Podcast: Play in new window | Download

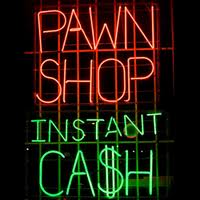

Where can you still find great customer service in financial services? The Pawn Shop!

Where can you still find great customer service in financial services? The Pawn Shop!

Michael: Hello, my name is Mike, and I used to be a banker.

Shirley: My name is Shirley, and I’m a long-time pawn-shop owner.

One of the themes of the Post-2008 Crisis world is how much people don’t like their banks.

I had a conversation with my friend Shirley who runs a financial services company whose practices are older than traditional banking – she runs a pawn shop.

While I was a banker, I never stepped inside a pawn shop – but I wanted to learn what their role is in the financial services business for the anti-banking crowd as well as the un-banked crowd. I found out that business is quite good in the niche her pawn shop fills. In addition she relayed an ironic an illustrative experience she had with her own business’ bank.

But first off, business has been really booming during the Great Recession.

Shirley: One thing that has really transformed our business is the high gold prices. But that’s one of the reasons we’ve seen such great success over the last few years, is those high gold prices.

A little gold ring that maybe at one time was worth thirty dollars is now worth a hundred dollars, so that really has transformed it for us. The other thing is the technology and the way that our business is run is really different than what it used to be, because we’re all run on the cloud. It’s very fast, and we can store a lot of information.

Shirley explained to me the advantage her pawn shop holds over traditional banks, including clarity of service, personal touch, and the ability to do small scale lending.

Michael: Do you think banks are missing something that they ought to be doing to get the customers or they just — they’re in a different sort of business, that they wouldn’t want your customers? It sounds like they can’t do what you can do.

Shirley: The banks — to do a loan like we do, it’s very labor intensive. We have to have storage space. We have to have customers entering all of the data of every single loan that’s being done. So for example we do almost a hundred loans a day, which the average loan being around ninety dollars, so it’s a very expensive loan to do in terms of labor. So certainly the banks can’t handle that. They wouldn’t have anywhere to put the items. You wouldn’t want one of your bank tellers lifting and moving and taking things through a warehouse. Definitely, we have a niche market. But I also think the banks are not interested in doing such short-term, small loans for that reason; it’s just too expensive.

Michael: I don’t know if you listened to a radio program of not that long ago, maybe six months ago, and I think it was a design program. But it basically talked about if you were an alien and you showed up and walked into a bank lobby where there’s no signage, there’s no menu, there’s no description of what they’re doing there, and you don’t know that they give loans. You don’t know what they do; it’s a very mysterious thing the way a traditional bank lobby is set up.

I’ve often thought about that. This radio show was about why in fact check cashing and payday lenders tell you, are a more inviting place for certain types of customers who don’t want to walk into a place where everybody is sitting behind a desk and there’s no menu, there’s no signage, there’s no description of what they do; whereas in contrast, your average check-cashing place, and there may be an analogy to what you all do at the pawnshop, it’s kind of clear. This is what we do and here’s how you engage in our financial service; whereas at the bank it’s totally unclear and off-putting, almost by either purposeful design of by mistaken design. This show is saying this is a terrible way for people to design it. I wonder if you have any comment about that, when you think about contrasting what you do versus what a bank does?

Shirley: That’s interesting. I haven’t really thought of that, but I think that’s exactly right. It is confusing when you go to a bank. It’s even confusing for somebody like me who’s been a traditional bank customer for a long time. If you have a question, even just about products they offer, you don’t really know who to ask. I had not thought of that before.

Yes, I think it’s much more clear in our industry. A person walks in and first of all they’re approached right away by an employee, at least in our store they are: “How can I help you?”

And the person says, “I need a loan.” “Okay, well let me help you with that.” It’s much easier, I think, than to walk into a place and you don’t know if you’re supposed to stand in line or do you go to the teller and say, “I need a loan”? Like “Oh, that’s not how it works.”

Michael: You can’t just walk up to the teller and say, “I want a loan, give me money.” They’ll just look at you like you’re an alien.

Shirley: Of course, and I hadn’t really thought about that, but that’s exactly right. Usually the person says, “I just need money to make this bill,” or “I just need enough money for gas until the end of the week.” So the customer usually comes in and tells you fairly specifically what it is that their needs are.

At a bank, of course you wouldn’t offer that service if a person came in and said, “I just need this small thing.” A bank can’t provide that. They’re not designed to provide that.

We are, more than any other industry, I think highly customer-service related because every time a person comes in the store they have to interact with an employee. That’s not true of most of the places that you go. Even when you shop at H.E.B, you don’t even have to see a teller anymore. You can scan your stuff and walk out. You never talk to anybody.

Shirley sees the pawn shop as a friendlier place to get financial services, but recently got a severe brush-off from her own bank. Her family has run this business for fifty years, but her big bank, (Ahem, Wells Farg0) neither valued her deposits, nor responded when she needed a loan to expand.

Shirley: Yes, and not only did they not necessarily want to lend to us, but they also didn’t want to take our deposits. I went through that a couple of years ago, when they wouldn’t even take our deposits. I said, “We don’t do check cashing, so really we just need a place to hold the money while we then turn it around and lend it to the customers.” They didn’t even want to serve us in that regard because there was such a negative connotation about the things that we do.

In my situation I often felt like the banks were — first of all they don’t really like to lend to us because we’re a pawnshop, just in general. I don’t think they necessarily, not because we compete with them, but either they throw us in there with the bail bondsman.

In fact, the unfortunate thing is these large banks they come into the community and they sort of give the impression they’re going to help the customers or they’re going to service the customers. But when it really comes down to it, they don’t have the authority to do anything. Then it really delays the process a lot because they have to send it to somebody in Tennessee to approve. Even a small loan, when I tried to buy a house in the neighborhood, it was a sixty-eight thousand dollar loan. It took ninety days and had to get approved from somewhere in Tennessee.

You’re right here across the street from me.

Michael: Right, “Come walk with me to what I’m buying.” “No we can’t do that. Tennessee has to weigh in here.”

In the end Shirley resolved her deposit and lending problem with a local bank, who actually took the time to understand her business.

Shirley: We did ultimately go to a local banker. We had tried the larger banks: Wells Fargo, BBVA/Compass and those where we had deposits for many years. But ultimately, it’s only the local bankers that do take the time to build a relationship to understand what we’re doing, and really to work in a way that you understand exactly how much this is going to cost, and what the fees are, and how this is going to be mutually beneficial for everybody. We did go through a local bank. Do you want me to say who the bank is?

Michael: No, it’s up to you. Or, whatever you want to say.

Shirley: Because, it’s has been, it’s actually been a very positive relationship once we got in touch with Broadway Bank, and they were the ones who really took the time. It’s been two years that we’ve been working on this project, and Broadway Bank has sort of held my hand along the way, reminding me to get the documents in, and ultimately we go with a small-business loan.

I’ve been saying for years that banks don’t really lend to small businesses – with the exception of real estate developers – because they’re not willing to take the time to understand individual businesses. They’re not normally willing to actually do what Shirley says her pawn shop does with her customers: figure out their need, and offer customized solutions. I was pleased to hear Shirley got something she’s been offering to her customers for fifty years.

Shirley: I think people are really still dying for human interaction, in most transactions. So, that’s where I think the pawn industry is still very customer-service oriented. It’s still very friendly. That’s what I would like for people to know.

Please Also See Interview Part II: Pawn Shop Owner Fights The Good Fight

Please also see subsequent Video: Pawn Shop owner turns Politico!

Post read (7680) times.