A version of this appeared in the San Antonio Express News

Dear Michael,

I own a little of MO, purchased some time back with an average cost of $27.37. As you know it pays $2.08 dividend, and when I tell my friend my return is 8%, he says my return is what the stock presently pays, 3.8% or so.

I figure my return on my cost, not present price. Who is correct?

George, in Boerne, TX

Dear George,

Thanks for your question, which hinges on what we mean by ‘returns’ when we talk about an investment. And I can tell you who is right.

I will also use your question to discuss the unending debate between returns on stocks and returns on bonds.

Dividend Yield

Your friend’s definition of return at 3.8% posits a very particular number known as ‘dividend yield.’ We figure dividend yield mathematically by dividing the annual dividend of a stock by the current price of that stock.

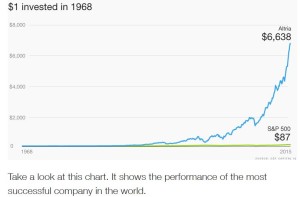

Since the stock MO (slightly more commonly known as Altria, more likely known as Phillip Morris, and best known as a massive purveyor of cigarettes such as the iconic Marlboro brand) pays $2.08 per share per year in dividends and currently trades around $55 per share, the dividend yield is roughly 3.8% – which is $2.08 divided by $55.

I know precisely zero people (like your friend) who would call 3.8% the ‘return’ on owning MO stock.

So he’s wrong.

Instead, the return of MO stock ownership is the calm satisfaction you get from funding a delicious and refreshing tobacco-smoking experience for millions of satisfied customers.

Haha just kidding, lolz, smoking is disgusting.

Annual vs. Overall Returns

Annual vs. Overall Returns

What I actually mean is the real return of MO stock ownership is calculated, as you already indicated, by figuring out your average purchase price, the current market price, and any dividends you may have received in the interim. Since your MO shares have doubled in price since you bought them, your overall return is something north of 100%, so far.

And so far, so good, for you.

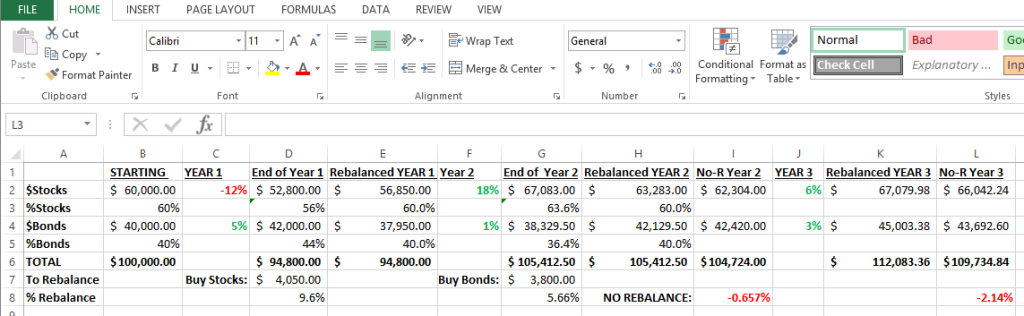

However, we frequently talk about ‘annual return’ on an investment rather than ‘overall return’. If you made this purchase nine or ten years ago, your annual return might be something like the 8% you stated.

But I don’t know. It depends partly on when you bought, and also how you did or did not reinvest dividends.

If you know your way around an Excel spreadsheet, I could use the ‘IRR’ function to input your various annual purchases, plus any interim dividend cashflows, and then the proceeds you would collect when you sell, in order to calculate your annual return.

Then you can tell your friend to put that number in his pipe and smoke it, so to speak.

It’s well above 3.8%.

Knowable vs. Unknowable returns

But since you haven’t sold MO, you don’t actually know yet what your total, or annual, returns will be on the stock. You have to sell the shares to know your return on any stock investment.

And that leads me to a thought on the psychological problem of investing in stocks, especially when compared to bonds.

Since you have to sell to know your return, and since the correct holding period for stocks is roughly ‘forever,’ stock returns are less knowable than bond returns.

Stock returns, unlike the returns on bonds, are unknowable ahead of time. You basically have to leap into the unknown with stocks, which you don’t have to do with bonds.

Unlike stocks, traditional bonds simply ‘mature’ after a set number of years and ‘return’ your money back to you in the fullest sense of the word. Because your money ‘returns’ to you with a bond at a set date, calculating bond returns is knowable.

Bond yields are, however, a bit mathematically complicated.

For simplicity’s sake, traditional bonds have a known ‘Coupon Yield’ which tracks the income an investor can reasonably expect just by holding the bond. This would be analogous to your ‘Dividend Yield’ that I described for stocks above.

The Coupon Yield is the ratio of the annual bond payments to the bond price, so a bond issued with a 3% annual coupon starts off with a Coupon Yield of 3%.

Sophisticated bond investors do not consider ‘Coupon Yield’ an accurate enough measure of bond returns, however.

Calculating bond yields

After a bond has been issued, the ‘annual return’ or ‘yield’ you get holding a bond depends on whether you paid more or less than face value for the bond. If you paid less you will make a higher return than the coupon, and if you paid more, you will earn a lower return than the coupon. A precise yield or return calculation would require applying a special ‘discounted cash flow’ math formula to all remaining bond payments.

Confused yet? That’s the way we finance people want to keep it!

Haha just kidding, lolz. Finance is disgusting.

Ok, no, it’s not disgusting, but I’d have to direct you to some math to learn more about calculating bond yields and ‘returns.’ Don’t worry though, because a main point is this: The final ‘returns’ of a traditional bond held to maturity are knowable, making bonds psychologically comfortable for some folks.

Final ‘returns’ on a stock depends on an average purchase price and average sale price. So until you sell the stock, you have unknown returns. This partly explains why stocks are psychologically uncomfortable for some folks.

Stocks v. bonds

So which one should you own in your investment portfolio?

Well, let’s see, that’s a complicated question with many answers.

Let me tap out the tobacco in my pipe, my young friend, clear my throat heartily, and tell you in a deep voice that it depends on your time horizon, your risk appetite, your savings rate, plus a sophisticated calculation regarding the number of years until your retirement.

Haha just kidding, lolz.

You should own stocks.

Please see related posts:

Another discounted cash flow example

Post read (1284) times.