Editor’s Note: A version of this post appeared today in the San Antonio Express News:

A former student at Trinity sent me a Facebook message recently. He linked to an advertisement message for an investment advisory company that emphasized the importance of ‘rebalancing’ one’s investment portfolio every quarter or every year.

A former student at Trinity sent me a Facebook message recently. He linked to an advertisement message for an investment advisory company that emphasized the importance of ‘rebalancing’ one’s investment portfolio every quarter or every year.

I realized I had not taught that principal at Trinity in our personal finance course last Spring. When the link came in on Facebook with the simple query from my student: “What is rebalancing?” I thought “Uh-oh, I missed that one.”

To make it up to that student, as well as to anyone else who might have the same question, here’s the quick explanation of rebalancing.

Rebalancing is one of those investment things you should do regularly, like brushing your teeth (only less frequently) or going to your college reunion (only more frequently). Once a year rebalancing is fine.

The point of rebalancing is to avoid two big No-Nos of investing:

1. Overexposure to one particular type of risk; and

2. The “Buy-high, Sell-low” investment behavior that everybody unwittingly does.

I’ll illustrate the simplest form of rebalancing with an example, assuming you have just two types of investments in your portfolio: a stock mutual fund and a bond mutual fund.

Let’s say you and your investment advisor agreed that you needed the 60/40 allocation to stocks and bonds that 98.75 percent of all investment advisors inevitably urge on their clients.

[Quick aside: I totally disagree with this allocation, and I’m not an investment advisor, so for both reasons please don’t think I’m recommending this for you. In fact I wouldn’t recommend it for the vast majority of people, but that’s a whole other column – or series of columns to come – in the future.]

Ok, back to my example, which will happen to match up – by pure coincidence! – with how 98.75 percent of your investment advisors have set up your portfolio.]

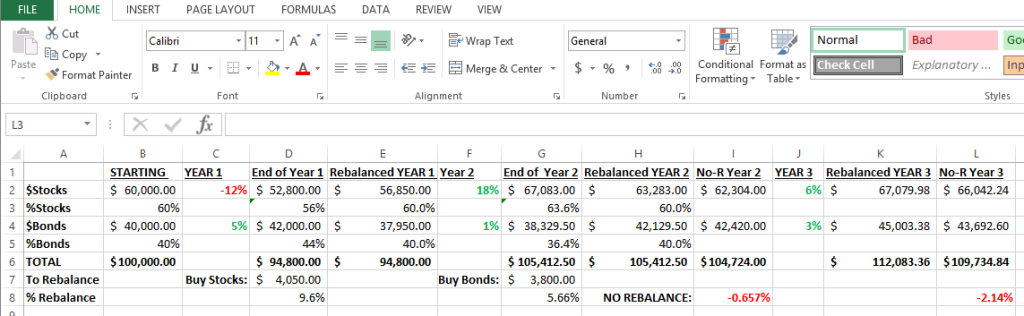

After one bad year in the stock market in our example here, let’s say stocks have dropped by 12 percent and bonds have returned a positive 5 percent, and now your portfolio allocation has shifted due to the market.

The new portfolio at the end of Year 1 now has a 56 percent stocks to 44 percent bonds allocation.

Here’s where the rebalancing part comes in.

When rebalancing at the end of the year you would sell some of your bonds – in my example 9.6% of your bond allocation so that it only makes up 40 percent of your portfolio again. With the proceeds of the bond sale you would purchase stocks, also returning stocks to just 60 percent of your portfolio. You would now begin Year 2 with your previously agreed-upon 60/40 asset allocation.

Next year, let’s say the stock market rebounds, returning a positive 18 percent, while bonds return just 1 percent overall.

Using numbers from my example, you end up with a 0.66% larger portfolio at the end of Year 2 through rebalancing. That may not seem like much, but those little amounts add up over time. If you have a $100,000 portfolio you would be $660 richer after just one rebalancing.

Let’s extend the example one more year. At the end of Year 2, before rebalancing, you have a 63.6% stocks and 36.4% bond mix. We’ll have to sell about 5.6 percent of our stocks to return to our preferred 60/40 mix.

In Year 3, let’s say stocks return a positive 8 percent and bonds return positive 3 percent. You will now have a portfolio 2.1% higher than if you had never rebalanced, or $2,100 on your original $100,000 portfolio. The math works in your favor this way with any asset allocation in which assets have different returns in different years. It also works just as well with more than two types of assets.

I’d like to list a few more important points about rebalancing, why it works, and also some caveats.

First, the act of regular rebalancing forces you to “Buy-low, Sell-high,” at least on a relative basis. Whichever asset class has outperformed the others will be the one you sell (high) and whichever asset class has underperformed will be the one you buy (low).

Second, while regular rebalancing makes sense, I doubt it makes sense to do this more than once a year. If you have a taxable account (a non-retirement account) then the tax costs of selling winners may outweigh the benefits. Also, frequent trading is always a mistake, so rebalance with moderation.

Third, because of point number two, if it’s possible for you, the best way to rebalance is not through selling existing investments, but rather through new investments. If you regularly contribute to an investment account, you can ‘rebalance’ your portfolio without tax consequences by simply purchasing more of whatever has become underweighted in your portfolio. This has the happy effect of allowing you to buy (relatively) low with your new investments, rather than to do what everybody else does, which is chase whatever hot sector has recently outperformed.

This may seem super-duper obvious and it is indeed super-duper easy to do.

But!

Most people don’t do it. After Year 1 of losing 12 percent in the stock market, for example, few people have the guts, rebalancing discipline, or a nudgy-enough financial advisor to remind them that their allocation is out of whack. Simple rebalancing will help correct that whack.

We get scared to buy something down 12 percent. After Year 2, we also have a hard time selling something that just soared 18 percent in a year. “Ride that winner!” we tell ourselves, to our later regret.

Post read (1510) times.

4 Replies to “Rebalancing, Explained”

How do you calculate how much you have to sell in order to rebalance in your examples?

thanks

Good question. I just used a spreadsheet to calculate each assumed change. Starting position, I assumed $100K portfolio, $60K stocks, $40K bonds. Then I assumed a market crash over the course of the first year, stocks -12%, bonds up 5%. Therefore, after Year One, Stocks = $52,800, Bonds = $42,000. In my simple example, To get back to our preferred 60/40 split, you have to sell 9.6% of your bond position, or $4050, and purchase stocks with the proceeds. Now you’re ‘neutral’ with respect to your preferred 60/40 allocation. I then repeated that process for assumed returns in Years 2 and 3. When you do that, and then compare to an un-rebalanced portfolio, you end up with more money through rebalancing. Not huge amounts, but something. Becuase they’re not huge amounts, you want to be cautious about both trading costs and taxes for any sales. Which is why I recommend rebalancing through new purchases, rather than actual sales, since purchases do not incur tax consequences. I’ve attached a screenshot of the spreadsheet I used to calculate amounts. Maybe you can follow along there? There’s no magic to the calculation, I was just taking simple percents of amounts, after assuming some annual return.

Your example only works if the two types of investments see-saw like in your calculation. However, if one class of investments, or a particular investment over a period of time out performs the others you will actually lose by rebalancing. The same if a particular investment of class of investments under performs. So, the benefits are very much situation dependent. I am not sure that the risks and costs and taxes really warrant this approach over the long term.

Well, I agree with you about costs and taxes being a mitigating factor.

In addition, I agree with your point about some class of investments outperforming another. For that same reason I don’t actually advocate a 60/40 split between stocks and bonds for a long term portfolio. For a long term portfolio instead I would advocate this: http://www.bankers-anonymous.com/blog/stocks-vs-bonds-the-probabilistic-answer/

But I use those as a simple example to illustrate just what rebalancing is.

Finally, I also agree with you (and, for example, with Warren Buffett) that diversification of risk (along with rebalancing) does not necessarily make you richer in the end. In fact, concentration of risk is the way to grow as fast as possible. However, diversification (along with rebalancing) can reduce both risk and volatility, if that’s your goal.