It pains me to write this[1], but Andrew Tobias’ hyperbolically titled[2] The Only Investment Guide You’ll EVER Need actually lives up to the name.

Tobias delivers solid personal financial advice, but in a playful tone.

He enlivens an entire chapter on saving money – the world’s dreariest subject – with anecdotes about his own fetishistic ways to scrimp.[3]

In the chapter about beginning to invest, Tobias delivers the punch-line early on: Trust No One, while offering fairly hilarious ways in which his younger, more gullible self, failed to head his own good advice.

In the stock-investing chapter, he hits the essential notes which readers of my earlier posts and reviews will know by now:

- The vast majority of individuals, could do a lot worse than just buying low-cost index mutual funds and never selling, as advocated by Nick Murray in Simple Wealth, Inevitable Wealth.

- Some money managers out of a large group will appear to ‘beat the market’ for an improbable-seeming time, but this type of result can be replicated with a coin toss experiment, as described by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in Fooled by Randomness.

- The intrinsic value of a stock derives from an enterprise’s ability to generate current and future cash flow, as Benjamin Graham’s Intelligent Investor explains.

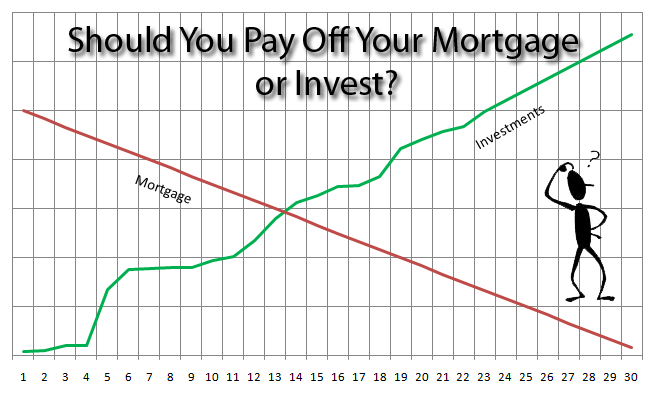

- Investing your first slug of savings through an IRA or 401K vehicle is a no-brainer. But even outside of tax-advantaged vehicles, the tax code heavily favors stock investing as a way to get rich.

Tobias made money early in his life – through best-selling books and then more significantly through best-selling personal finance software – so he managed to quickly accumulate a lifetime’s worth of successful and unsuccessful investment experience. He spins his unsuccessful experiences into memorable and hilarious ‘How-Not-to-Invest’ stories throughout the book.

But the best part of the book, Tobias saves for last. He comes up with an amazing way to teach kids about the power of compound interest, a personal obsession of mine.

Tobias suggests three versions of a Cookie Jar Experiment, which over a month can viscerally and intuitively teach the magic of compound interest to your kids.

- Version One. Offer your kid $1 on day one, and put it in the cookie jar. Offer to add 10% per day in interest growth on that original $1. Thereafter – Day 2: $1.10 in the jar, Day 3: $1.21, Day 4, $1.33. After a month you’ve got $17.45 in the jar, which shows how powerful 10% compounding can be, even if you begin with just $1. Tobias suggests you probably won’t continue the experiment to the end of Month 3 ($5,313) or Month 6 ($28 million) but of course, that’s up to you and your own resources. While ‘real life’ doesn’t let you compound that quickly on a daily basis, the experiment lets you demonstrate the amazing power of compound growth. [NOTE: I have since done this experiment with my oldest daughter, which I wrote about here. And then a follow-up post on the same topic here, as this allowance experiment is even better than I first realized.

- Version Two. Between your two kids, you offer the same deal, with a twist. If one of them is willing to skip the first three days of interest accrual, they can get something desirable like a chocolate bar. After they finish fighting over the chocolate, you run the experiment for two months. The kid who went hungry has $304, while the ‘lucky’ kid who got the chocolate only has $228 in the Cookie Jar at the end of 60 days. Lesson: Start saving early because it’s the earliest accruing period that matters the most.

- Version Three. Run the same experiment, but use the interest rate associated with many credit cards, like 20%. Start adding money to the $1 at a 20% growth rate and label this ‘Credit Card’ growth. On day 19 the ‘credit card’ account has grown to $32, versus the $6 that the original savings at 10% per day grew to. If you run the comparison all the way to day 35, the difference is $590 for the credit card account versus $28 for the ordinary 10% growth account. The key to this version is pointing out that some people scrimp and save and achieve some growth on their savings, while others pay huge amounts to credit card companies.

I taught a personal finance course last Spring, for bright college students, and I plan to do the same next Spring. One of my frustrations was with the textbook we used, a dry-as-dirt tome written by CPAs, seemingly for CPAs. My co-teacher and I ended up hardly ever referring to it, because how can you expect anyone to read such a thing?

Unless I can come up with something better real soon, the students will get assigned Tobias’ book. I think it’s all they need.[4]

Please see related post: All Bankers Anonymous Book Reviews in one place.

[1] It doesn’t actually pain me to say this. I use that turn of phrase to capture the sense of the Oscar Wilde aphorism “Every time a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies.” And Tobias is not a friend, but rather, I am jealous because I’m attempting to write a personal finance book, and Tobias has done such a good job with his.

[2] Tobias is a fan of the hyperbolic title, such as his excellent and funny My Vast Fortune, which I reviewed last month.

[3] He apparently carries Crystal Light powdered packets when he travels to save on beverages, buys canned goods by the pallet at Costco, rarely accelerates his car (to save on gas), checks his bank statements for errors every month, and has substituted cubic zirconium for diamonds in any jewelry purchases he ever made. In a related story, his net worth is above 99% of the people reading this right now.

[4] Until my book comes out, of course.

Post read (11335) times.