Hey you, it’s April 12th. If you think the way I think (Let’s just make pretend together for a moment) you’re wondering how you’ll be able to fund your tax-advantaged individual IRA contribution for 2015 by Tax Day, Monday April 18th. Less than a week from now!

Hey you, it’s April 12th. If you think the way I think (Let’s just make pretend together for a moment) you’re wondering how you’ll be able to fund your tax-advantaged individual IRA contribution for 2015 by Tax Day, Monday April 18th. Less than a week from now!

Ideally, you’re like, “Ha, ha, no problem. I have that $5,500 maximum contribution right here in my savings account that my favorite blogger Michael wants me to put in. ($6,500 if you’re over 50!)”

But I can’t target this post for the both of you readers who actually scrimped and saved the $5,500 this year. I’m writing for the real, not the ideal.

Which means you should still make your contribution this week, and let’s vow together to do better next year.

But how do we do better next year? That’s the big problem.

Regular automatic transfers

The only technique I’ve ever believed in – when it comes to actually saving money for the purposes of investing – is regular automatic transfers.

Regular automatic transfers are why 401K investing works so well, because your money gets taken out of your paycheck and then invested without you getting your greedy little hands on it.

Regular automatic transfers are often why paying off a mortgage over 30 years can reliably build up middle-class wealth. You simply get in the habit of making your house payments automatically every month, and presto! Thirty years later you have an actual positive net worth via your house.

Regular automatic transfers are why new fintech solutions like Digit, Qapital, Dyme, Acorns, and Betterment all offer to slip little tiny bits of your forgettable change out of your bank account and into a savings or investment account, to at least kick-start your investing habit, or to help you pay down debt. I don’t use any of these services, but their regular automatic transfers game is on point.

$15 a day

On short notice – between now and the end of this week for example – could I come up with $5,500 to put into my IRA? Well if you put it that way, not really.

What about maybe monthly? Do I have an extra $458 per month, after paying for the kids’ needs, and eating out, and losing money at my weekly poker game with the neighborhood dads? (That’s the $5,500 maximum allowable IRA contribution divided by 12, but you knew that.) Who’s got that kind of money? So again, not really.

To get there, how about breaking $5,500 down into the smallest possible increment? Could I save up $15 per day?

I’ve written about the fact that my caffeine addiction already leads me to waste most of that amount of money on most days. Have you ever tracked your “indefensible” expenditures? How hard would it be to save $15 per day? Maybe pretty hard, but my guess is it’s only doable via regular automated transfers.

My bank

Inspired by that thought, I logged into my bank where I have both a checking account and a savings account.

I checked my bank’s transfer set-up online, and I saw I could program it to shift money from my checking account into my savings account once a week. I didn’t see an option for daily transfers, although ideally I’d do that instead.

Would I be able to handle an automated $105 per week transfer? (That’s $15 per day, but you knew that)

Something tells me I could. Something tells me that even though transferring $5,500 in early April each year might drive me crazy, the thought of transferring $15 a day (in weekly $105 increments) might be doable. So I set it up to do just that, for the next two years. Would you like to join me in this experiment?

Irrational behavior

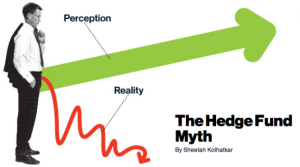

I’ll be the first to admit it, regular automatic transfers aren’t “rational,” in the sense that traditional economists assume we are rational people when it comes to money. Why should it matter if I’m moving money from one account to the other on a weekly basis, without affecting my overall net worth? It should not matter in the least. So this isn’t rational, but neither are we when it comes to money. We are all a little bit crazy when it comes to money.

Not for everyone

Another caveat. Regular automatic transfers out of a checking account into a savings account – or better yet, into an investment account outside the reach of your greedy little hands – won’t work for everyone. Some of us will raid that “sacred account” as soon as it accumulates a little bit of money. My only advice – if you think this will be a risk for you – is to make the destination account as difficult-to-access as possible.

Maybe try this: Write down your investment account password on a piece of paper, then rip that paper into tiny pieces. Now eat the bits of paper.

What? You don’t think that will work either? Forget it, sorry, it was just a thought. I guess we’re all irrational in different ways.

Please see related posts:

Ask an Ex-Banker: The Magical Roth IRA

Book Review: The Automatic Millionaire by David Bach

Post read (237) times.

On many an important point he acknowledges the unknowability or unprovability of his point. Nevertheless, not doing what he says – not intuiting the essential wisdom – leads to grievous error. You’re welcome to persist in your own stubborn views, he seems to say, and best of luck to you.

On many an important point he acknowledges the unknowability or unprovability of his point. Nevertheless, not doing what he says – not intuiting the essential wisdom – leads to grievous error. You’re welcome to persist in your own stubborn views, he seems to say, and best of luck to you.