Tell me: do you want the good news first, or the bad news? Fine, we’ll start with the bad news.

In 2022, USAA reported its first yearly “net income” loss since 1923 – the first loss in one hundred years! – of $1.3 billion.

Next, the CFO reported that the company’s own measure of its “net worth,” the difference basically between what it owns and what it owes, dropped dramatically from $40.1 billion to $27.4 billion from 2021 to 2022.

That’s a $12.7 billion drop in net worth, or a 31.6 percent drop year-over-year. Not great.

Finally, USAA had reported a line in its consolidated statements called “Other comprehensive income (loss), net of tax,” a loss of $10.5 billion. Since that was 8 times bigger than its “net income” loss, and roughly the size of its reported drop in “net worth” over the year, I reached out to the company to tell me what the heck “other comprehensive income (loss), net of tax” actually means. It’s not an accounting term with which I was previously familiar.

Brett Seybold, Corporate Treasurer, responded to my query. “The ‘other comprehensive income loss’ was due to unrealized losses in our investment portfolio across all lines of business, about half of which is in our bank. This is the result of lower market valuations from rising interest rates, which impacted the full financial services industry last year. It’s important to note that this accounting value change is temporary and has already improved in 2023 – and any undervalued securities can simply be held to maturity.”

This makes sense (in fact this was my best guess before Seybold confirmed it). It is also worth contextualizing his response with what’s happened lately with other banks.

The larger US banking context

The recent failure and seizures of First Republic Bank, SVB, and Signature Bank by the FDIC (the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th largest bank failures in US history, respectively) have bank customers (and regulators!) on edge a bit these days.

Listed as the largest Texas-headquartered bank by both assets and deposits, USAA carries a sort of flag for the industry in the state.

Unlike past eras of finance wobble, recent bank failures haven’t happened because of crazy risk-taking or irregular accounting or any number of traditionally morally questionable actions for which we might judge bank executives harshly.

Instead, a simple and simplified model of recent bank failures is this.

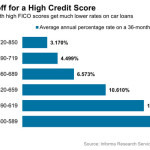

Step one is that banks like SVB held lots of super-safe assets like US Treasurys which lost their current market value when interest rates rose rapidly throughout 2022. Fixed income assets – the finance term for bonds and similar investments – drop in price as interest rates go up. As long as a bank still holds these super-safe assets and doesn’t sell them, the losses aren’t necessarily locked in. That’s what USAA’s Seybold confirmed made up what happened at USAA with the $10.5 billion loss under the line item “other comprehensive income (loss).” Roughly half the number for the bank portfolio, and half for the insurance portfolio.

The not-necessarily-market-value generally is not a problem because depositors don’t all ask for their money at once. These super-safe bonds will all pay out in full eventually. Regulators are cool with it too. Usually.

Step two with SVB, Signature, and First Republic Banks, however, was that they catered to customers who held large deposits, with a (now we understand to be an overly) large proportion above the FDIC-guaranteed $250 thousand threshold. Those large and relatively sophisticated depositors moved their accounts too rapidly for the banks to sell their assets in an orderly way. Because a significant portion of bank assets were actually worth less than their value on the books of the banks, and the withdrawals happened fast, the market value of the banks – roughly their “net worth” was wiped out just as they faced a liquidity crunch. So, we got FDIC receiverships and forced sales over a weekend for the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th largest bank failures in US history.

There were things these failed banks could have and should have done better, we now know in hindsight. Financial institutions can use interest rate swaps to hedge their declining bond values. They can underwrite or hold shorter-maturity assets that allow them to pivot more nimbly when interest rates rise. They can diversify away from an over-concentration on high-deposit customers, although that last move takes time, and for bank executives is probably counter-intuitive. (Banks generally love and want to attract high-deposit value customers!) But that’s all in hindsight for those particular banks.

What we should concentrate on are banks today. Specifically today, what should we think about USAA’s 2022 performance?

The Good News, or Why I’m Not Worried About USAA

Without insider insight into their fixed-income hedging strategies (although again in hindsight they maybe did not hedge rising rates enough in 2022) two things about USAA seem true, and comforting.

First, USAA is not simply a bank but a diversified financial services company. They are foremost a property and casualty insurance company, and also a life insurance company, and then also a bank. Insurance had its own specific 2022 problems like higher loss claims due to inflation and supply-chain bottlenecks. But in general, with 77 percent of annual revenues coming from insurance premiums, they operate in a different category than traditional banks. Insurance companies always run and manage risks, but bank runs aren’t really their main worry.

More broadly, their banking customer base is not primarily high-net worth individuals, but rather active or retired military personnel and their families. As Seybond confirmed, “Our bank is consumer based, 93% of deposits are within the applicable FDIC insurance limits, and we have access to excess liquidity to serve the needs of our members.”

I’m not at all worried about USAA personally as my bank, since I (sadly for me) do not have balances larger than the FDIC-guaranteed $250 thousand. Mo’ money, mo’ problems as the saying goes, and the inverse is also true when it comes to this specific consumer-banking risk: less money, less problems. Alas for me.

Maybe I should have mentioned, I bank with USAA. My checking, savings, credit card, home mortgage accounts, plus my kids’ bank accounts, are all with the company.

I insure with USAA as well: auto insurance, home insurance, and term life insurance.

I live in the hometown of their headquarters, and have many friends and acquaintances who work for USAA. I wish the company tremendous success but also I am self-interestedly curious about their setback years as well.

People are nervous right now about financial institutions. A once-in-a-hundred-year loss naturally prompts a question of whether it is anomalous bad luck or a trend. As the largest bank headquartered in Texas, USAA enhances public trust by explaining even the bad years when they occur. And even the obscure accounting lines when asked. I appreciate their letting me dig in a bit. Ninety-nine years before hitting a loss year is a pretty good track record.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Post read (149) times.