In Part I, I discussed an internal Clinton-era memo in which US Treasury department officials considered the consequences of paying off our national debt, by 2012.

In Part I, I discussed an internal Clinton-era memo in which US Treasury department officials considered the consequences of paying off our national debt, by 2012.

The most frightening ironies of the ‘Life After Debt’ memo are the alternative vehicles the author proposed to replace US Treasuries.

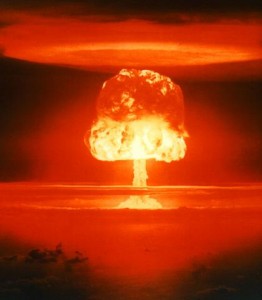

As a finance professional, reading the memo carefully, I almost chocked on my morning coffee at the proposals coming from the bowels of Treasury. It was like reading a 1930s memo proposing the invention of a nuclear bomb, as that would ensure the end of all future wars.

First, the author considers FNMA and FHLMC (more commonly known as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) agency debt as securities for the conduct of monetary policy instead of US Treasury debt. Since the companies were AAA-rated, fast-growing and as rock-solid as the US housing market (!), this was not an entirely crazy idea at the end of 2000. Obviously, with the receivership of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in 2008, we know in hindsight that a Federal Reserve balance sheet filled with agency debt would have meant a complete catastrophe wrapped in a shit sandwich. Although it had become an increasingly important staple of Wall Street bond issuance for the prior decade, agency debt from Fannie and Freddie became deeply distressed in the Summer of 2008, and would have ripped a limitless black hole in the Federal Reserve balance sheet. Needless to say it’s a good thing that did not happen.

But the second suggested vehicle for absorbing impending federal surpluses is the real problem. The author introduces “[N]ew, very low-risk securities constructed from a pool of private debt securities.”

Knowing what we know now, we should be thankful this idea never took off. I’ll quote the memo for a fuller description and then explain what the author was getting at:

Such securities would be packaged in a way similar to mortgage-based securities currently issued by Government Sponsored Enterprises like Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, but would not be as liquidity constrained and would be better diversified against certain market risks. To package the new instrument, a financial institution could buy a set of high-quality corporate bonds. It would then offer to sell a coupon bond called the Triple-A Plus bond that pays a fixed annual interest rate for the life of the bond. The Triple-A Plus Fund would put up its equity capital and take on the default risk of the underlying corporate bonds. Although not completely risk-free, bonds like the Triple-A Plus bond would entail very little credit risk and would be close substitutes for Treasury securities. With the advent of such an instrument, liquid and transparent markets should develop, given the value of just such a low-risk security to both private markets and the Fed.

Now, I take great interest in the author’s plan, because it is both prescient, up-to-date for its time, and in hindsight, incredibly stupid. This theoretical super AAA bond was in the process of being perfected by Wall Street at the time of his writing. It would have been constructed by pooling a diversified portfolio of high quality corporate bonds, and then offering a fixed rate to the holder who takes on the very-low probability of default. My sense is the author must have heard of this financial innovation through a conversation with Wall Street structuring professionals, and he then attempted to apply it to solving the problem of what instrument the Fed could use for investments instead of US Treasurys.

The author is right that there was no liquidity constraint on this type of instrument, which is another way of saying, Wall Street could make in infinite amount of it. The author also correctly notes that “the value of such a low-risk[1] security to both private markets and the Fed” would lead to the creation of extraordinary amounts of this debt instrument. Finally, and most importantly, the author was also right that the assets were “not completely risk-free,” although plenty of quantitatively sophistical investors believed them to be risk-free up until the period of 2007 and 2008, when they were shown to be financial “weapons of mass destruction.” The “Super-senior” AAA CDO, comprised of a portfolio of low-risk corporate bonds, was a particular innovation of Goldman Sachs’ mortgage desk where I worked in the years following this memo.

AIG Financial Products (AIG FP) considered the “Super-senior AAA CDO assets riskless, and the income derived from it to be free money. It was precisely these instruments, described by the author at the Treasury department, perfected in the following years by Goldman Sachs to the specifications of its client AIG FP, that sent AIG into government receivership in 2008. We can be thankful again that the Federal Reserve didn’t buy these products from Wall Street, as attractive as they sounded in the memo.

Up Next: Life After Debt Part III – Check out the “Where Are They Now?” file

Post read (2246) times.

One Reply to “Life After Debt, Part II – Weapons Of Mass Destruction”