Editor’s note: Yeah Yeah Yeah I have the worst timing of all time. Still, the idea that this vehicle exists is important!

One of the regrets of my last ten years as a Northeasterner-turned-Texan is that I’ve only fulfilled some of the stereotypes.

To be fair to me, I’ve accomplished important ones. I wear Lucchese boots. I wear bespoke guayaberas – shout-out Dos Carolinas! I am not yet, however, an investor in oil and gas. I say this with some wistful regret. I want to fit in as a real Texan.

I have recently discovered a possible way to correct this – the subject of the rest of this column – but I should start with a few reasons why I haven’t yet invested in oil and gas. The most obvious reason is that I don’t have enough money to be invited into large-scale opportunities. Next, I have no particular expertise that would assist me in oil and gas investing. Prudence suggests – and I always suggest – doing the simplest, low-cost investing thing that requires the least amount of knowledge.

Oil and gas investments are famously opaque and high-cost opportunities – meaning if you buy into some heavily-promoted deal, it’s hard to avoid just funding a dry hole while paying many layers of fees to the operator or promoter, who makes money whether they are successful or not. The proverbial “heads you win, tails I lose,” kind of situation.

Having laid out some caveats – which hold true no matter what – I am intrigued by a Houston-based online platform called Energy Funders designed for the little guy (like me) to invest in oil and gas opportunities.

When you create an investor account on Energy Funders (as I did this month) you can access specific oil and gas exploration opportunities, with a minimum as small as $5,000. Garrett Corley, the VP of investor relations who called to vet me as an investor, says they average about one opportunity per month on their platform, with 34 deals closed to date.

CEO Casey Minshew says over the last five years they have been “Beta Testing” their thesis: That they can disrupt the closed, highly capital-intensive, and high fee world of oil & gas exploration, by giving access to smaller investors while reducing fees.

Minshew shared with me the results so far – involving 34 deals closed to date – as well as the direction he intends Energy Funders to go in the future.

Of 34 deals, 11 have been dry holes. Sixteen have produced appreciable oil and gas to date. Six of the deals, he considers, will be significant wins for investors. I did not independently verify his reported results, but those feel like results one should expect from high-risk investing, and therefore strike me as credible.

Minshew says that for this type of investment, small-dollar participants should split their money between a variety of projects, to lower their risk of failure on any one investment.

Unlike the past five years, however, Minshew explained that the next few years will look a little different in terms of project style. Until now, Energy Funders has mostly backed so-called “wildcat”-style drilling, in which funders inevitably drill dry holes, but hope to have enough big winners to compensate for losses.

Future capital raises on their Energy Funders will focus on lower-risk investing, through two methods. One is to create a portfolio approach to projects, allowing investors access to multiple drilling projects, for diversification purposes.

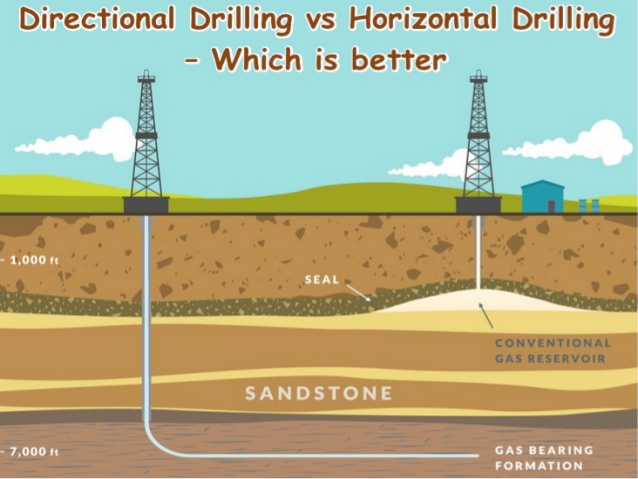

Their second risk-reducing plan is to open up access to “unconventional,” or horizontal drilling projects.

For those familiar with oil and gas extraction lingo, you’ll know what that means. For the rest of us, conventional means drilling a traditional, vertical, hole in the ground.

The way you lose money in conventional is if your vertical hole is dry, with insufficient oil or gas available for extraction.

Unconventional refers to horizontal drilling techniques and deep underground rock-formation smashing, known colloquially as fracking. The way you lose money in unconventional drilling is if the high cost of fracking exceeds the value of the oil and gas extracted – particularly if there’s too much gas and not enough oil. Success or failure is mostly a function of costs rather than dry holes. As an extremely general rule right now, gas is not profitable and oil is profitable, although markets obviously vary and will change in the future.

The project up on the site that I reviewed this week is one of their unconventional offerings, which has already been pumping oil and gas. The structure of that deal, as a result, offers less risk and less reward. But Minshew believes that’s increasingly what investors on their platform want.

I don’t mean to endorse Energy Funders as an investment vehicle in particular because, again, I know nothing about oil and gas investing. But the theory seems plausible to me that a larger market exists for lower-risk, lower-return investments in oil and gas, especially among the smaller-size investors that Energy Funder’s online portal will appeal to.

Since at least 2014, margins in oil and gas exploration have been thin. But like any good entrepreneur, Minshew finds a silver lining in tough market conditions for drillers. As he says,

“It is a capital-starved environment right now. [Oil and gas operators] are now willing to play ball with us. Which is to remove fees and reduce prices.” In addition to drilling risk, fees are largely what has hurt small investors. But Minshew believes “The more and more capital starved the industry, the more valuable we will be.”

In other words, he believes drillers will value the money Energy Funders can raise that much more, and that they can negotiate relatively strong terms for participants. That strikes me as a plausible theory.

I’ve written about and invested in, music royalties in the spirit of democratizing access to previously closed markets.

I’ve also written about, but not invested in, customer loyalty-based funding at Houston-based NextSeed which offers little-guy investing opportunities in startups like bars and restaurants. Energy Funders investments are also a kind of democratizing platform, but from a regulatory standpoint is only offered to accredited investors, who must meet a relatively high income or net worth threshold. While their investment minimums are very small – $5,000 – you do have to have some income or wealth to burn in order to participate.

Final note. I understand that to many readers the idea of investing in oil and gas – in the age of climate change – is akin to investing in cancer. I disagree, but ok.

A version of this ran in the San Antonio Express-News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts

My latest favorite investing idea – Music Royalties!

Crowd-Sourcing Restaurant and Bar businesses (to be posted shortly. SA-EN version here)

Post read (189) times.