Editor’s Note: A (shorter and less conversational) version of this post appeared earlier today in the San Antonio Express News.

An official from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) responded last week to disagree with my article two weeks ago in which I claimed that Secretary Julian Castro supported subprime lending, in his speech about HUD priorities September 16th.

An official from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) responded last week to disagree with my article two weeks ago in which I claimed that Secretary Julian Castro supported subprime lending, in his speech about HUD priorities September 16th.

We had a lovely chat.

What Castro said

What Castro actually said in his speech is the following:

“According to the Urban Institute, the average credit score for loans sold to GSEs [*which stands for ‘government sponsored entities,’ shorthand for Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Federal home loan banks] this year is roughly 750. Currently, there are 13 million people with credit scores ranging from 580 to 680. Many of them are ready to own, but are being left out in the cold. The truth is that the dream of homeownership is out of reach for too many Americans. This has to change.”

I interpreted ‘this has to change’ to mean he advocated greater subprime lending. Castro specifically included credit scores that meet the ‘subprime’ definition, even though he did not use the phrase ‘subprime lending,’ probably because after the 2008 crisis ‘subprime‘ became a dirty word.

Definition of subprime

Banks sort mortgage borrowers according to their FICO scores, a personal-credit score based on past borrower behavior.

A 720 score and above is considered “Prime.” A 680 FICO and below is considered “Subprime.” To fill out the middle part of the scale, a 680 to 720 score is generally considered “Alt-A,” an in-between designation of credit worthiness.

Reasonable people can quibble on the exact FICO boundaries between Prime, Alt-A, and Sub-Prime, and banks can make their own determinations of the ranges for their own lending purposes, but 680 and 720 are the traditional boundaries separating the three segments of the mortgage market.

To make the definition completely clear: If you have a 680 FICO or below, to name one FICO score Castro mentioned in his speech, you have a history of not paying some of your debts on time. If you have a FICO score closer to 580, to name the other score Castro mentioned, you have a history of not paying most of your debts on time.

There’s no other way to have a 580 to 680 FICO than to have missed debt payments.

This doesn’t mean you’re a bad person. Nor does it mean you should never own a home. It just means that your past payment behavior suggests elevated future risks of not being able pay for your debts, such as a mortgage.

Most importantly, with a FICO of 680 or below, you will only qualify for a subprime mortgage from your bank.

So that’s why I think I made the reasonable inference from Castro’s speech that “This has to change” indicated a government preference for more subprime lending.

“Fair Access”

The HUD official did not agree with my description.

When I pointed out to the HUD official that historically 20% of subprime borrowers get into payment trouble on their mortgages, the official said I should focus instead on the 80% of borrowers who do not get into trouble, the ones who pay their mortgages on time.

Shouldn’t those 80%, he argued with me, have ‘fair access’ to the dream of homeownership?

Yes, of course. Nobody could ever disagree that people should have ‘fair access.’

He argued with me that the point of HUD policy is to ‘remove the barriers’ to the 80% of borrowers with bad credit who will pay their mortgages on time.

Removing barriers also seems great to me.

The much more difficult task is to figure out what ‘fair’ means, and what ‘access’ means. And what are the lending barriers that HUD wants to remove when it comes to borrowers with FICO scores below 680?

I would argue, and I did to Castro’s colleague at HUD, that the focus on positive outcomes for the 80 percent of subprime borrowers who pay their mortgage on time kind of finesses the point, by shifting the conversation away from the other 20 percent who will not be able to pay their mortgage.

And, in my opinion, the point is whether federal government policy should put its thumb on the scale to increase access to a market in which 20 percent of borrowers could lose their home due to non-payment on their mortgage.

In the end, however, I should not have worried too much because I don’t think the policies advocated by Castro will do much.

Actual Policy

It turns out, according to both the official and the follow-up materials his office sent me, that what Castro and HUD mean by “this has to change” is something pretty mild.

They mean a three-part program of

1. Encouraging borrower counseling

2. Clarifying lending standards (with an updated FHA Handbook!)

3. Analyzing additional data on mortgage lenders and sample mortgages

That all seems reasonable. In addition, this isn’t going to open the floodgates to increased subprime lending anytime soon.

Which leads to an interesting – albeit convoluted – ‘lets-agree-to-disagree’ point between myself and the HUD official.

Whereas I don’t think HUD should encourage more subprime borrowing and he does, I don’t think the federal government’s policies will have much effect, and he does.

So we’re both happy. I guess?

We all do this

Let me shift away from using the words “Castro” and “HUD” and “Federal Government” now to make this less personal, and frankly so it doesn’t seem like I’m politically attacking San Antonio’s golden child.

I’m going to make the decision-maker in the following sentences simply “We.”

Because I think we all do this.

As a society we are in the habit of wanting two contradictory things at the same time when it comes to banking policy, even though they are somewhat incompatible with each other.

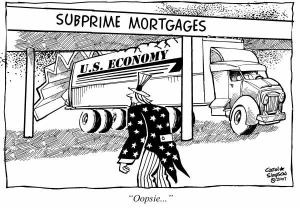

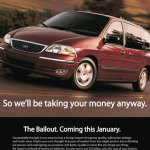

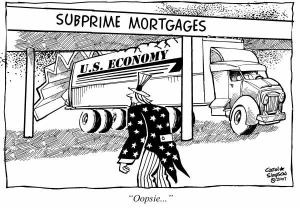

For equality-of-access reasons we want banks to lend to more people, especially the neediest people, despite the fact that such lending is historically quite risky for both the bank and the borrower. The borrower, who we want to help, can wind up without a home, in bankruptcy, and with further wrecked credit. Banks can lose money, which – when this happens systemically – can crater an economy, as happened in 2008. In these indirect ways, therefore, increased subprime lending is quite risky for society.

At the same time – or shortly thereafter, when 20% of these mortgage loans go bad, as expected – we want to punish banks for lending to the neediest people, “when the banks should have known better,” or when a loan to a needy person ends up looking predatory because either the rate is very high, or the collateral (the home) was seized in foreclosure, or both.

At the same time – or shortly thereafter, when 20% of these mortgage loans go bad, as expected – we want to punish banks for lending to the neediest people, “when the banks should have known better,” or when a loan to a needy person ends up looking predatory because either the rate is very high, or the collateral (the home) was seized in foreclosure, or both.

So we can all want these contradictory things at the same time, but I think we can also acknowledge that it’s all kind of hypocritical, no?

Please see related posts:

HUD Policy – The Good And Bad So Far

Mortgages Part VIII – The Cause of the 2008 Crisis

Mortgages Part V – Good Debt or Dangerous Drug?

Book Review of Edward Conard’s Unintended Consequences

Audio Interview Podcast – Mortgage Originator Explains the Crisis

Post read (19075) times.