Let’s talk about the Presidential candidates’ worst economic ideas.

My preference when reading about presidential candidates is to focus less on the name-calling and memes, and more on their stated plans for improving the odds of positive economic outcomes for Americans during and after their administration.

When candidates propose something new, they should figure out if the policies would do more harm than good. Trump’s tariff plan, and Harris’ plan to fight food prices, each land somewhere between bad and catastrophic.

Trump’s Tariffs

Republican nominee for President Donald Trump has proposed a 10 percent tariff on all important goods from outside of the country, and a 60 percent tariff on all goods from China.

The stated purpose of these tariffs is to raise revenue that could replace other taxes such as income tax, plus protect domestic businesses and address a trade imbalance with China.

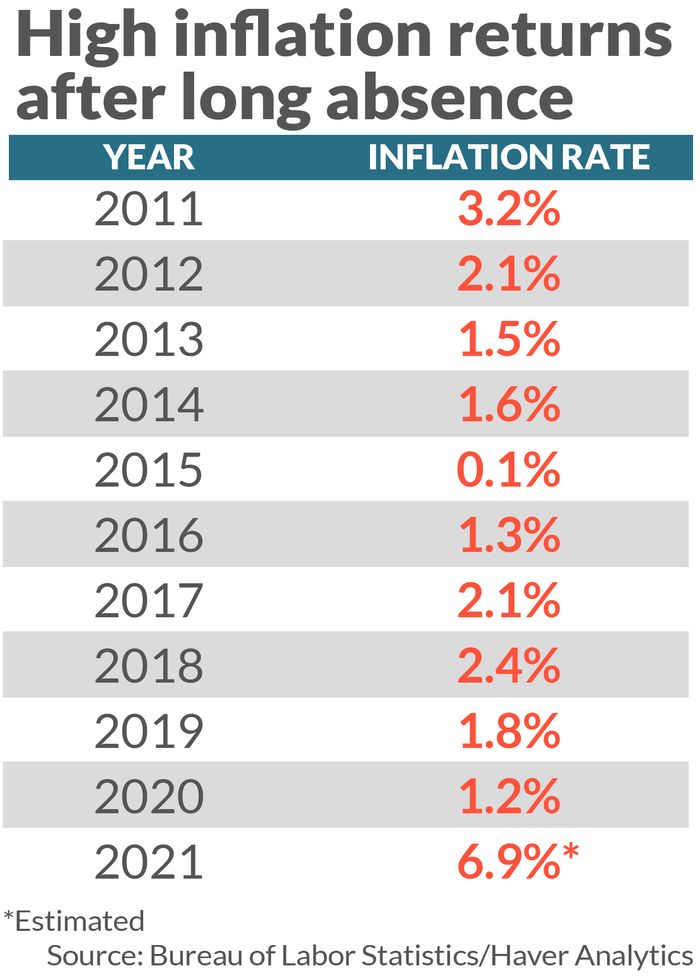

There is near-universal agreement among economists that even before a trade war – and indeed this would prompt a response from all trading partners and trading rivals – the tariffs would effectively raise prices on US consumers. This would kick off an immediate round of inflation and impose a $300 billion tax on the US economy, according to the Tax Foundation.

To the extent that tariffs boost domestic production, they would fail to raise revenue. To the extent they raised revenue, the price hikes would be felt by consumers as inflation. Domestic manufacturers that depend on intermediate goods produced outside the country would also pay higher prices and feel that same inflation.

That’s all very predictable even before we get to the secondary effects, such as the offshoring that our domestic manufacturers would do to avoid the 10 percent tariff. And the tertiary effects, which would be a Trump administration poised to “cut deals” and grant tariff exceptions to companies and industries that it favors for whatever reason, legitimate, political, or nefarious. The opportunities for corruption would multiply along with the bureaucratic barriers to trade.

To lend some nuance to my critique of Trump’s plan and the role of tariffs: Certain specific industries should get tariff protections or outright trade restrictions, plus domestic subsidies, if it is truly a matter of national security or the industry represents a key strategic chokepoint.

A consensus among economists has shifted over the past decade to recognize that protecting a domestic computer chip industry for example, or protecting our capacity for domestic military manufacturing, is necessary for national defense. But these industries are rare and strategic.

Trump’s impulse toward national strength and bolstering domestic manufacturing has led him too far and is deeply misguided. The effects of blanket 10 percent tariffs on importations would be catastrophic for consumers and for practically every medium and large business in the country. The inflation effects would be massive and permanent.

Harris’ War on Food Prices

In mid-August Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris unveiled a series of economic plans, the worst of which is an intention to fight “corporate price gouging” on food and groceries. Her plan did not come with specifics, but it’s nonsensical on its face.

To fight “price gouging” you have to be willing to impose “price controls.” And price controls will do more harm than good when it comes to food and groceries.

I don’t doubt Harris’ team poll-tested this idea and found it a winning argument among their likely or persuadable voters. But if so, their electorate is wrong.

Price controls involve monitoring for rule breaking. Price controls means regulators have to weigh in on the fairness of prices. Did the company raise its prices – on any number of (hundreds? thousands?) of grocery items for a legitimate or a non-legitimate reason? Who is to decide and how? You will need a massive and intrusive bureaucracy to police this.

Companies will then anticipate government intrusion, probably err on keeping prices artificially low in the short run to avoid penalties, and then pretty soon you would see scarcity on the shelves because keeping that grocery item stocked is a money loser. Consumers – all of us – could be catastrophically affected.

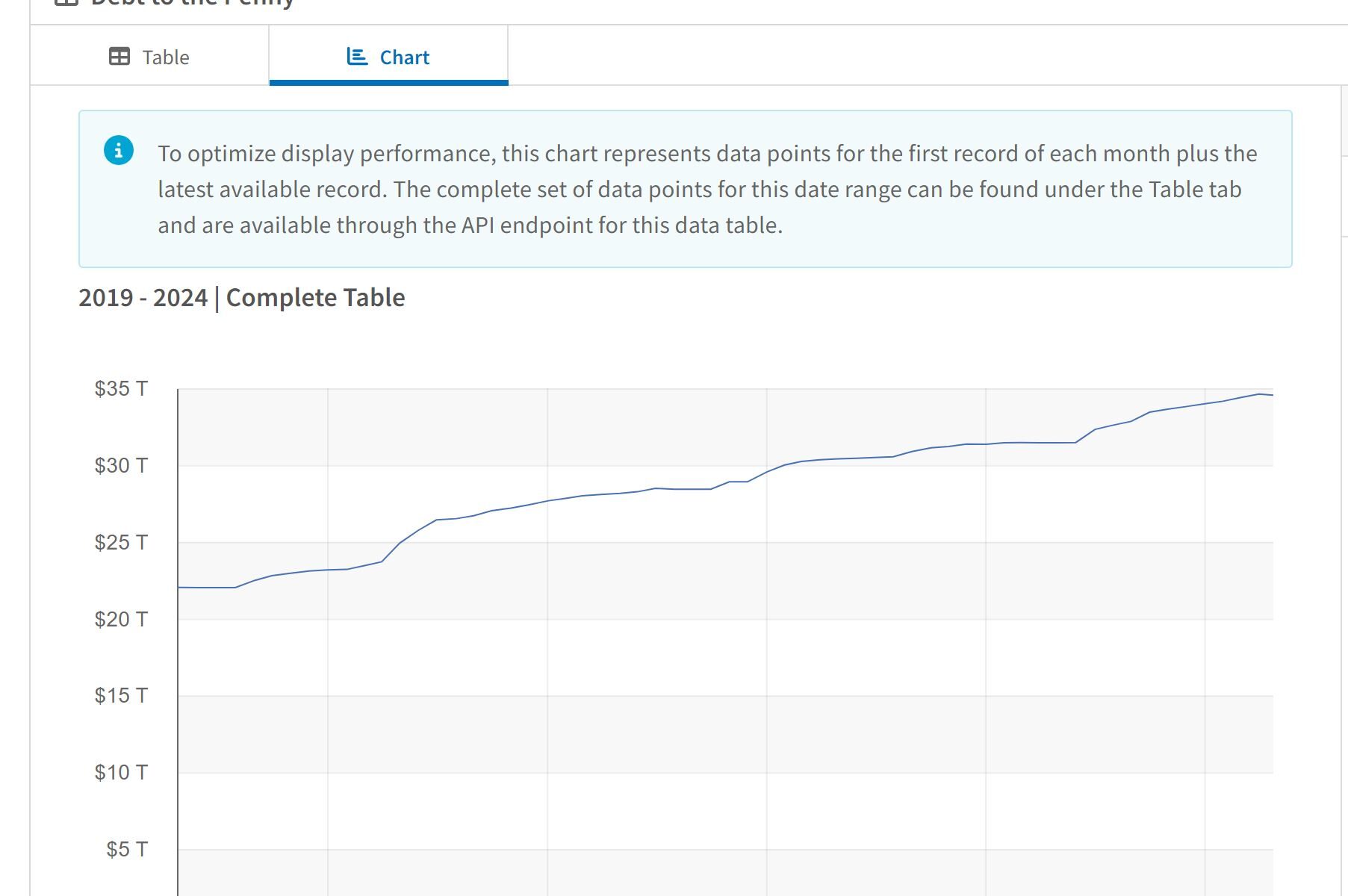

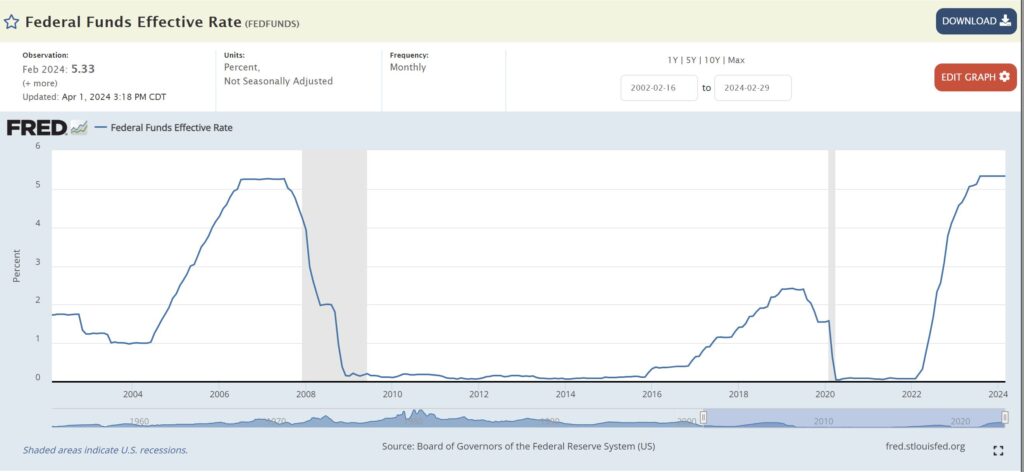

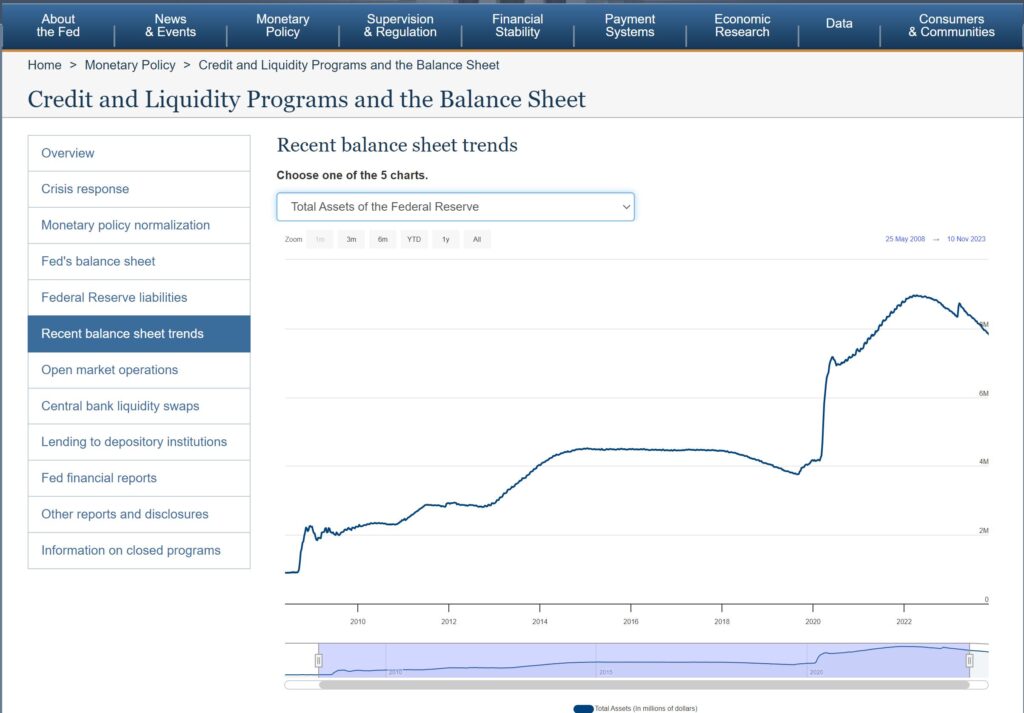

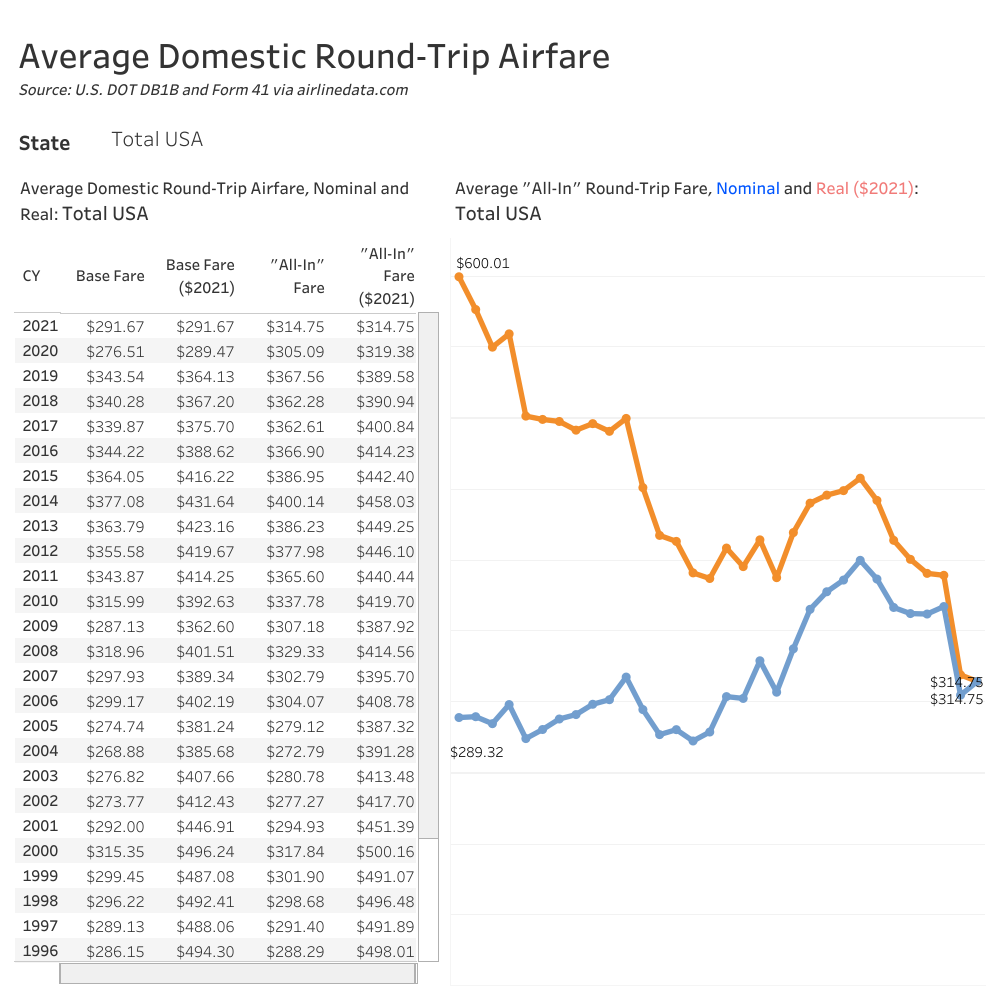

The goal of announcing a plan to fight “price gouging” is presumably to be seen as responsive to the very unpopular bout of inflation we experienced in 2022 and 2023. But there is literally no evidence that inflation is caused by mythical “greedflation” by corporations, and instead is caused by loose monetary policy, expansive fiscal policy, and corporations trying to adjust, survive, and thrive in a changing environment.

To take one salient example of price rises for a grocery item:

Two years ago the price of a dozen eggs briefly became an economic meme and supposed evidence for inflation and/or greedflation. It was a classic gross misunderstanding, or purposeful manipulation, of the story of how supply and demand works. An avian flu wiped out about 100 million egg-laying hens since early 2022. Once the flu receded, prices dropped in late 2023. They have recently risen again as avian flu outbreaks have recurred. But at no point in this fluctuating supply story would price controls have helped the situation. Lower prices for eggs imposed on grocery stores would simply discourage chicken farmers from reinvesting in rebuilding their flocks. Eggs will be plentiful and affordable again when the market gets back to equilibrium.

If you take the price-gouging idea and start believing price controls on consumer goods are the answer to the problem, then you’ve lost the thread. Slippery slope arguments are usually mistakes, but I’m going to acknowledge where our brains go with the slippery slope logic. You’ve already thought of the words “Venezuela” and “Cuba” before you read them here. Those countries have a lot of price controls and it’s not helping the average person’s standard of living.

Harris further offered support for “smaller food businesses” as part of a plan to bring down prices. The instinct for smaller obviously codes as a populist appeal against big business, but defies common sense. Any consumer knows that if you want the lowest prices, you’re going to Costco, Wal-Mart, or in Texas specifically, an HEB Plus-type store. Basically as big box as it gets. The Harris campaign probably knows that “Support your big box store!” is not an appealing electoral pitch, but is usually how we get lower prices in reality.

Smaller food suppliers usually correlates with higher prices. Micro suppliers like farmers markets will happily sell you a delicious $6 tomato – and that has its own aesthetic and ethical appeal – but most of us cannot afford buying in bulk at that kind of smaller-food business more than once in a while. I can’t really see how the federal government supporting smaller food businesses is moving us in the direction of lower food prices.

Like Trump’s tariffs, Harris’ focus on lowering food prices has a gut appeal (pardon the pun) but an obvious misunderstanding of how markets work in reality.

To return to the idea of price controls and to moderate my critique for a specific consumer sector, price-regulating of medications (by contrast with groceries) can be extremely important because

1. Pharmaceutical companies do hold legal monopolies (in the form of patents) so price-gouging in those markets can be a real thing, and

2. People buying life-saving drugs are truly vulnerable. Insulin is not a luxury good. Your expensive cancer treatment is not your consumer choice, it’s a life-saving necessity. These are complicated trade-offs but pharma is in a different category than highly competitive and substitutable markets like food and other groceries.

I hope the sophisticated advisors for our main Presidential candidates realize the folly of these populist proposals which defy common economic sense.

A version of this ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle

Post read (116) times.