Now that the holiday season is behind us, you’re probably wondering where to store all of your gold ingots, lumps of physical gold, and bars of gold bullion. The struggle is real, amirite?

Never fear, the State of Texas has your back, in 2018.

Never fear, the State of Texas has your back, in 2018.

Specifically, the Texas Bullion Depository wants to solve all your gold storage problems.

The Depository – created via legislation passed in 2015 and blessed by statute with the imprimatur of the Texas State Comptroller – is managed by a private company named Lone Star Tangible Assets. LSTA’s business affiliates also are in the business of selling gold, diamonds, and precious metals as well as offering storage services for investors and collectors, according to communications lead Josh Hinsdale.

The Depository is slated to open in January 2018, at which point they will publish rates for depositors. For now, Hinsdale told me, depository customers should expect the cost of a combination of storage and insurance will be less than ½ of 1% of the value stored, per year. Meaning, storing and insuring a $100,000 worth pile of gold bars should cost you less than $500 per year at the Depository.

Now, I don’t personally own any gold, for reasons I’ll explain further down, but it’s true that storing gold could be a problem for some Texans.

I called my homeowner’s insurance provider, and learned they explicitly exclude precious metals like gold in lump, bar, or sheet form from their homeowner’s policies. So, I could try to store gold in my closet or basement at home, but it would be with the knowledge that any losses, including theft, are at my own risk.

Another answer could be a safe-deposit box at my bank. I checked with my bank, and for $100 per year I could rent one of their larger boxes at their headquarters office in town. This would remove the gold problem from my house, and would afford me bank-level security. It would not, however, provide insurance against losses. The bank provides the space only, and unlike money deposits at the bank, my gold would get no guarantees against theft or destruction. I would need to purchase separate insurance for the value of my gold ingots.

The gold storage and insurance service, available in January 2018, is just phase one of the Texas Bullion Depository plans. Phase two involves the creation of a purpose-built facility for physical gold storage in Leander, Texas outside of Austin, slated for completion in December 2018. One of the points of phase two is to appeal to institutional investors, who may want a “Texas option” for storing their gold.

Now, the Texas Bullion Depository appears to be a thoughtful and serious service, and for people who need to store their personal gold, this seems better than the alternatives.

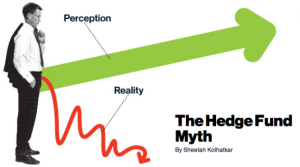

But here’s the more important thing I feel obligated to point out: nobody should be buying gold for their personal accounts. It’s not a wise use of your money.

Gold – unlike actual investments like stocks and bonds and real estate – produces no wealth or cash-flows. Unlike real money, it is too volatile to serve as a stable store of value. Unlike real money, it’s too bulky and inconvenient to serve as a convenient medium of exchange. Gold forms one of Mike’s Four Horsemen of Your Personal Financial Apocalypse, along with time-shares, variable annuities, and bitcoins.

I guess I could say the only thing gold has going for it is that it’s “better than bitcoin.” But frankly they are in the same genre of financial tricks played on the simultaneously gullible and paranoid. What I mean is that if gold is the Bozo The Clown of investments, bitcoin is Pennywise.

From previous reader feedback I already know I’m whistling into the wind with you gold enthusiasts, and likewise you can trust that your (undoubtedly, polite) disagreements will not tempt me to agree with you.

Given the precious metal fever-dreams to which gold-enthusiasts succumb, I think the state-sponsored part of the Texas Bullion Depository is odd.

The depository is, naturally, the only one of its kind in the United States. No other state has seen the need to create this through legislation.

The state Comptroller’s office released a video in December extolling the creation of the depository in Texas, noting:

“The Texas Bullion Depository will provide safe, fully-insured storage for precious metal, providing an alternative to depositories largely located in and around New York City.”

Something about the physical location of gold in New York apparently makes Texas lawmakers nervous?

“The law will repatriate $1 billion of gold bullion from New York to Texas,” Governor Greg Abbott’s office announced upon signing the bill to authorize the depository in 2015. I think using the word “secession” would be impolite here but I’m also not denying that’s the word that comes to my mind when I hear this kind of crazy talk.

The Texas Bullion Depository offers a legitimate solution to some people’s gold storage needs. Undoubtedly, however, this facility will also stoke more fringy gold-bug fantasies.

Now, do you mind if I share my own fantasies? I was disappointed to hear from Hinsdale there are no plans as of now for a “visiting room” to see the physical piles of gold once the facility in Leander gets built. I would totally take my girls on a field trip to visit big lumps of other people’s gold. Then we could spend the whole drive talking about how to stage an Oceans’ 11-style heist of the “Fort Knox of Texas.”

And really, what’s the point of a Texas Bullion Depository if it doesn’t inspire this kind of magical thinking? If Richard Linklater or Robert Rodriguez isn’t currently writing a “Goldfinger of Texas” screenplay starring the Wilson brothers then I demand a full refund for all of 2018.

And please see the related stories:

The Four Horsemen of Your Personal Financial Apocalypse:

Post read (435) times.