At Bankers Anonymous, every day is a good day to be rational and get real.

But especially Pi Day!

Post read (7847) times.

Taking a break from commenting on Wall Street, the Dow’s highs and personal finance topics, I recorded a show yesterday with San Antonio, TX-based smart commentary site, Plaza de Armas.

A friend and fellow small finance business owner Shirley Gonzales announced her candidacy for San Antonio City Council, District 5. Shirley had previously introduced me to her Pawn Shop on a podcast, and explained the frustrations of trying to make something nice in her neighborhood.

On the video:

0:00 to 5:15 – Plaza de Armas Host Elaine Wolff and I speak about Gonzales’ candidacy.

5:45 to 12:25 – I share a coffee with Gonzales. She speaks about her vision for her district, zoning frustrations, and the most important day of her life, which had happened 2 days before.

13:15 – 17:50 Wolff, Plaza de Armas contributor Jade Esteban Estrada and I talk about the revitilization of downtown San Antonio, and I explain the most important real estate ‘Buy’ signal ever.

Post read (6588) times.

Please see my previous post New Highs in the Dow Part I – Indifference and Inevitability

The Dow is going to 36,000.

“What?” you say. “How could you make that prediction? How could you embrace the kind of crazy-headline-grabbing assertion that made fools of earlier market prognosticators? How dare you!”[1]

“You’re just shilling like all those other stock market bulls!”

Now wait a minute. How dare I?

Ok. You want to play games? You want to play rough?

Say hello to my little friend, “Compound Interest.” [2]

Remember the formula to convert today’s present value (PV) into tomorrow’s future value (FV), through an assumed annual return (Y) and a number of compounding years (N)?

FV = PV * (1+Y)N

If the Dow is roughly 14,000 today, it’s only a matter of time and an assumed annual return before we hit Dow 36,000. Or 21,000. Or 57,000.

I mean, seriously folks. Plug in an annual return and a time horizon, and I’ll tell you when we’re hitting that Dow target.

6% annual return, 14 years? Boom! Dow 21,000!

2% annual return, 6 years? Boom! Dow 15,700!

12% annual return, 17 years? Boom! Dow 96,000![3]

I mean, ultimately, who knows, and who cares?

But here’s what I do know:

Please see my previous post, New Highs in the Dow Part I – Indifference and Inevitability

And my next post New Highs in the Dow Part III – What should I do?

[1] Like these poor fools with their 1999 best seller: Dow 36,000: The New Strategy For Profiting From the Coming Rise in the Stock Market. And no, I haven’t read it and probably won’t, as again, it came out in 1999. Which made them look foolish. And yet also perhaps wise, as long as they allowed for a long enough time horizon.

[2] You’re supposed to imagine me saying all this with Al Pacino’s Cuban accent in Scarface.

[3] Admittedly, this last scenario isn’t likely. But if we get 10% annual inflation, a 12% return on stocks seems reasonable. And yes the returns will be largely nominal, with a huge reduction in purchasing power. But, hey! 96,000 Baby!

[4] Of course we should be empirical skeptics, cognizant of black swans in any particular scenario. Species-ending meteors do impact the Earth, periodically. So allocate 5% of your portfolio to Taleb’s Universa or whatever. But with 95% of your long-term investment capital, just try to do the simple, boring, thing. Trust me and embrace the sophistication that exists beyond complexity.

[5] In the short run (< 3 years), and possibly the medium run (5-10 years) risk-less assets beat stocks – occasionally. Not in the long run.

Post read (4015) times.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) hit an all-time high last week, an event as inevitable as it is fundamentally meaningless to everyone not currently employed by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, the owner of the Dow Jones & Co, inventor and keeper of the DJIA flame.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) hit an all-time high last week, an event as inevitable as it is fundamentally meaningless to everyone not currently employed by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, the owner of the Dow Jones & Co, inventor and keeper of the DJIA flame.

Remember, first of all, the Dow is a marketing tool

That is to say, I don’t blame the Wall Street Journal for crowing about a new arbitrary number on their Index, as the Dow is, after all, all about marketing. The Dow Jones’ upward move provides a marketing opportunity for the News Corporation’s media property and its media affiliates. No criticism there.

What is a shame, however, is that the plurality of the investing public who follow the market may not realize that the new high on the Dow means as much as an Onion article about

1. What really happened historically in the stock market,

2. What’s going to happen in the future, and

3. What you should do, investing-wise, about it.

Fortunately, you have your best friend, me, to give you the answers to these three questions, one at a time.

What really happened historically in the stock market

The recovery of broad stock indices to their previous highs of 2007 was inevitable, following the crash of 2008 and early 2009. I do not mean to claim that I could have told you at the lows of four years ago – March 2009 – whether the recovery of broad stock indices would happen by 2011 or 2015. Just like you, I had no idea, and I’m still agnostic about the short term direction of stocks now.[1]

What I really mean is that to assume anything other than inevitable growth in the nominal value of a broad stock index – over the medium to long run – is to assume a far-out scenario that has never yet occurred in modern times.

And to assume it’s anything other than inevitable is to place your tin hat firmly upon your pointy head and shut down your sensory gatherers to the data inputs of real life.

In the past one hundred years we’ve seen two World Wars, Depressions, small recessions, Great Recessions, Holocausts, Genocides, Earthquakes, Tsunamis, and the rise of Renée Zellweger as a bona fide movie star. Any one of these alone should have been enough to knock the equity markets permanently sideways, if such a thing were possible.

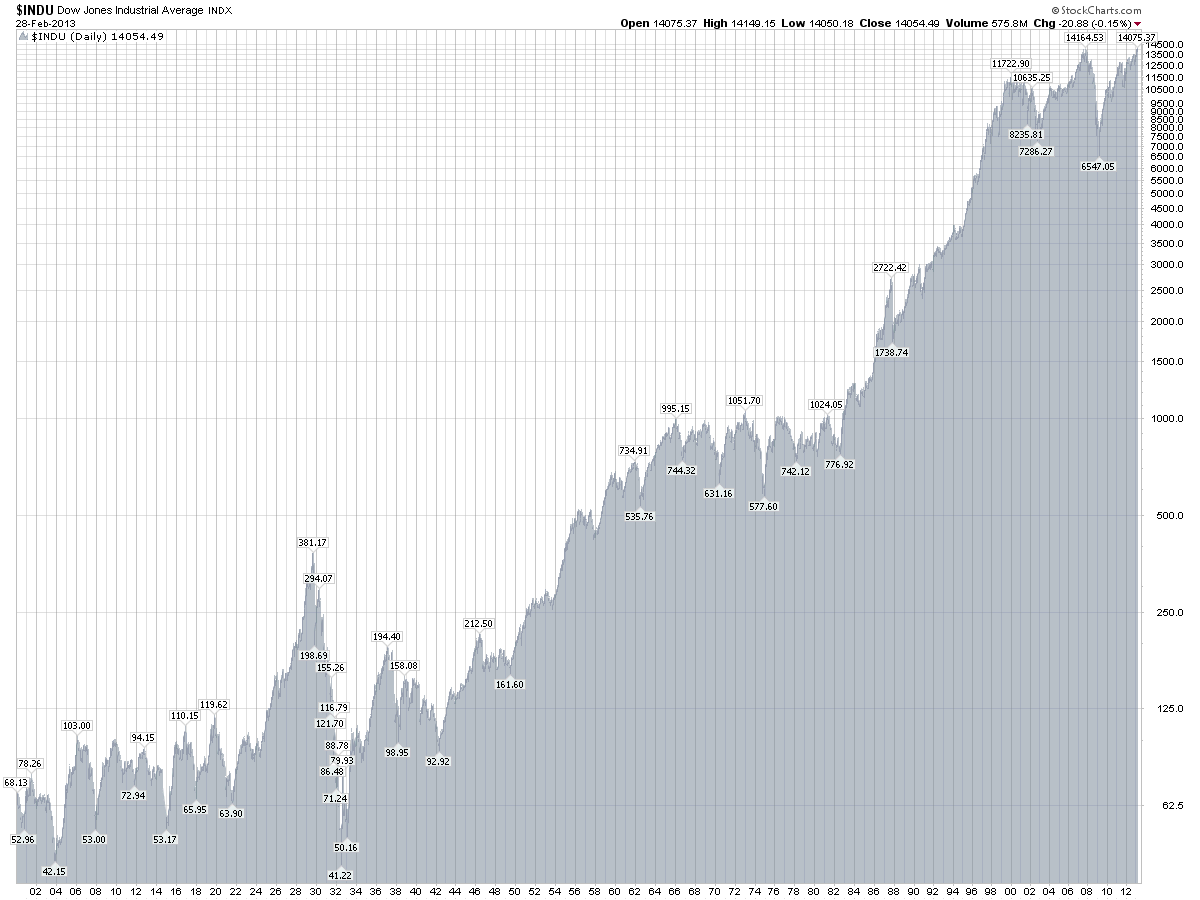

The fact is all of these occurred and the Dow moved from a high of 94 in 1913 to break new highs above 14,254 last week, one hundred years later.

The point is not to notice the new highs – although that’s what the Financial Infotainment Industrial Complex wants us to notice – but rather to notice that an index proxy for large stocks returned 15,000%[2] over a period of just a hundred years.

To choose a shorter 40 year time-frame – approximately the investing lifetime of today’s retirees – equity indices like the Dow nominally returned over 1,400%+ in that stretch. A stretch that included the tail end of Vietnam, Mid-East energy crises, Stagflation, the Cold War, 9/11, two Mid-East Wars, two separate decades of treading-water equity markets (1972-1982, 2000-2010), and of course the rise of Justin Bieber.

Any of those events alone appeared at the time to be reasons to sell and take all of one’s money away from any type of risky equities, or so the Financial Infotainment Industrial Complex would have us believe at the time. Throughout the last 40 years, the Dow moved from 900 to above 14,000. The lesson: It’s awfully hard to keep a diverse pool of public market corporations down for very long.

Like I said, I have no idea what’s happening in the short run and medium run, and I really don’t care. I also have no particular strongly held belief in any one company or any one industry, as I’m really not a stock market guy at all. In the long run, however, I know the rise of broad market equity indices to be inevitable.

Please see the next related post:

New Highs in the Dow Part II – What’s going to happen in the future?

and

New Highs in the Dow Part III – What should I do about it?

Also – This logorithmically adjusted picture of the DJIA since 1900 is cool. Clicking on it allows you to see it in all its glory.

[1] Although it was clear enough just a few months ago that base-case momentum would likely lead us to some medium-term ‘recovery’ mode, which made me lament, in anticipation, the passing of the Great Recession.

[2] Or 150X your original amount, depending on how you like your percentage-growth-over-time presented.

Post read (9471) times.

Even so, I made my students in my Personal Finance course keep track of their expenses for three weeks. Not necessarily to torture them, but because they might need it later on.

I don’t keep one, so I’m not about to suggest that that everyone else needs to start writing down all their purchases, packing those little flimsy receipts into their wallets and stressing until every last purchase gets recorded into their personal accounting software.

Since I don’t keep one myself, I hesitate to suggest it for others.

And yet, if debt is a problem, you might need it.

The Observer Effect

The “Observer Effect” from physics explains is why you should budget expenses every month if you’re having trouble getting out of debt.

The Observer Effect is often described in shorthand as the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principal,[1] although I recently learned these are different, frequently conflated, phenomena.

Quantum theory posits that the act of observation influences electrons in spatial relationship with other particles.

In other words, to look at an electron is to alter either its position or its momentum. Which kind of leads to messed up science.

Messed-up Science

But messed-up science can be our friend in personal finance.

To take a more common personal situation than quantum physics, doctors who study effective weight-loss techniques struggle with the basic scientific problem of Observer Effect. Essentially, when you enroll people in a study to observe weight loss effectiveness, you more often than not change the behavior of the people in the study.

Consciously or not, study subjects begin to consider more carefully their behavior and its effect on their weight. Whether you’re enrolled in the ‘control’ or the ‘study’ group, you no longer act or think precisely the way you did before enrollment.

Personal budgeting is a way to take advantage of this observer effect, if you have trouble coving your costs on a monthly basis.

We can use the observer effect to our advantage, altering our behavior in the act of observing it.

How I use the Observer Effect in my own life

I don’t carry monthly credit card debt, which is my primary excuse for not doing personal budgeting.[2] Frankly, my behavior when it comes to monthly expenses is fine already. Because I’m cheap.

But I periodically struggle with two other problems: time management – and keeping to a regular exercise schedule. I already know the ‘right answers’ when it comes to these behaviors, but knowing the right answers is not the same thing as doing the right thing on a monthly basis

Hence, the observer effect.

When I get really stuck, I’ve learned I can track either of these behaviors in a spreadsheet. Do I think I run four times a week but really I only run twice a week? Do I think I go the local gym twice a week but really it’s twice a month?

Am I wasting two hours a day surfing Facebook, clicking ‘like’ on Gawker articles? When I track every half hour of my day, I can begin to see that a scheduled twenty minute conference call actually eats up an hour and a half, between preparation time, and follow up emails, and daydreaming about what I should have said during the call.[3]

This tracking inevitably changes my exercise and time management behavior, subtly altering it for the better.

Look, I know it’s not a permanent change, and it’s not a cure-all. But it’s a start – and better than doing nothing.

A very successful business leader once told me the hardest part of his business is enacting adult behavior change.

I’ve learned over time that personal habits – especially personal habits we’re not proud of – rarely survive wholly intact after exposure to close observation.

All of which is to say if you have a hard time covering your expenses on a month-to-month basis – try budgeting.

[1] Apparently the ‘Uncertainty Principal’ describes the difficulty of simultaneously measuring paired properties in particles like electrons – such as location and momentum. The ‘Observer Effect’ with which it is often confused describes the problem of observing certain phenomena without changing the measured phenomena in the act of observation.

[2] My secondary excuse? Laziness.

[3] Here’s the best time-management book I’ve ever read, 168 hours: You Have More Time Than You Think by Laura Vanderkam. Also, she provides a handy spreadsheet that you can use to track your time.

Post read (4972) times.

I sat down yesterday for a conversation over coffee with Elaine Wolff, the Editor and Founder of Plaza de Armas, a smart, San Antonio-based news and commentary site.

We covered the Forbes Billionaire list, my recent review of Chrystia Freeland’s Book Plutocrats, elite legitimacy, and the profitability of new media.

The conversation starts at 59:40 and runs to 1:11:42

Post read (6507) times.