For people with resources to give for Hurricane Harvey relief, an important question has arisen this month: How do I decide where to give money? Among people who live in coastal Texas cities and towns, many donors probably already choose an organization they personally know, with a well-defined and limited mission, a local network of workers, and specific knowledge of affected communities. Think church groups, local food banks, self-organizing neighborhoods teams for clean-up and rebuilding, or local foundations.

For people with resources to give for Hurricane Harvey relief, an important question has arisen this month: How do I decide where to give money? Among people who live in coastal Texas cities and towns, many donors probably already choose an organization they personally know, with a well-defined and limited mission, a local network of workers, and specific knowledge of affected communities. Think church groups, local food banks, self-organizing neighborhoods teams for clean-up and rebuilding, or local foundations.

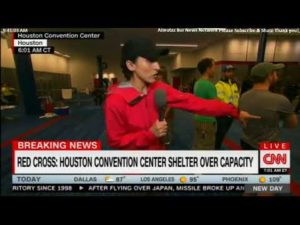

For Americans without specific ties to the area, however, the first recipient of giving is often the Red Cross. And the Red Cross, as the largest non-governmental disaster relief organization, has come in for special scrutiny in recent years, following natural disasters.

Pro Publica, a non-profit investigative journalism group, reported multiple times since 2014 on specific failings of the Red Cross, following disasters such as Hurricane Sandy and Hurricane Isaac in 2012, earthquake relief in Haiti, and floods in Louisiana in 2016.

One charitable interpretation of these reports is that, as the highest profile organization in any business that inevitably involves improvisation and mistakes – specifically, emergency disaster relief – the Red Cross becomes just the biggest target of criticism. Everybody makes mistakes in the midst of disaster, the thought goes, and bigger organizations make bigger mistakes and come in for bigger criticism.

A less charitable interpretation of the Pro Publica investigations is that there’s something inherently worse about the Red Cross than other, smaller, relief groups. A summary critique from Pro Publica is that there’s a lot public relations “show” from the Red Cross instead of a lot of actual relief on the ground, in these past disasters.

If you haven’t read the Pro Publica investigative reports from 2014 and 2015, well, they are scathing. Their deep investigations include a trove of internal documents produced by the Red Cross itself, which were also damning.

If you haven’t read the Pro Publica investigative reports from 2014 and 2015, well, they are scathing. Their deep investigations include a trove of internal documents produced by the Red Cross itself, which were also damning.

After Hurricane Sandy, for example, there was the deployment of 40% of emergency response vehicles to non-critical areas, in order to make them visible during press conferences on Staten Island. After Hurricane Isaac, a Red Cross truck driver reported being told to drove around the affected areas specifically to give the appearance of activity, but with no particular mission beyond public relations. There was the deployment of volunteers into the post-Sandy disaster who themselves were not fit enough to accomplish physically demanding tasks. In Haiti, Pro Publica reported in 2015, the Red Cross raised half a billion dollars to build housing after a devastating earthquake, but only 6 houses ever got built.

Less systemically, but still indicating ham-handedness, there was the truck full of pork lunches delivered to the Jewish retirement-community high rise in New Jersey after Sandy.

One of the recurring arguments in the ongoing aftermath of reporting on the Red Cross and other relief charities is what percentage of an annual budget gets dedicated to “programs” (the actual relief effort delivery) versus ”overhead,” or organization costs. The Red Cross self-reports that 91 percent of its $2.7 billion in 2016 went to programs, with only 9 percent dedicated to overhead, and that figure represents its typical spending in other years as well.

The non-profit reporting group Charity Navigator gives the Red Cross a respectable three out of four stars on their scale, for a combination of financial efficiency as well as transparency. Pro Publica itself challenges the 9 percent overhead figures, however, citing sub-contracting relief work to other organizations, which tack on their own administrative overhead costs, and thus obscuring the issue.

The larger point may not be arguing over what precise level of overhead costs is appropriate for what organization or what mission. Reasonable people could disagree on these issues. The larger point is probably whether they fulfill a needed role, at a crucial time, better than anyone else.

And maybe for a high-profile organization like the Red Cross, the key is whether they respond to past criticism by improving their delivery of services in the wake of Hurricane Harvey. Do they inarguably succeed at providing the best relief instead of the best public relations efforts? Time will tell.

I don’t even think that all public relations efforts are bad. In the last few weeks we’ve all watched elected public officials and other high-profile personalities conspicuously “helping” in front of cameras during post-Harvey relief, and this “help” is both an obvious public relations ploy but also an important show of societal solidarity. Healing includes seeing our leaders see the pain and chaos directly, and us believing that at some level our leaders “get it.” We accept a certain amount of show, to go along with the actual work, among government leaders.

With a non-governmental relief group like the Red Cross, however, maybe we expect a higher ratio of actual help to public relations show, since their role is less a symbol of our collective society and more about just delivering results? I don’t know exactly what’s fair.

When I dropped a few bucks into the collection bowl at my CrossFit gym to help send a fellow gym-buddy with his food truck to the Texas coast to provide hot meals, I expected a certain amateurish approach, producing a limited impact with our limited resources. If I elect to send money to a huge professional organization like the Red Cross, I expect an almost militaristic deployment, efficiently solving huge needs with their vast resources.

Right now, given all the immediate needs, all help is appreciated without an overly critical eye on “efficiency.” But as the post-Harvey recovery stretches into months and then years, we’ll need an assessment of which large groups delivered best on their promise of disaster relief.

It’s probably too early to assess, just two weeks after Hurricane Harvey passed through the region, to know which organizations made the biggest impact and which organizations did not. A natural question we will want to keep asking ourselves, however, is who helped the most with our dollars, so that we know who to support now, and in the future.

It’s probably too early to assess, just two weeks after Hurricane Harvey passed through the region, to know which organizations made the biggest impact and which organizations did not. A natural question we will want to keep asking ourselves, however, is who helped the most with our dollars, so that we know who to support now, and in the future.

Post read (351) times.

One Reply to “The Red Cross And Other Disasters”

I listened to a great podcast on charities and the overhead ratio. Podcast conclusion: 1) charities should be measured on lives affected, and 2) if a charity hires a $250,000 CFO, it’s reasonable to expect that he/she will do a lot more for the mission than a $75,000 controller with an inflated title.