I’ve done no general-population polling on the question “Do I have enough money set aside for retirement?” but informally I’d guess the US population would break down as follows:

1% – “Oh, yes, definitely,”

19% – “I hope so, but I’m not sure,”

80% – “LOL”

If you’re in the 99 percent uncertain category, as you move closer to retirement, you might find yourself thinking about the following question:

“What is a safe maximum annual withdrawal rate from my investment accounts that will still ensure I don’t run out of investment income, for the rest of my life?”

Economist Bill Bengen proposed an answer to this in the 1990s. For simplicity’s sake his conclusion remains the starting point for many advisors. I mention his conclusion below.

Then I want to explain the ways in which we can all be more nuanced about the Bengen rule in our own lives, since I don’t think it’s terribly useful, except maybe as a conversation-starter about retirement.

Bengen’s assumptions

For the purposes of research, Bengen assumed a 50/50 stock and bond allocation in an investment portfolio, and an annual increase in withdrawals from investments to match the rate of annual inflation.

Bengen’s sought to mathematically solve for a 100 percent success rate over a 30-year horizon. “Success” meant there was enough money over a span of 30 years to always withdraw the initial amount, plus an upward-increasing amount, to account for inflation, and not run out of money.

Bengen’s conclusion

His answer: start with a 4 percent withdrawal rate in Year One. Adjust annual withdrawals upward, in line with inflation.

The 100% success rate from his research meant that his rule took into account the historical experiences of crises like the Great Depression and the stagflation of the 1970s. By implication, Bengen’s rate could be relied upon in even the worst periods to come in the future.

Since then, traditional financial planners often start from the 4% rule, based on research that shows that client investment accounts will not hit zero within the 30-year time horizon. Because hard and fast rules provide simplicity, and because 100% certainly appeals to clients, I guess the 4% rule exists as an ok safe place to begin for everyone.

On the other hand, many factors make Bengen’s conclusion overly simplistic.

These factors include at least the following, which I’ll address one at a time

- The stock v. bond allocation mix

- The effect of retirement’s ‘early years’ on the success rate

- The skew of an overly-conservative 100 percent success

- Simplicity is too rigid

- Meaningful amounts

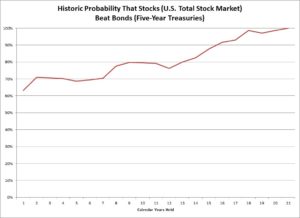

Stock versus Bond allocation

Research from Bengen found that increasing equity exposure above 50% increased the probability of “failure” under certain scenarios, although not much more risk was introduced up to a 75% allocation to equities. I would take it a step further and suggest that if a person wants to grow the most money before retirement – on a probabilistic basis – the portfolio has to skew much more heavily toward stocks. On a probabilistic basis – which Bengen’s rule disregards by solving for 100 percent success – a 50/50 stock and bond split remains too conservative even for most retirees.

The early years

Further research has shown that the first 15 years of a presumed 30-year retirement overwhelmingly determine whether the 4 percent initial withdrawal rate is too conservative. In essence, if the first 15 years of retirement are incredibly horrible ones – think 1929 or 1968 – then 4 percent will turn out to be the right rate. If they are historically average, however, the retiree will be able to safely ratchet withdrawal rates upwards, usually in a significant way. Most market conditions will render an initial 4 percent withdrawal rate overly cautious.

Overly conservative skew

As Mike Kitces points out, the overwhelming majority of retirees would end up with significant unspent money at the end of their life. Ninety percent of retirees would preserve their entire original investment amount if they started out spending only 4% a year. Fully two-thirds of retirees would actually end up with at least double their initial amount, by following Bengen’s 4% rule.

In response, some planners allow for ratcheting spending upwards, in response to positive markets, a more flexible spending plan.

Since I don’t believe children deserve free money, I think retirees should remain alert to the risk of ending up with too much money. If conditions are average, spend more freely than the initial 4 percent!

Meaningful income

Finally, the Bengen equation doesn’t consider the real-world issue of whether the income represents a meaningful amount of money or not.

What do I mean? I mean that a $100,000 retirement account will generate – at a 4% spend rate – $4,000 in income in the first year. That’s a nice amount of money but isn’t sufficient to maintain anybody’s lifestyle. The difference between a 3% spend rate and a 5% spend rate – in other words $3,000 the first year or $5,000 the first year – is not meaningful in the least.

So what is meaningful?

The bigger the portfolio, the more meaningful the issue will be. Sustainability of spending rate isn’t where one’s energy should go. Compiling the largest portfolio possible – through a combination of early and substantial contributions, and a large exposure to equities – should be the more important question.

That way, if you have a large portfolio by the time retirement arrives, the income from a withdrawal is meaningful.

A few final thoughts

Other ways to make your retirement portfolio more sustainable include lowering management costs – including advisor fees, transactions, and fund fees – lowering taxes, and diversifying.

These simple rules always hold true as well.

Please see related posts

Stocks vs. Bonds – The probabilistic answer

Post read (349) times.