. They allowed him to stay nominally in charge through Goldman’s IPO in June 1999, with the understanding that Corzine would be professionally sidelined after that. His political career began shortly after.

MF Global and lack of risk controls

3. After unremarkable stints as Senator and Governor of New Jersey[6], Corzine landed the top job at MF Global, a medium-sized brokerage.

We now know Corzine continued his pattern of 1994 and 1998, in which he doubled-down and tripled-down on risks, in the face of extraordinary losses. Although his trading led to huge losses, somehow his ability to fail upwards did not derail his own personal career.

Up until MF Global became the eighth largest bankruptcy of all time, the meaning of Corzine seemed to be about his almost Forrest Gump-like success, in the face of amazing failure. His Midwestern affable, bearded, demeanor masked an unlimited appetite for investment risk. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t, but either way Corzine kept on moving upward.

We know in retrospect that Corzine’s pattern of unrelenting risk-taking continued at MF Global, and that ultimately some wrong-way bets on European sovereign bonds pushed the firm into chapter 11 bankruptcy.

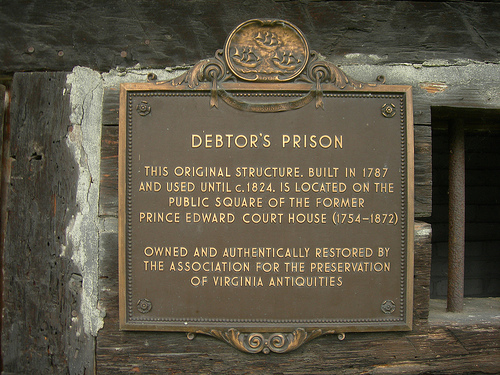

We also know some $1.6 Billion in customer funds were misplaced in the final days of MF Global, for which I’ve argued Corzine should be in jail.

A new meaning of Jon Corzine

Following the debacle of MF Global, and in the light of the 2008 credit crisis, however, Corzine’s career came to represent something darker and more insidious.

Unlike failed chief executives Dick Fuld of Lehman Brothers, or Jimmy Cayne of Bear Stearns, Corzine actually oversaw the misplacement of customer funds, not just the destruction of shareholder value.

We forgive – mostly – the leaders who drove their firms into the ground through errors in judgment, or risk management, like Fuld and Cayne. Shareholders lost, but shareholders took equity risk and our system rightly allows for losses like that.

Fuld and Cayne lost personal fortunes invested in their own firms, as they should have, and suffered for the loss in their reputation.[7]

But we should not forgive those who commit the fiduciary sin of misplacing customer funds, like Corzine.

I make a distinction between these so that we do not lose sight of the different types of losses, and the consequences. It bothered me, up until now, that Corzine was not pursued more aggressively for the loss of customer funds.

Too Big To Fail executives

For me, Corzine additionally offered the ultimate lie to the public about executive compensation. Namely, if you’re so essential to your business that you deserve, say, $12.1 million per year in good times,[8] how can you not retain the liability and responsibility when things go horribly wrong?

In what way did you earn the upside profitability, but not deserve the downside liability?

If you’re so good at what you do, then you need to be held personally liable when $1.6 Billion in customer funds go missing.

All of which is to say that I’m extremely pleased to see MF Global Trustee suing Corzine for his responsibility in the failure of his firm.

MF Global, the firm, was not Too-Big-To-Fail when it went under in September 2011.

Jon Corzine, the executive, until now represented a type of CEO who could earn profits and bonuses in the good years, without suffering personal consequences when things went wrong.

With the latest news, however, I’m encouraged that at least one Too-Big-To-Fail executive will suffer the consequences.

Please also see Arrest Jon Corzine Now

And Update on Jon Corzine by the MF Global Trustee

And One more rant on Jon Corzine

[1] All credit for this aphorism to financial planner David Hultstrom, whose ‘Ruminations on Being a Financial Professional’ is the best collection of pithy and wise investment advice I’ve ever seen collected in one place. See especially pages 9-12.

[2] Incidentally, I’m not in the prognostication business, but when you look at this simple chart of fixed income over the past 50 years, you see we’re at the very bottom of the rate cycle with very little to go from here. No risk manager alive has ever dealt with a massive move upward in rates, only short spurts in a secular move to lower rates. When the trend reverses, it will by U-G-L-Y.

[3] Attributed in different variations to John Paul Getty as well as John Maynard Keynes.

[4] I didn’t work in Goldman’s fixed income department until 1997, at which point Corzine ran the firm as senior partner, along with Hank Paulson from investment banking. Corzine was the bearded, affable, sweater-vest guy who would occasionally come down to the bond trading floor.

[5] Matched with capital from Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway.

[6] An associate of mine who dealt with Governor Corzine frequently complained about Corzine’s leadership in New Jersey. Although in agreement with his political persuasion, he found Corzine unwise politically and inconsistent to deal with.

[7] I actually wish we had more Japanese-style “begging of forgiveness” for corporate failure by chief executives. The promise of public shaming might help temper risk appetite.

[8] Corzine’s scheduled final executive package, before he wisely offered it back, in the wake of the Ch. 11 filing of MF Global.

Post read (5939) times.