This is a continuation of a theme started earlier, in this post On Entrepreneurship, Part I

This is a continuation of a theme started earlier, in this post On Entrepreneurship, Part I

Founding an investment firm

A friend from college once explained to me that, growing up, he didn’t realize his family was wealthy. His dad worked at an investment firm, and they had a comfortable lifestyle, but my friend noted no major extravagances about their life.

One day his father told him that he had in fact founded the investment company where he worked, and that while the salary he’d drawn for the past thirty years had made them comfortable, their family’s real net worth, as he approached retirement, was something much more significant.

The key, his dad explained, was that unlike other dads who worked for a salary and then retired after a few decades, he had, by contrast, built up something very valuable at the end – his equity in the firm he founded. He sold the majority of his investment business to a European bank for a considerable sum, which overwhelmed the regular salary he’d drawn over the years. Being an owner made all the difference.

Suddenly my friend realized his family was more than just comfortable, it was inter-generationally wealthy.

The Goldman IPO

In my own life, I joined Goldman Sachs shortly before the firm went public via an IPO. This event made hardly any difference to my career or net worth. As an analyst with very little service to the firm at the time, I hardly rated any notable equity gift.

For people with longer service at the firm, however the lesson of the IPO – in particular the difference between fixed income and equity – couldn’t have been any starker.

Managing Directors, the penultimate ‘rank’ at the firm, could expect a low seven-figure payout through the IPO award of stock and stock options. That was nice, and I’d be the last one to ever feel bad for a Managing Director at Goldman.

Partners, the highest rank at Goldman, owned the firm before the IPO. I estimate Partners generally received a payout 30 times higher than Managing Directors at the IPO. Amazing to me.

The Managing Director IPO amount was cool and comfortable, but probably didn’t change everything about the person’s life. The 30-times-higher partner payout, represented blow-your-doors-off-never-work-again type money. All because the partners owned equity, and the MD’s didn’t.

Managing Directors and Partners did the same jobs, worked themselves to the bone the same way, dedicated their every waking breath to advancing the firm, and had distinguished themselves at the top of the financial pyramid. Usually the biggest difference between an MD today and Partner tomorrow was time – the Partners had typically joined the firm a couple of years earlier.

Although the Goldman IPO represented the extreme example of salary vs. ownership in my own life, I have come to think that that ratio holds true elsewhere as well.

My best guess is that the difference between fixed income and equity, when it comes to getting rewarded financially after a lifetime of building equity, is about 30 times higher.

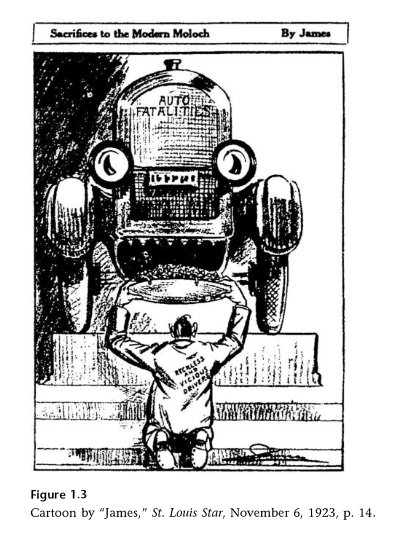

You know those charts showing the difference between fixed income and equity returns over the long run? I’m talking about charts where the returns from fixed income assets show a modest, steady rise due to moderate compounding effects, while the equity chart shows a rocky, but ultimately asymptotic upward turn?

Those charts show the difference in investment returns from bonds vs. stocks. And also the returns from working for a salary vs. owning and building a successful business.

I’m not insisting you be profit-oriented. But if you are profit-oriented, you need to figure out a way to own your own business. For the same amount of work, the financial payout is 30 times higher at the end of your career.

Caveats, qualifiers, clarifications on the for-profit life vs. other choices

Not everyone wants to work for profit, and I think that’s just fine. Great even.

Many people prefer to create beauty in the world, or to contribute to better understanding in human relationships, or to encourage the care and feeding of the soul.

Others seek to push the envelope on human knowledge, or to sculpt young minds, or to comfort the grieved or heal the stricken.

Others, perhaps a majority of the human race, just want to take in enough money on a weekly basis to allow some leisure time for beer, ice cream, and football.

I applaud you if you seek any of these things.

All of these goals, in their own way, are as valid, or more valid, than maximizing your pile of money.

So when I write about the advantages of entrepreneurship for maximizing personal profits, I’m addressing the profit-oriented person right now.

If you do plan to work on increasing your personal pile of money, you cannot afford to work for a salary, for someone else, on a fixed income. You need to start building equity, like, right now.

See previous post on Entrepreneurship Part I – Equity is Ownership, Fixed income is Salary

and subsequent post on Entrepreneurship Part III – More differences between ownership and salary

Post read (9602) times.