How does a profane, hip-hop, hit of a show, and a chapter, dropped in the middle of a behemoth book on Alex Hamilton, by Ron Chernow capture the current zeitgeist, show us to treat our debt with sacred honor?

How does a profane, hip-hop, hit of a show, and a chapter, dropped in the middle of a behemoth book on Alex Hamilton, by Ron Chernow capture the current zeitgeist, show us to treat our debt with sacred honor?

Hamilton, the musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda, swept through my household this Summer like a hurricane, buffeting us as if we lived in a forgotten corner of the Caribbean. While the beautiful nerds of my household joyfully sing about the Revolutionary War, I tackled Ron Chernow’s biography Alexander Hamilton, upon which Miranda based his amazing show. A story Chernow tells about national debt illustrates Hamilton’s particular genius.

Serving President George Washington as the first Treasury Secretary of the United States, when the new country flirted with financial ruin, every action Alexander Hamilton took carried particular weight. He faced a terrible choice.

Soldiers in the Revolutionary War had received state IOUs in return for their military service. Years after the end of fighting with the British, many of these debts remained unpaid. In addition, different states had repaid debts to different degrees. Virginia was nearly debt-free for example, while Massachusetts still owed tremendous amounts to soldiers.

Some believed this new federal government would not, and could not, pay off its debts to soldiers. Chernow writes that these debts traded at fifteen cents on the dollar as former soldiers sold early, in part because they needed the money, and in part because full payment seemed doubtful. Speculators bought the debt at extreme discounts, hoping to make money if the young government could restructure the debt somehow. At that price, even a settlement of thirty cents on the dollar offered a financial windfall to debt-buyers.

What kind of deal would Hamilton, as Treasury Secretary, offer on the debt? Should he restructure it and offer a lesser amount? Should he seek a way to punish the speculators? Could he track down the former soldiers who had sold their IOUs, to compensate them, instead of the investors? Wait for it…

Let’s pause for a moment and really wallow in the awful optics and politics of Hamilton’s choice. Nobody deserved more respect than the first patriots who suffered and died under Washington, when his “ragtag volunteer army in need of a shower” defeated a global Superpower, in Miranda’s purposefully anachronistic phrasing. But most of the government debt issued to soldiers wasn’t owed to them anymore, but rather to buyers of their debt. These were some of the least sympathetic people. You know, Wall Street-type people.

The most powerful member of Congress, James Madison, and the Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, vehemently opposed rewarding the speculators. As Virginians, they also argued that consolidating the debts at the federal level would reward less prudent states at their state’s expense.

Picture, as well, Hamilton’s childhood as a near-destitute orphan in the Caribbean. He was not a natural friend of Wall Street. He’d served as a captain of an artillery company under fire in the Battery in Manhattan and the Battle of Kips Bay; he had personally led a bayonet charge on an entrenched position of Redcoats at Yorktown. Was Hamilton prepared to honor commitments that would enrich these greedy speculators who bought government debt at pennies on the dollar from his fellow soldiers? Wait for it…

He was, and he did. He consolidated the states’ debt into federal debt. On his first and second days after confirmation as Treasury Secretary in 1789, he took out fresh federal loans from the Bank of New York and The Bank of North America in Philadelphia.

Hamilton understood the value of communicating a policy of honoring one’s debts, a policy that strengthens the nation. “In nothing are appearances of greater moment than in whatever regards credit. Opinion is the soul of it and this is affected by appearances as well as realities,” he wrote in his 40,000-word Report on Public Credit, delivered to Congress in January, 1790.

He further set the precedent that the government does not interfere in private transactions of its public securities, even if the optics and politics would make it expedient to change terms, after the fact.

As Chernow reports, Hamilton reframed the moral issue into one of honoring private property and “security of transfer.” The soldiers were not as heroic as they seemed, nor the speculators as greedy. Investors after all, had risked their capital. The ex-soldiers, in turn, had shown little faith in the government. That the buyers of soldiers’ debt made extraordinary short-term fortunes was, in the far-seeing perspective of Hamilton, irrelevant to the more important work of establishing a solid financial footing for the country. Meanwhile, Madison and Jefferson fumed.

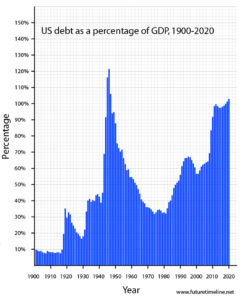

The United States has never defaulted on its debt. Not through the ruin of a burned capital in 1812, nor through a crippling Civil War, nor the World Wars and Depression of the Twentieth Century. Hamilton’s honoring of national debts – against all the political, fiscal and moral pressure of his day – bolstered us as a nation. It set us up for national prosperity.

As the fictional Jefferson of the Hamilton musical ruefully admits: “I’ll give him this: His financial system is a work of genius. I couldn’t undo it if I tried, and believe me, I tried.”

Or the fictional Madison: “He took our country from bankruptcy to prosperity. I hate to admit it, but he doesn’t get enough credit for all the credit he gave us.”

Contemporary debates

Shifting to 2016 for a moment, what would Senators Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren have done with Hamilton’s conundrum? Historical hindsight isn’t necessarily fair, but I’ve listened to their views on Wall Street, the industry where I previously worked, and which they consistently attack as a cesspool of greed, corruption, and speculation.

We also have GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump’s views on the record on our national debt. In stark contrast to Hamilton, Trump presented his approach in an interview with CNBC in May. He explained “I’ve borrowed knowing that you can pay back with discounts. [As President,] I would borrow knowing that if the economy crashed, you could make a deal.”

We also have GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump’s views on the record on our national debt. In stark contrast to Hamilton, Trump presented his approach in an interview with CNBC in May. He explained “I’ve borrowed knowing that you can pay back with discounts. [As President,] I would borrow knowing that if the economy crashed, you could make a deal.”

See, that’s not really how the bond market works. Hamilton had the foresight to know that once you default on debt – which is what “pay back with discounts” means – you set a precedent for how lenders view your credit in the future. I would even argue that once you even say that out loud – if anyone takes you seriously – you risk submarining your nation’s future ability to borrow.

Think about how lucky we are to be alive right now, with Hamilton on our side.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News.

Please see related post:

Trump: Sovereign Debt Genius

Post read (1122) times.