In the beginning of June, Social Security issued its annual Summary Report noting that the primary trust fund for paying reserves will run out in 2034. Twelve years.

Also, I was reading this past week a book by Peter Ferrera published in 1980 called Social Security: The Inherent Contradiction.

In 1980, Ferrera forecast the trust fund would run out in 2030, to which I have two reactions. First – that’s some amazingly accurate forecasting of a complex actuarial system over the span of 50 years! Well done, actuaries. Second – you Boomers have had at least 42 years to fix this. Like, what the heck? I am first eligible for Social Security retirement payments in that same year, 2034. Coincidence? I’m a Gen X kid, I’m used to this kind of treatment by now. It’s fine. Really. I’m fine.

More seriously, the real thing we should understand about the trust fund is this: It’s a useful fiction.

The trust fund isn’t particularly important.

Benefits get paid from current Social Security payroll taxes. The government is not actually investing our dollars. Technically, yes, a partial and temporary surplus of payroll taxes gets parked in low-interest Treasurys, but by no means is this the real source of our Social Security payments. It’s a pay-as-you-go system. Current workers pay for past workers.

In fact, understanding this is a fiction is the key to remaining calm about Social Security. Rather than panic, we should take comfort. The trust fund has never particularly mattered.

As Ferrera wrote in 1980, the idea itself of a trust fund is “a carefully contrived deception meant to mislead the public.”

Ferrera continued, “the entire purpose of this deception is to hide the welfare elements in the social security system and attempt to create the impression that social security is simply insurance without any welfare elements.” I agree.

Whenever I write about Social Security I receive panicked (or conversely, overly certain) emails asking – or informing – me about the Ponzi scheme underlying our biggest government program. This is neither true nor helpful. Ponzi schemes are not backed by mandatory payroll taxes. Social Security is.

I 100 percent do not worry about Social Security running out of money. It’s never been a true trust fund. Rather, it has always been primarily “pay as you go,” transferring tax dollars from current workers to current retirees.

Ferrara’s big idea from 1980 was that Social Security has two functions, insurance and welfare. Most Americans focus on the insurance aspect, in which they think they pay into the system during their working years and they think they get a return on investment back in retirement years. That insurance function is the fakery, and the trust fund a symbolic misdirection to assist in the legerdemain. The true function of Social Security is a welfare transfer.

Although I haven’t spoken with Ferrera, I’m certain we disagree on whether the welfare element is good. I think it is. He thinks it is not.

A not-sufficiently-understood aspect of Social Security benefits is that it deeply favors modest lifetime incomes over higher incomes, when it comes to benefits. This is partly accomplished through “bend points,” which mean Social Security pays based on 90 percent of an extremely modest lifetime salary, 32 percent of a medium lifetime salary, and only 15 percent of higher earnings. I’m simplifying the language around these “bend points,” but the idea is that the welfare benefit of Social Security favors the neediest. To match this focus on welfare, annual income above a certain amount ($147K in 2022) is not taxed for Social Security.

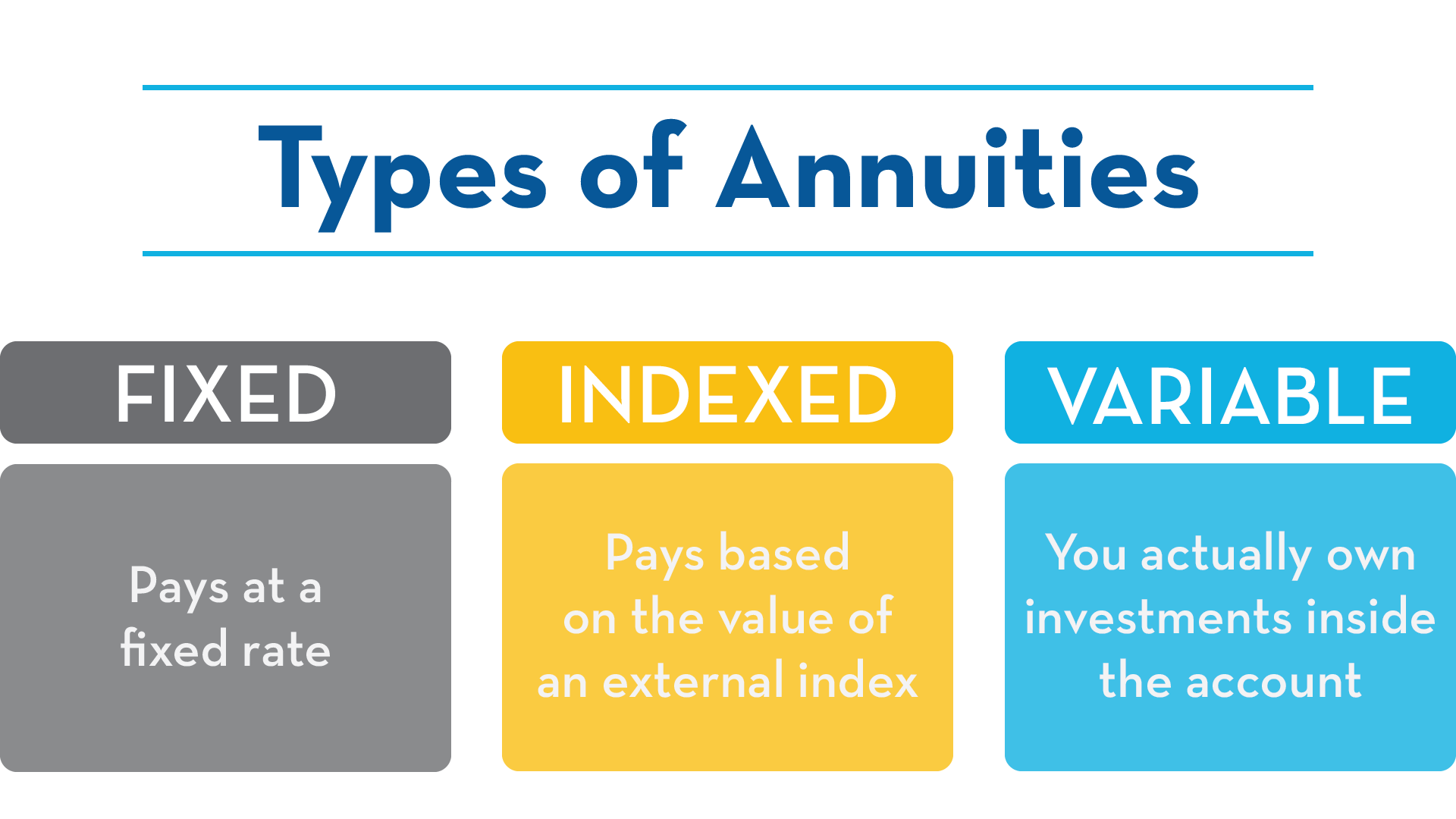

I am confident that in my own life, under reasonable assumptions, I would have achieved a greater net worth if I had never been taxed for Social Security and instead had invested those funds myself. The “welfare” part of Social Security will turn out to be a net loss for me, personally.

For most of my fellow citizens however, the welfare benefit of Social Security is a net gain. And that’s fine by me. This is socialism and should be understood as such.

I say that not as a diss of Social Security. In fact, ninety-six percent of adults polled consider Social Security an important government program. I mean to point out to a Texas readership with all of its preconceptions that a little bit of socialism can be pretty comfortable. Very popular and indeed, necessary. Not having elderly people die of starvation for example is a win in my book.

As for Social Security staying solvent, the real key is in understanding that this is solved with just a series of technocratic tax rule adjustments. The issue is not running out of money in the trust fund (again, the trust fund is largely irrelevant) but rather what small adjustments to delay and diminish benefits or boost taxes will be made to render the entire system solvent.

That was addressed in another 1980s throwback way this past week by former Senator Rudy Boschwitz (R-MN).

While serving in the Senate (1978 to 1990), Boschwitz had written a key memo in 1982 with proposals for shoring up the program. Yes, it is clear folks were worried back in the 80s about the issue.

Last week, in the Wall Street Journal, he listed the various ways to do it again.

Raise the “full” retirement age to beyond 67.

Raise the “early” retirement age to beyond 62.

Fiddle with the “bend points” so that payments are even less generous to higher earners.

Slow the rise in benefits by linking to a different, probably better, inflation index.

Slow the rise in benefits for higher earners.

Make inflation adjustments less frequently.

Tax Social Security income more heavily for higher earners.

Raise the payroll tax slightly to bring in more revenue.

This can all be phased in with many years’ lead time, in a boring, technocratic way. No need to panic. Which again is why I don’t worry about the so-called trust fund running out of money in 2034.

Big thanks to reader Steven Alexander who contributed data and analysis to Ferrera’s 1980 book, crunching numbers on computers back in the 1970s that accurately modeled things like return on investment and the end of the trust fund in the 2030s. I was reading his copy signed by the author.

A version of this ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts

My nerdy Social Security Spreadsheet, Part I

My nerdy Social Security Spreadsheet, Part 2

Post read (95) times.