I’m traveling with my family for the next month, so it’s summer reading time. Time to work on becoming less irrational.

I just finished reading Michael Lewis’ The Undoing Project,which tells story of the collaboration between Israeli psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman.

Tversky and Kahneman weren’t economists, but their collaboration begun fifty years ago subverted classical economics, and led subsequently to the rise of “behavioral economics.” Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 for their work; Tversky died a few years too early to share it with him.

Tversky and Kahneman weren’t economists, but their collaboration begun fifty years ago subverted classical economics, and led subsequently to the rise of “behavioral economics.” Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 for their work; Tversky died a few years too early to share it with him.

Classical economics starts with the basic assumption that people act rationally to maximize their own well-being. From that assumption, classical economists build a model of our world in which people and markets tend toward efficiency and self-correction.

Since the 1970s and increasingly in recent decades, behavioral economics built on Tversky and Kahneman’s ideas has shown we’re not particularly rational beings and markets can remain inefficient long past what we would expect.

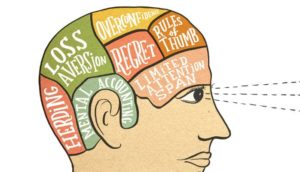

The psychologists pointed out some of our most glaring irrational human errors, now understood in shorthand by such labels as “anchoring bias,” “representative bias,” and “loss aversion.” The errors first showed up in mathematical or logical tests designed by the psychologists in which people not only made irrational choices but made them in predictable, clustered, ways.

Ever since these ideas became popularized, investors – both professional and personal – have sought to prevent being fooled by our own brains.

One partial solution is to study and teach probability and statistics. Another partial solution is to train ourselves to be skeptical of narratives that confirm what we’ve come to expect or that make the future conform to what we’ve observed in the past. As investors, we can struggle to recapture rationality by understanding our likely irrationality.

Part of what made Tversky and Kahneman so compelling is that they presented errors even among highly trained economists and statisticians.

Examples from their work, as presented by Lewis, illustrate applications for finance, business, and investing.

By “anchoring” we tend to attribute importance to numbers just because we see them first. The psychologists asked a group of students to estimate in their head the product of 8x7x6x5x4x3x2x1, and then compared them to a group estimating the same problem, but presented as 1x2x3x4x5x6x7x8. The group that started with the lower numbers first ended up with mathematical guesses only one-fourth as big as the group starting with the higher numbers.

I see this anchoring trick used in sales frequently. Like when the cleaning service salesperson came in to my house the other day, wrote down an outrageously high price, and then wrote a second number, about half of that, as the “special” price if I signed up this week. The high price, I’m pretty sure, had no actual meaning except that it made the special price seem unusually affordable. I saw this that day I submitted to a time-share pitch. You’ve probably experienced this anchoring bias at the car lot.

The bias of “representativeness” afflicts us by fooling us into quickly categorizing new things as if they resemble things we have already experienced. Houston basketball fans will appreciate “representativeness” in chapter one of The Undoing Project as Lewis delves into the mindset and methods of Rockets General Manager Daryl Morey.

Morey, more than any other executive, brought the “Moneyball” approach to the NBA, seeking market inefficiencies and statistical edges in drafting, recruiting and training basketball talent. Morey admits that the Rockets did not draft Taiwanese-American Jeremy Lin out of Harvard, despite the fact that he statistically “lit up our model,” probably because he did not look like what we expect in future NBA talent. Morey’s career is a study in the attempt to reduce this “representativeness” bias in building the team.Morey’s solution? Forbid basketball scouts and talent evaluators from making analogies with players of the same race. Somehow this reduces our tendency to assume physical resemblance or difference will lead to specific basketball results.

Morey, more than any other executive, brought the “Moneyball” approach to the NBA, seeking market inefficiencies and statistical edges in drafting, recruiting and training basketball talent. Morey admits that the Rockets did not draft Taiwanese-American Jeremy Lin out of Harvard, despite the fact that he statistically “lit up our model,” probably because he did not look like what we expect in future NBA talent. Morey’s career is a study in the attempt to reduce this “representativeness” bias in building the team.Morey’s solution? Forbid basketball scouts and talent evaluators from making analogies with players of the same race. Somehow this reduces our tendency to assume physical resemblance or difference will lead to specific basketball results.

More generally in finance and markets, when we see new data, we tend to fit it into a story that we’ve seen before or a narrative that already exists, and we fail to remain open to something we’ve never seen before. Thus, we’re often reacting to data based on the last bust or the last boom, rather than allowing the new information to suggest something new.

Finally, the “loss aversion” bias described by Tversky and Kahneman probably hurts our personal investment portfolio choices tremendously.

They tested and showed how emotional pain from a financial loss outweighed happiness from a financial gain, even in the same monetary amounts.

As Lewis points out in The Unwinding Project that it actually makes sense, from an evolutionary biology perspective, that we have this greater emotional response to pain than pleasure. In a tough survival-of-the-fittest evolutionary environment pleasure seekers, insensitive to pain, probably would die faster than pain avoiders.

From an investment perspective, however, this loss aversion can keep us poor. For me, this kind of insight into human irrational bias helps explain why so many individual investment portfolios built for the long run – such as retirement accounts – contain assets such as cash or bonds rather than higher-return stocks. We try to avoid the pain of loss more than we seek to experience the happiness of gain.

One important fact to know is that bonds have never outperformed stocks over a twenty-year period, in the last century. If you are a young person like me (fine, youngish!) with a retirement account built to last twenty years or more into the future, the choice of bonds in a retirement portfolio is really a choice that an extremely unlikely – never before experienced – thing is going to happen. It’s a choice – an irrational one – to bet on the lowest probability thing happening in the future.

Last week on the recommendation of a reader I checked out of a library the related book Nudgeby Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, which popularized the application of behavioral economics to policy. That’s up next on my list. What’s on your list for the summer?

All Bankers Anonymous Book Reviews In One Place!

Other books by Michael Lewis:

Post read (370) times.